Vaping FAQs

.

Last updated 21 September 2024

.

Other useful resources

- Mendelsohn CP, Wodak A, Hall W, Borland R. Evidence review of nicotine vaping and recommendations for regulation in Australia. 23 October 2023

- Vaping myths and the facts. National Health Service, UK 2023

- Vaping to quit smoking. National Health Service. UK 2023

- Vaping Facts website. New Zealand Ministry of Health

- Addressing common myths about vaping. Action on Smoking and Health UK, 2023

- Vaping: a guide for health and social care professionals. UK National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training 2023

- Evidence summaries from Clive Bates on 1) Safety 2) Effectiveness 3) Youth use 4) Policy

The basics

Tobacco Harm Reduction is a strategy to reduce the harm for smokers who are unable or unwilling to quit. It involves replacing high-risk combustible tobacco products such as cigarettes with lower-risk, non-combustible nicotine alternatives, like vaping.

Video: Introduction to Tobacco Harm Reduction, March 2022 (10 mins)

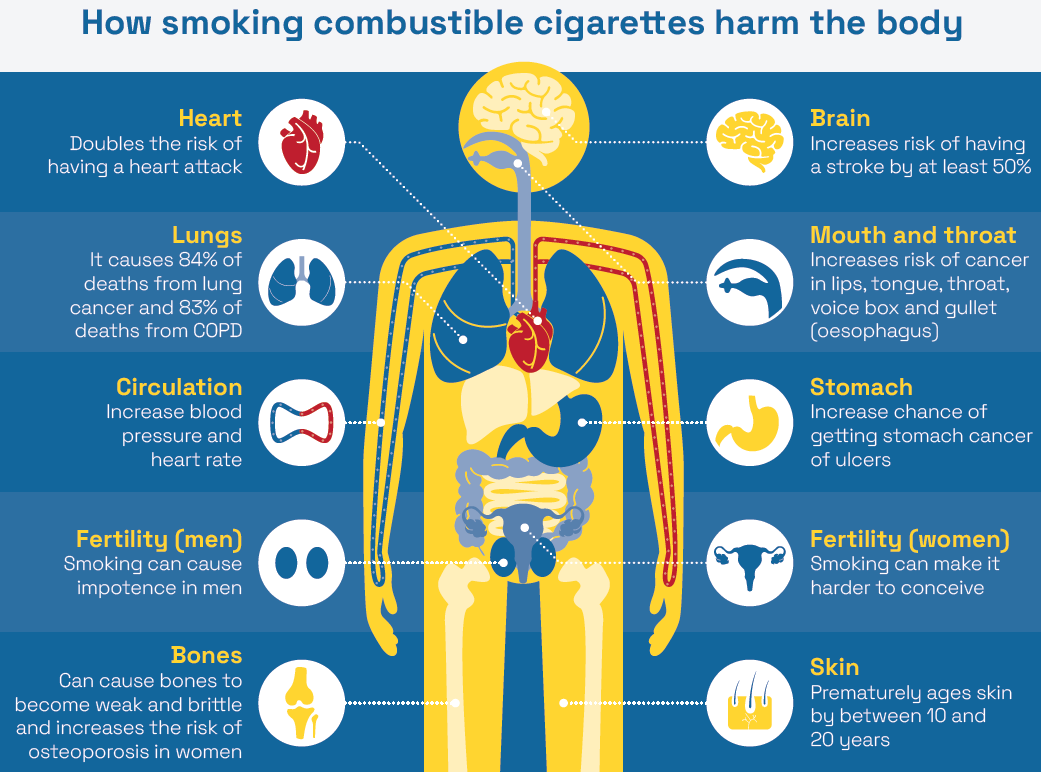

The aim of harm reduction is to reduce (not necessarily eliminate) the harms from smoking, in particular cancer, heart and lung disease. The aim is not to stop nicotine as nicotine causes little harm. Almost all the harm from smoking is from the thousands of toxic chemicals and carcinogens (cancer-causing chemicals) from burning tobacco. Reduced-risk products are not risk-free, but they are far safer than smoking.

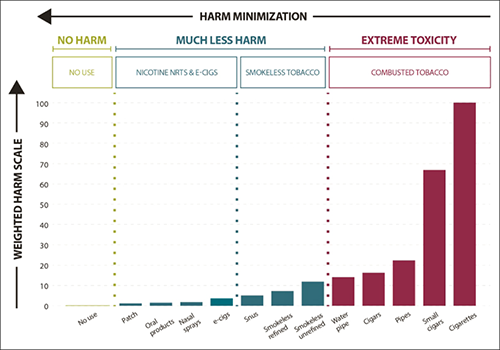

Reduced-risk nicotine products fall on a ‘continuum of risk’. They include vaping (using an e-cigarette), Swedish snus (small pouches of special tobacco placed under the upper lip), nicotine pouches (similar to snus but without tobacco) and heated tobacco products (which heat tobacco without burning it).

The aim of tobacco harm reduction is for nicotine users is to shift from deadly combustible products on the right of this diagram to safer products on the left.

The harm continuum of nicotine products (safer products on the left)

Safer nicotine products can supplement traditional tobacco control strategies which target complete quitting.

Tobacco harm reduction is no different to other harm reduction strategies which are generally very effective and widely accepted. These include methadone for heroin users, clean needle exchange programs and even car seat belts.

Tobacco harm reduction is one of the three pillars of Australia’s National Tobacco Strategy. One objective of the NTS is to “reduce harm associated with continuing use of tobacco and nicotine products” (p11).

Australia is legally obligated to support tobacco harm reduction as a signatory to the World Health Organisation Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. The FCTC provides an obligation on governments to not only allow reduced-risk products but actively promote them as part of implementing their tobacco control policies. Currently Australia is in breach of its international obligations as no harm reduction strategies are supported in practice.

Vaping is a less harmful alternative for adult smokers who are unable to quit smoking on their own or with other methods. Vaping delivers nicotine and mimics the familiar hand-to-mouth action, habit and sensations of smoking.

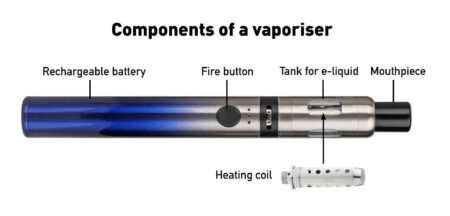

Nicotine vapes (e-cigarettes, vaporisers, ENDS) heat a liquid nicotine solution into an aerosol which is inhaled and exhaled as a visible mist. This is known as ‘vaping’.

All vapes consist of a battery (usually rechargeable), a tank or pod to hold the e-liquid and a coil or heating element to heat the liquid to create the vapour.

As there is no tobacco and no combustion, almost all the toxic chemicals in smoke are absent from vapour. Those that are still present are in far lower doses than in tobacco smoke.

Some smokers use vaping for a short time to quit tobacco smoking and then cease vaping. Others continue vaping long-term to prevent relapse to smoking. Some smokers experiment with vaping without intending to quit but then ‘accidentally’ quit.

Vapers take about 220 puffs per day on average [Yingst 2020 172; Aherrera 2020: 365; Dautzenberg 2015: 163; Kosmider 2019: 156; Dawkins 2013: 236; Robinson 2015: 225]. Some vapers takes vaping breaks of 10-12 puffs at a time. Others prefer to “graze” through the day, taking one or two puffs as needed. Either method is fine.

Inhalations from vaping are typically longer than when smoking: typically 3-4 seconds compared to 1-2 seconds.

Vaping should not be used by non-smokers including young people who don’t smoke.

Most people who take up vaping are smokers trying to reduce their risk of harm from smoking.

In Australia in 2023, current smokers aged 14+ gave the following reasons for taking up vaping (could select more than one response) according to the 2023 National Drug Strategy Household Survey: (Table 3.37)

- To quit smoking 36%

- To reduce smoking 28%

- They taste better 27%

- They are cheaper 25%

- To prevent relapse to smoking 22%

- Because they are less harmful 22%

- 42% of smokers said curiosity was a factor in their decision to try vaping

In Great Britain, ASH found similar results in 2023. The 4 main reasons for vaping were

- To quit smoking 31%

- To prevent relapse 17%

- Because they enjoy the experience 14%

- To save money compared to tobacco 11%

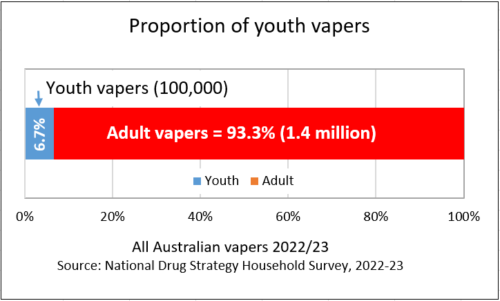

In the latest national survey, 1.5 million Australians, or 7% of the adult population (14+) vaped at least monthly and 3.5% vaped daily. In comparison, 1.8 million Australians, or 10.5%, adults smoke and 8.6% smoke daily. (National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022-23)

Another survey by Roy Morgan, reported in January 2024 that there were 1.7 million adult (18+) vapers in Australia, or 8.3% of the population. The number of people vaping had grown by 349% in 5 years.

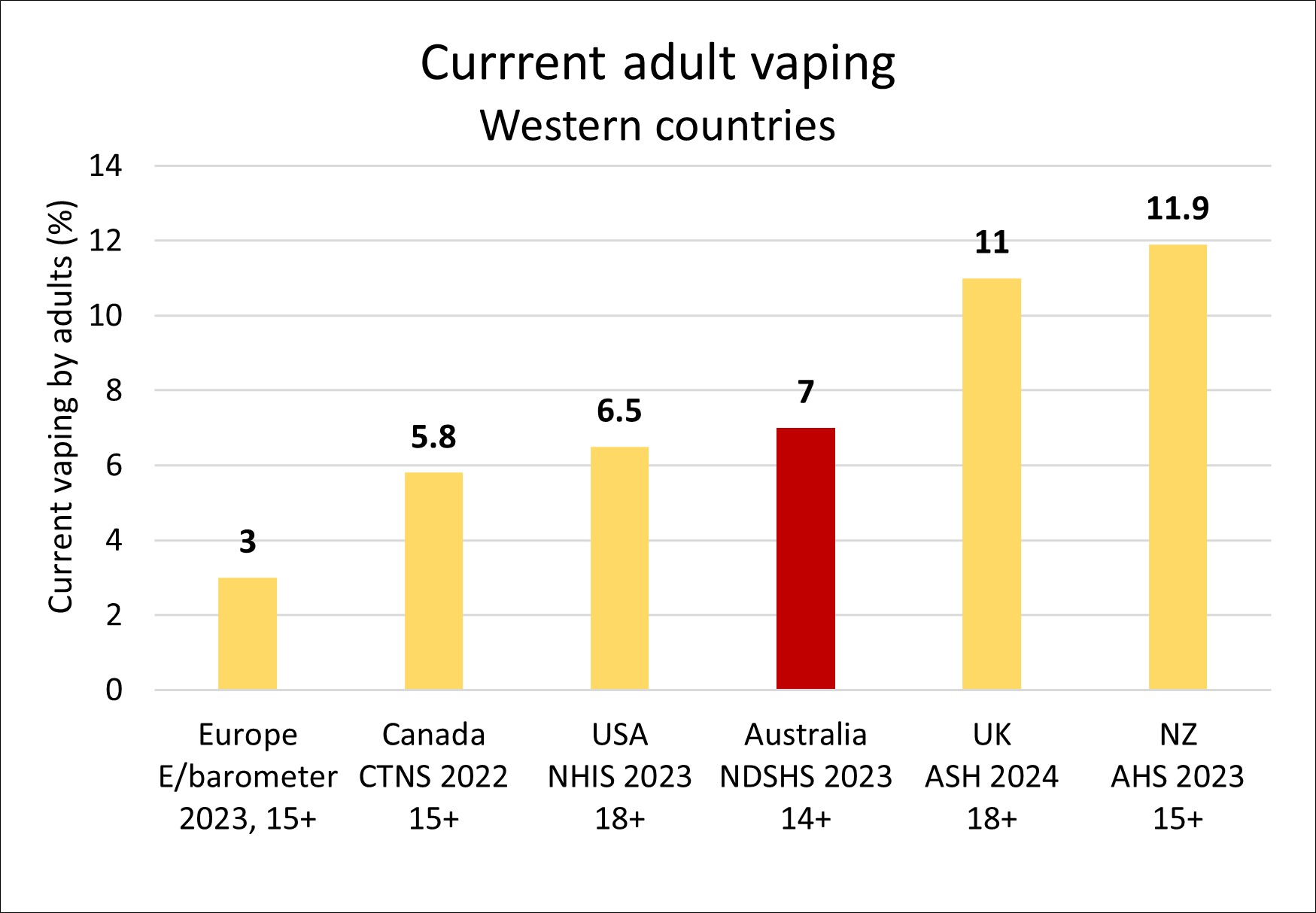

Comparison with other Western countries

Despite the harsh restrictions on vaping, Australia now has one of the highest adult vaping rates in the world.

- New Zealand, 11.9% (vaping monthly, 15+, 2023)

- Great Britain, 11% (current vaping, 18+, 2024)

- USA, 6.5% (vaping every day or some days, 18+, 2023)

- Canada, 5.8% (15+, past month, 2022)

- Europe, 3% (current vaping, 15+, 2023)

You can vape legally in Australia with a nicotine prescription from a doctor

Currently only 8% of Australian vapers have a nicotine prescription. The prescription model is a significant barrier for adult smokers wishing to legally access regulated nicotine vaping products to quit smoking or to reduce smoking-related harm.

Most doctors are reluctant to prescribe nicotine. As of April 2023, there were only 1963 doctors authorised to prescribe nicotine out of >100,000 doctors in Australia However only about 500 are publicly listed. The RACGP recommends that prescriptions are for 3 months only, although they can be up to 12 months supply.

The prescription model has led to a lucrative, thriving black market run by organised crime groups, selling unregulated, mislabelled, high nicotine content disposable vapes to adults and children.

There are severe penalties (up to $45,000 and up to two years jail) for using or possessing liquid nicotine unless it is prescribed by a doctor to help you quit or cut down smoking.

| State | Penalty | Prison Term | Legislation |

| ACT | $32,000 max or prison or both | 2 years | Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 2008, 4.1.3, 36 |

| Western Australia | $45,000 | Medicines and Poisons Act 2014, 2.16.2 and 115 | |

| Victoria | $1,817 | Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Regulations 2017 | |

| South Australia | $10,000 max | Controlled Substances Act 1984, 4.22 | |

| Northern Territory | $15,700 max or prison | 12 months | Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act , 2.2, Div 3, 44.2 |

| Queensland | $27,570 max | Medicines and Poisons Act 2019 , 2.1.1.34 | |

| New South Wales | $2,200 max or prison or both | 6 months | Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 1966, No 31, 16 |

| Tasmania | $8,650 or prison | Up to 2 years | Poisons Act 1971, Part 3, Division 1, Clause 36 |

State and Territory laws regulate issues such as sale, use in public places, age limits on sale, display and promotion of vapes.

The only legal way to purchase vapes is from an Australian pharmacy with a doctor’s prescription. Nicotine cannot be sold legally in Australia by vape shops, tobacconists or other retail outlets.

You will need to inform your doctor which product, brand and flavour (tobacco, mint or menthol) you require and find an Australian pharmacy that can provide it. The volume supplied per script is not limited, but is determined by the doctor.

However, there are only a very small number of community and online pharmacies which stock nicotine vaping products and most stock a very small range

There are additional standards for products supplied by pharmacies, including a full ingredient list, labelling, packaging regulations, safety warning statements and child-resistant containers. Nicotine concentrations up to 100mg/mL can be sold by pharmacies if approved by your doctor.

See below under “Regulation of Vaping” for more.

Safety and health

Vaping is not risk-free but it is far less harmful than smoking which kills up to two in three long-term users.

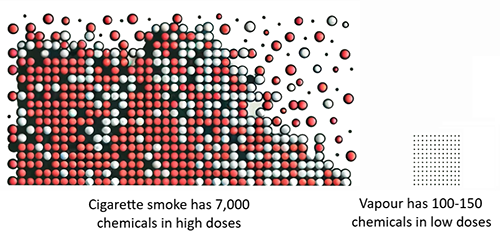

Almost all the harm from smoking is caused by the 7,000 chemicals in smoke (including 70 cancer-causing agents) released from burning tobacco. (Khouja 2024)

Source: No Smoke Less Harm 2024 (here)

In contrast, vapes heat a liquid into an aerosol, without tobacco, combustion or smoke. The toxic constituents in smoke are either absent in vapour or, if present, are mostly at levels significantly below 5% (mostly below 1%) of doses from smoking and far below safety limits for occupational exposure. and are at generally at much lower levels than in cigarette smoke. Studies have found on average around 100-150 chemicals in vapour from an individual device (eg Heywood review; Sleiman: Margham).

A comprehensive systematic review in 2022 for England’s Office for Health Improvements and Disparities concluded:

“Vaping poses only a small fraction of the risks of smoking and is ‘at least 95% less harmful’ than smoking”

According to the UK Royal College of Physicians report in 2024:

“Vaping exposes vapers to a far narrower range of toxins than does smoking cigarettes, and levels of toxins absorbed from vaping are generally low. It is therefore likely that vaping poses only a small fraction of the risk of smoking”

A review by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in 2018 concluded:

“While e-cigarettes are not without health risks, they are likely to be far less harmful than combustible tobacco cigarettes”

The advice of the United Kingdom National Health Service is:

“Nicotine vaping is not risk-free, but it is substantially less harmful than smoking”

According to the UK National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training:

“Anyone who switches from smoking to vaping is instantly improving their current and future health”

Numerous studies have also shown substantial reductions in biomarkers of exposure (toxins in the blood, saliva or urine of users) and biomarkers of potential harm (signs of damage to the body) in tobacco smokers who have switched to vaping.

Individuals who use nicotine vapes to quit smoking completely will gain significant health benefits. Clinical trials and surveys of smokers who completely switched to e-cigarettes have shown improvements in asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), blood pressure, muco-ciliary clearance, respiratory infections, lung function, respiratory symptoms, cardiovascular markers and gum disease.

Based on the level of carcinogens and their potency, the lifetime cancer risk from vaping has been estimated as less than 0.5% of the risk from smoking.

For a review of the evidence on vaping safety please watch my presentation to the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre at the University of New South Wales [17 February 2022]:

A written summary of the presentation is also available here.

Common side-effects

The side-effects most often reported from vaping are throat or mouth irritation, headache, cough and feeling sick. According to the Cochrane review the side-effects “appeared similar to those people experience when using NRT” (up to 2 years follow-up). These tend to reduce over time as people continue vaping. Another review of 18 studies did not find a difference in the rate of side effects between vaping nicotine and nicotine replacement products.

Is vaping safe?

Much of the debate about vaping is framed in terms of whether vaping is safe. This is the wrong question and sets a high bar that we do not apply to other behaviours, such as drinking alcohol, eating fast food, or playing sport.

Nothing is completely safe. We all take risks every day, weighing the risks against the benefits. We decide if the risks are within our ‘risk appetite’ for the benefits we get.

Nicotine products fall on a continuum of risk with the most harmful products being combusted tobacco. E-cigarettes containing nicotine are at the lower end of the scale and cause little harm in comparison.

Nicotine risk continuum (adapted from Abrams 2020)

Reducing your risk

If you vape, you can reduce your risk further:

1. Avoid vaping at excessively high temperatures to reduce the production of toxic byproducts. (PHE 2018)

2. Vape with higher concentrations of nicotine. If the nicotine concentration is too low, you will compensate by puffing more and will inhale more toxicants. (Dawkins 2016)

3. Use high quality, reputable products to reduce exposure to contaminants (remember EVALI). (Mendelsohn 2022)

4. Unflavoured vapes avoid exposure to flavouring chemicals whose long-term effects are unknown.

5. Cease vaping when you are confident you won’t relapse to smoking.

Yes. This estimate is based on comprehensive, independent reviews of the scientific evidence.

The most rigorous and comprehensive systematic review of the health effects of vaping nicotine commissioned by the England government (Office of Health Information and Disparities) in 2022 concluded

Vaping is “at least 95% less harmful” than smoking, based on their finding that “vaping poses only a small fraction of the risks of smoking”

The same conclusion was reached by both Public Health England and the UK Royal College of Physicians, who put it this way:

“Although it is not possible to precisely quantify the long-term health risks associated with e-cigarettes, the available data suggest that they are unlikely to exceed 5% of those associated with smoked tobacco products, and may well be substantially lower than this figure”

Of course, the exact figure doesn’t really matter, but saying the risk of vaping is probably less than 5% of smoking helps to communicate a ballpark for the level of risk so smokers can make an informed choice. Just saying vaping is ‘less harmful’ is too vague. That could be 30%, 60%, or maybe even 99% less harmful.

The ”95% safer” figure is based on the following evidence

- Most of the harmful toxicants in smoke are completely absent from vapour. Those that are present are at much lower concentrations, mostly at levels below 1% of what they are in smoke. If the toxins are much lower, the health risks will be much lower.

- When smokers switch to vaping, levels of toxicants and carcinogens (biomarkers of exposure) measured in the blood, saliva and urine are substantially lower and for many toxins are the same as for a non-smoker.

- Smokers who switch to vaping also have lower levels of biomarkers of potential harm, ie changes in the body from smoking that are associated with disease eg oxidative stress, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction

- There are substantial health improvements in smokers who switch to vaping. Risk of a heart attack reduces, the blood pressure falls, asthma and COPD (emphysema) improve and smokers often say they just feel a lot better after switching.

- The risk of cancer from vaping has been independently estimated to be <0.5% of the risk from smoking.

- After 15 years of vaping nicotine in dozens of countries, there has not been one death. Serious health effects are extremely rare.

Like all new products, the long-term risk of using e-cigarettes will not be fully understood for some years. However it is highly likely vaping will be considerably less harmful than smoking. [OHID UK, NASEM, COT UK, PHE, NZMoH, Health Canada]

Vaping is not risk-free. However, the risk must be compared to the alternative, i.e., continuing to smoke. Based on scientific principles and what we already know (which is substantial), the Royal College of Physicians estimates the long-term risk is likely to be no more than 5% of the risk of smoking.

According to Professor Ann McNeil, author of the UK government commissioned reviews on the harms of vaping,

“It is wrong to say we have no idea what the future risks from vaping will be. On the contrary levels of exposure to cancer-causing and other toxicants are drastically lower in people who vape compared with those who smoke, which indicates that any risks to health are likely to be a fraction of those posed by smoking”

In the absence of long-term data, modelling studies are a well-accepted way of estimating the population impact of an intervention. Numerous modelling studies estimate that vaping nicotine has a significant net public health benefit under all realistic assumptions and would do so even if it generated 20% of the harm of smoking.

Given that it appears to take in the vicinity of 20 years or more of daily smoking to increase risk of premature mortality, taking in a fraction of that amount over similar periods is likely far less likely to produce adverse effects.

There were an estimated 82 million people vaping in dozens of countries in 2021. Some ex-smokers have used vapes for over a decade, and to date, reports of serious adverse effects are very rare.

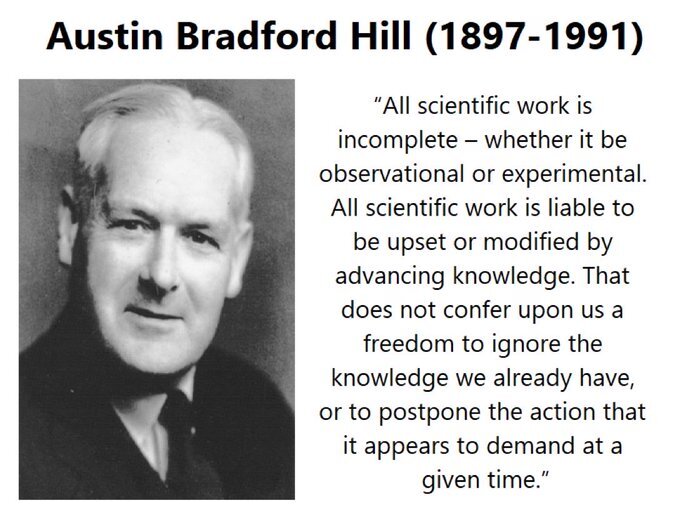

The requirement for policy to wait decades for evidence of long-term safety is not applied to other medical or consumer product, for example COVID vaccines. We normally base decisions on the current evidence and modelling studies. Nicotine vaping devices have been used by millions of consumers for far longer than many approved medicines or consumer products.

There is a theoretical possibility that long-term vaping may increase the risks of lung cancer, emphysema, cardiovascular and other smoking-related diseases. However, these risks are likely to be significantly lower than the risks of smoking and low in absolute terms.

Like all new medicines and treatments, post-market surveillance of vaping (ongoing monitoring after going on the market) should continue to monitor safety and detect any new side-effects. As with any new product, it is possible that some harms may emerge over time.

If cigarettes were invented today, we would know very quickly that they were very, very harmful.

We know much more today about chemistry, toxicology, physiology and the causes of disease than when cigarettes were introduced over a century ago. We have a much greater understanding of the toxic effects of most chemicals and can assess them against occupational and environmental health and safety standards. The scientific method, analytical techniques and equipment are also far superior to that available in the past.

This claim is a tactic by vaping opponents to cast doubt on the safety of vaping. However, extensive and rigorous research of vapes has concluded beyond reasonable doubt that vapes carry only a small fraction of the risk of cigarettes and are a far safer substitute for smoking.

The requirement to prove long-term safety when a product is launched is not applied to any other product. Regulators require safety data but do not ask for decades of epidemiological evidence before approving a new medicine. The COVID vaccine was approved within a few months. Like vaping, delaying it would inevitably result in many preventable deaths from COVID and is not justified. Similarly, delays in making vapes available would lead to huge numbers of unnecessary deaths from smoking.

Post-market surveillance is available to identify any unexpected adverse effects that may arise.

Switching from smoking to vaping dramatically reduces your risk of cancer. And, in spite of what many people think, nicotine does NOT cause cancer.

Presentation on the relative risk of cancer from smoking and vaping,

Medical Grand Rounds, Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney, 22 November 2023

The overall cancer risk from vaping nicotine is estimated to be <0.5% (less than one in two hundred) of the risk from smoking. The lung cancer risk has been estimated to be 50,000 times less than from cigarette smoking. The lifetime lung cancer risk fromsecond-hand vapouris estimated to be 50,000 times less than from second-hand smoke.

This is because the cancer-causing chemicals (carcinogens) in tobacco smoke are dramatically reduced in vapour. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the US Surgeon General, the main cancer-causing toxins in tobacco smoke are:

- polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- tobacco-specific n-nitrosamines

- volatile organic compounds (Benzene; 1,3-butadiene)

- aldehydes (formaldehyde, acetaldehyde)

- aromatic amines (2-naphthylamine; 4-aminobiphenyl

- ethylene oxide

When smokers switch to vaping all of these carcinogens are substantially reduced, when measured in the body fluids. In many cases they are at the same level as a non-smoker. Ensuring you do not vape at an excessively high temperature reduces the production of toxicants and the health risk further. (PHE 2018)

Contrary to popular belief, nicotine itself does not cause cancer. (International Agency for Research on Cancer; USDHHS 2010)

Expert opinion

Vaping is strongly supported by the leading UK cancer charity Cancer Research UK, which states:

“There is no good evidence that vaping causes cancer. Because vaping is far less harmful than smoking, your health could benefit from switching from smoking to vaping. And you will reduce your risk of getting cancer”

A review by the US National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine concluded:

“There is little evidence that e-cigarettes pose significant cancer risk”

UK National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training

“The cancer risk for people who vape is considerably lower than for those who smoke”

Cancer from smoking

Smoking is responsible for 21% of the total cancer burden in Australia and 65% of this is due to lung cancer. Smoking is predicted to cause over 250,000 cancer deaths in Australia from 2020 to 2044.

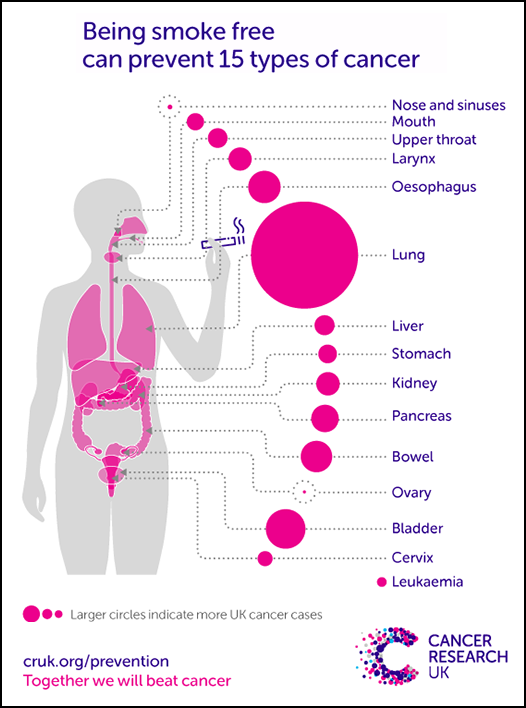

Tobacco smoke contains 69 known carcinogens and causes at least 15 types of cancer.

Further reading: Switching from smoking to vaping dramatically reduces cancer risk

Unlike secondhand smoke, there is no evidence that passive vaping is harmful to bystanders.

According to expert health organisations:

- Public Health England’s review in 2018. “To date there have been no identified health risks of passive vaping to bystanders”

- Health Canada in 2023. “The risks [from second-hand vapour] are expected to be much lower compared to second-hand smoke from a tobacco product. This is because second-hand aerosol from vaping contains significantly fewer chemicals than cigarette smoke.”

- UK National Health Service, 2023. “There is no evidence so far that vaping is harmful to people around you”

Chemical exposure. Research shows that vaping releases extremely low levels of chemicals into the surrounding air which pose very little risk to health. In one study, a range of of toxins were tested in bystanders None were increased except for IL-1B levels (a sign of inflammation), possibly due to secondhand exposure. Bystanders are exposed to low levels of chemicals because:

- The person vaping absorbs over 90% of the inhaled aerosol – less than 10% of the chemicals are exhaled

- About 85% of secondhand smoke comes from sidestream smoke released from the burning tip of the cigarette, but there is no sidestream vapour released from vaping products

- The liquid aerosol droplets from vapour evaporate and disperse in seconds, much more quickly than the solid particles in smoke, reducing risk further.

Nicotine levels in the air from vaping are also very low. A 2024 real-world US study found that children absorbed 16% of the nicotine from indoor vaping compared to smoking. This confirmed the finding of an earlier study which found that exposure to nicotine in children was 12% compared to tobacco smoke. Another study found that, nicotine levels from secondhand vapour were marginally raised, but were unlikely to cause dependence.

Cancer risk. Based on the carcinogens in second-hand vapour and the estimated doses, the cancer risk for passive smokers was estimated to be five orders of magnitude (50,000x) greater than for passive vapers.

Nicotine is a relatively benign drug. Although it causes dependence, it presents very little risk to the user and even has some significant beneficial effects.

Because of its association with smoking, many people incorrectly believe it is the harmful ingredient in tobacco smoke. However, the vast majority of harm from smoking comes from tar, carbon monoxide, toxic gases and solid particles released by burning tobacco, not from the nicotine.

Expert assessment of nicotine risks

- UK Royal College of Physicians 2024, “There is little evidence of a long-term harmful physiological effect of nicotine” and “most of the harm from smoking is caused by [these] products of combustion” (page 8).

- The Royal Society for Public Health has concluded that nicotine is a mild recreational stimulant and is “no more harmful to health than caffeine”

- Public Health England “nicotine use per se represents minimal risk of serious harm to physical health and that its addictiveness depends on how it is administered”

- UK National Health Service, “Although nicotine is addictive, it is relatively harmless to health. Nicotine itself does not cause cancer, lung disease, heart disease or stroke”

- Professor Neal Benowitz: “Nicotine plays a minor role, if any, in causing smoking-induced diseases”

- 15 past presidents of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (SRNT): “Nicotine is the chemical in tobacco that fosters addiction. However, toxic constituents other than nicotine, predominantly in smoked tobacco, produce the disease resulting from chronic tobacco use”

Nicotine does not cause cancer

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) 2012: “nicotine is not carcinogenic” (p139)

- US Department of Health and Human Services 2014: There is insufficient data to conclude that nicotine causes or contributes to cancer in humans” (Ch5, p116)

- Royal College of Physicians 2016: “nicotine alone is not carcinogenic” (p58)

- US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) 2018: “there is no human evidence to support the hypothesis that nicotine is a human carcinogen” (p4-17)

- Cancer Research UK 2023: “nicotine does not cause cancer”

- Health Canada 2023: “nicotine itself is not known to cause cancer”

Health effects of nicotine

Nicotine has mild effects such as temporarily increasing the pulse and blood pressure and narrowing the blood vessels. It can impair wound healing and raise blood glucose levels.

Nicotine does not cause lung disease or stroke, and only has a minor role in cardiovascular health (Benowitz: Kim).

Long-term use of nicotine is regarded as low-risk, based on decades of use of Swedish snus which releases high levels of nicotine, and nicotine replacement therapy. Nicotine in nicotine replacement therapies such as nicotine patches and gum is on the WHO List of Essential Medicines. Nicotine is approved for use as a medicine in Australia from the age of twelve.

Beneficial effects of nicotine

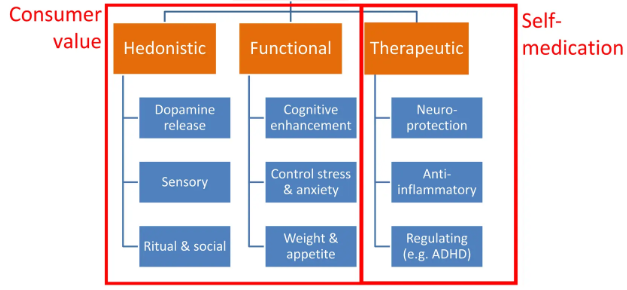

Nicotine has a range of benefits, including hedonistic (pleasure), functional and therapeutic effects:

Source: Clive Bates, ECig Summit 2023

- Nicotine improves attention, working memory and cognitive function (more here)

- It also creates pleasure, reduces anxiety and relieves depression

- Therapeutic effects on Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, ulcerative colitis and attention deficit disorder

- Weight control

- Pain relief

Many people regard nicotine (when delivered with minimal harm) as a socially acceptable recreational stimulant, like caffeine and alcohol.

A word on the definition of ‘addiction’

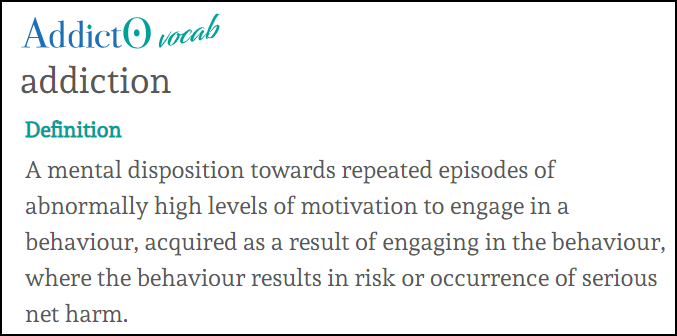

The urge to vape is not strictly characterised as “addiction”. According to Addiction Ontology, the definition of addiction is a compulsion to engage in a behaviour known to cause serious net harm.

Nicotine has only minor health effects and the urge to vape is best described as dependence. Dependence means having the urge to use a drug to avoid physical symptoms of withdrawal when it is ceased.

The dependence of nicotine alone is also overrated. There are other ingredients in tobacco smoke which make nicotine more habit-forming (monoamine oxidase inhibitors). Cigarettes also deliver nicotine very quickly which increases its dependence potential.

However, outside of tobacco smoke, nicotine is far less dependence-forming. For example, nicotine gum and patches have very low risk of dependence but are used long-term by some ex-smokers to prevent relapse. The behavioural, sensory and social aspects of smoking also enhance dependence.

A double standard: nicotine and caffeine

Nicotine dependence is often met with outrage and alarm, while caffeine dependence is largely dismissed as a minor concern. Caffeine dependence is generally accepted as a small price to pay for the enjoyment and perceived benefits of its use, with little of the stigma attached to nicotine.

Like nicotine, caffeine has stimulant and cardiovascular effects and similar withdrawal symptoms to nicotine. (Denaro 1991) People have died from overdoses of caffeine (Capelletti 2018)) as well as nicotine. (Maessen 2020)

Caffeine is the most widely used psychoactive drug in the world. Many regular coffee drinkers experience withdrawal symptoms strikingly similar to those of nicotine withdrawal when they miss their daily dose. It’s common to hear people say they “can’t start the day” without a coffee. Neither drugs should be used by young people.

There is no evidence that nicotine vaping causes seizures. The fact that a seizure occurred while vaping or soon after, does not prove that vaping was the cause.

A study in 2019 found that 114 vapers had reported a seizure. However this observational study could not indicate whether vaping had caused the seizures. In the US, 35 cases of seizures ‘associated with vaping’ were reported to the FDA from 2010-2019.

Soon after, the FDA acknowledged that “A causal relationship between e-cigarette use and seizure has not been established“. Some of these episodes were in people with epilepsy, others caused by illicit drug use.

Further, a review of vaping and seizures in 2020 by Professor Neal Benowitz:

Did “not consider seizures to be a potential adverse effect that should influence the decision of an adult smoker to use e-cigarettes to try to stop smoking conventional cigarettes”

Nevertheless, claims that vaping causes seizures are breathlessly reported by the media. It is also claimed without evidence in Australian government-commissioned reports eg here and here.

Association or causation?

Both vaping and seizures are common

- About 1.6 million adult Australians and many young people are currently vaping.

- At least 150,000 Australians are estimated to have seizures from epilepsy. Other causes are medications, drug and alcohol use, a head injury, a brain tumour or brain infection.

As a result, it is likely that some people who vape will have a seizure from time to time. However, this is an association of two behaviours, and is not causal.

The NHMRC incorrectly claims that there is “high certainty” evidence that vaping leads to seizures. This claim was subsequently debunked by 11 leading international experts in a critique in Addiction:

“A small number of case studies have reported seizures in people using nicotine e-cigarettes, but these cases do not establish causation and hence do not qualify as ‘high-certainty’ evidence. Many of these cases had a pre-existing seizure disorder, and some had used other drugs. If nicotine e-cigarette use was a cause of seizures, an association between cigarette smoking and seizures would also be expected—but none has been reported”

Severe nicotine poisoning

Claims of seizures from vaping nicotine may be confused with seizures from severe nicotine poisoning. A nicotine overdose from ingesting nicotine liquid can cause seizures and this may have led some people to think that nicotine vaping may also be implicated.

Further reading: Benowitz N. Seizures after vaping nicotine in youth: A canary or red herring J Adol Health 2019

Research has not identified any serious harms to the lungs from vaping nicotine in the short-medium term. An expert review concluded that vaping nicotine is unlikely to raise any significant concerns for lung health. (Polosa)

Improved lung health after switching from smoking

There is good evidence that lung health improves in smokers who switch to vaping. Breathing, cough and reduced phlegm improve (Hajek; Shiffman) and there are short- to medium-term improvements in asthma (Polosa), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (emphysema) at 5-year follow up (Polosa), muco-ciliary (phlegm) clearance (Polosa), respiratory infections (Miler; Lucchiari) and lung function (Cibella). These changes are likely to persist over the longer term. Furthermore, the lung cancer risk from vaping is estimated to be 50,000 times less than from smoking. (Scungio)

Harm from vaping by non-smokers

Longitudinal studies in people who have never smoked have not found significant harmful effects so far on lung health.

- Non-smokers may get transient throat irritation, cough or wheeze. However, there is no evidence to suggest that this may lead to clinically significant harm. (Polosa)

- A 2-year longitudinal study in 2024 by Karey found “no significant association … between e-cigarette use [in never-smokers] and important respiratory symptoms”. In a similar study, Reddy also found no increase in respiratory symptoms after 12 months in never-smokers who vaped.

- A 2-year study by Sargent found that “no significant association was detected between e-cigarette use and important respiratory symptoms”, concluding that respiratory symptoms were “largely not significantly different from never or former tobacco users”.

- Polosa studied nine daily vapers who had never smoked and found no evidence of lung damage after 3.5 years. There were no respiratory symptoms, no changes in lung function, markers of inflammation or change in lung scans.

- Kenkel found no evidence of respiratory disease in a longitudinal study over 3-years of 12 never-smokers who vaped.

- Sanchez-Romero found that exclusive vaping in never-smokers did not increase the risk of wheezing in a national study over 5 years in the US. However an increase in wheezing was reported in smokers.

- Berlowitz reported a reduction in cough but found an increase in wheezing in non-smoking vapers. The significance of the results has been questioned because of the low numbers, reliability of self-reports, possible other explanations and uncertain clinical significance.

However, larger, longer studies are needed before firm conclusions can be drawn. There may be some risk for heavy, long-term vapers.

Contrary to media reports, vaping nicotine does not cause the serious lung disease EVALI (Mendelsohn), “popcorn lung” (CRUK) or spontaneous pneumothorax.

This review does not include cross-sectional studies which cannot determine causation.

See below for more about the effects of vaping in young people.

What about laboratory studies?

Cell and animal studies have found that vaping can cause oxidative stress, inflammatory changes, reduced cell viability (survival) and DNA damage, although these changes are much less than from smoking. (Wang; Caruso; Emma) Findings from cell and animal studies are often not a reliable guide to human effects and should be treated with caution. (Bracken)

Conclusion

Vaping is not risk-free and it is not recommended for non-smokers. However, vaping is clearly far less harmful to the lungs than smoking because of the substantial reduction in exposure to toxins. The research so far has not found significant concerns to the lungs from short-medium term use.

Nevertheless, it is possible that respiratory harm from vaping may become apparent from many years of use, especially in long-term and heavy users, and continued investigation is needed.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Professor Riccardo Polosa for reviewing this analysis.

No. This condition was not caused by nicotine vaping.

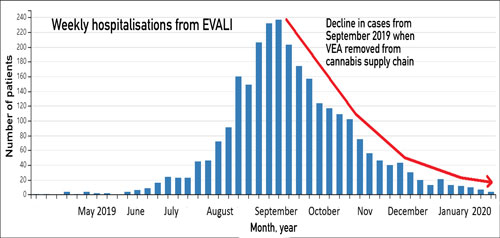

In 2019, there was an outbreak of a serious lung injury EVALI (E-cigarette, or Vaping, product use-Associated Lung Injury) in the US in people who had recently vaped. This condition has now been clearly associated with vaping black-market cannabis (THC) oils contaminated with vitamin E acetate (VEA), purchased from street dealers.

Not a single case has been linked to commercial nicotine vaping to stop or reduce smoking. VEA cannot be dissolved in nicotine e-liquid and has never been detected in nicotine e-liquid. Noo other potential cause in nicotine vapes has been identified.

When VEA was removed from the illicit supply chain, EVALI disappeared in early 2020. No further cases have been reported in the US despite the continuing widespread use of nicotine vaping and no significant e-cigarette product changes.

Some fourteen percent of cases denied using THC vapes and some commentators have incorrectly claimed that nicotine vapes must have been the cause. However some of those who denied using THC were later found to have done so after family interviews or testing. Also, THC was illegal in many states at the time. False denials were more common in states where THC was illegal.

The death of an Australian man in 2021 was incorrectly attributed to EVALI. The man had been a heavy smoker for 40 years and switched to vaping 10 years before his death. It is far more likely that the man died from progressive lung damage caused by 40 years of heavy smoking.

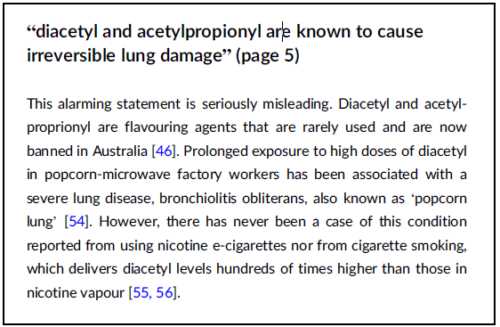

No. There is no evidence that vaping nicotine causes this condition and there has never been a single case linked to vaping.

No. There is no evidence that vaping nicotine causes this condition and there has never been a single case linked to vaping.

‘Popcorn lung’ (bronchiolitis obliterans) is a serious, but rare lung disease first detected in popcorn factory workers. It was linked to very high levels of ‘diacetyl’ which is used to create a buttery flavour.

Some earlier e-liquids contained diacetyl, however the levels found in vapour were hundreds of times lower than in cigarette smoke and there has never been a case of bronchiolitis obliterans due to smoking or vaping. Diacetyl is now rarely used and is banned in Australia in e-liquids.

According to leading health organisations

- Health Canada: “Vaping is not known to cause Popcorn lung”

- Cancer Research UK: “E-cigarettes don’t cause the lung condition known as popcorn lung. There have been no confirmed cases of popcorn lung reported in people who use e-cigarettes”

- Public Health England: Vaping does not cause popcorn lung

- UK National Health Service. “Vaping does not cause ‘popcorn lung’, the common name for a rare disease called bronchiolitis obliterans”

However Australia’s peak health and medical research body, the NHMRC falsely claims that vaping causes popcorn lung in its 2020 CEO statement on vaping and has refused to withdraw this claim, in spite of being advised of the evidence in our review in Addiction:

Reading: Minton M. Debunking the myth that vaping causes popcorn lung. Reason Foundation 2023

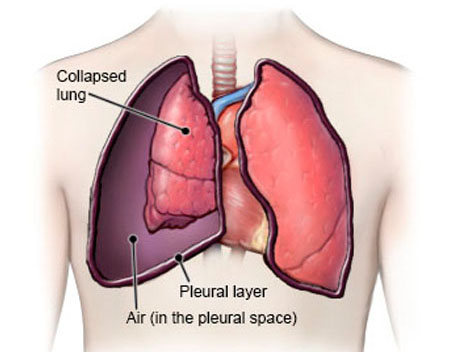

There is no evidence that vaping causes spontaneous pneumothorax.

A spontaneous pneumothorax is the sudden collapse of a lung without any apparent cause. It occurs when a congenital bleb or ‘bulla’ on the surface of the lung ruptures. Air is released from the lung into the chest cavity (pleural space) and the lung collapses.

Spontaneous pneumothorax occurs mainly in healthy young people without underlying lung disease, and can be sometimes triggered by smoking, strenuous exercise e.g., heavy lifting or severe coughing. It is most common in the 15-34-year-age group, especially in tall, thin young men. About 90% of cases in this age group are spontaneous. ‘Spontaneous’ means there is no underlying cause.

“Secondary” pneumothorax is caused by underlying lung disease. The most common cause is emphysema but also pneumonia, lung cancers, asthma, pulmonary fibrosis, and cystic fibrosis. Secondary pneumothorax is less common and occurs mainly in older people (55+).

Pneumothorax is common. For example, in England it occurs in 24 men and 10 women out of every 100,000 people each year. In fact, I personally was admitted to hospital with a spontaneous pneumothorax at the age of 20, and neither smoked or vaped.

In Australia, with 1.6 million adult vapers, most being under 40, there would be over 200 cases of spontaneous pneumothorax each year in young people who vape. This is based on 17 cases per 100,000 people per year, of which 90% are spontaneous.

The occurrence of vaping and this condition is an association. There is absolutely no reason to suggest that vaping causes spontaneous pneumothorax.

There is currently no definitive evidence that vaping increases the risk of cardiovascular harm. Long-term epidemiological studies are needed to provide more conclusive answers.

However, the potential harm is likely to be small in most cases and significantly less than that caused by cigarette smoking. The risk is greatest in heavy or long-term vapers and those with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions.

In contrast, the evidence is clear that switching from smoking to vaping substantially reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease

The evidence

1 Cross-sectional studies

Cross-sectional studies provide a snapshot of a population at a single point in time. While they can identify associations between vaping and health outcomes, they cannot determine whether vaping caused those outcomes.

Some cross-sectional studies have reported an association between vaping and a higher risk of cardiovascular issues compared to non-vapers. (Sharma; Alzaharani; Farfan; Vindyal) However, in many instances, participants who vaped had a history of smoking, and the increased harm may be attributed to their previous smoking habits. In some studies, cardiovascular events occurred before the onset of vaping.

Other cross-sectional studies have not identified any increased risk. One study of 450,000 subjects found that people who vaped but had never smoked had no increased risk. (Osei) Another study of 60,000 subjects found no increased incidence of heart disease in vapers compared to non-vapers. (Farsalinos)

2. Longitudinal studies

Longitudinal studies follow subjects over time. They are more robust and provide more reliable information.

A study of 24,000 subjects found that vapers who had never smoked had the same risk as non-vapers after five years follow-up. (Berlowitz) Another study found that vapers did not have an increased incidence of heart attack or stroke compared to non-vapers and non-smokers after five years. (Hirschtstick)

3. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies

An analysis of 20 studies (14 cross-sectional and 6 longitudinal) involving nearly 9 million people did not find an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease in people who exclusively vaped compared to those who had never vaped or smoked. (Chen) The authors point out that this study does not prove that vaping is risk-free to the cardiovascular system – longer studies may be needed to identify harms.

4. Dual use

Numerous studies have found that dual use (smoking and vaping) significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. (Chen; Berlowitz)

Does switching to vaping improve heart health?

The harm to the cardiovascular system from smoking far outweighs any potential risks from vaping (Peruzzi; Ding; Sharma)

Switching from smoking to vaping has been shown to reduce cardiovascular risk. Research has documented improvements in cardiovascular health in the short term (Caruso), within one month (George), and also at three and six months. (Klonizakis)

Studies have demonstrated significant improvements in blood pressure control among smokers with hypertension who switch to vaping, with benefits observed at a 12-month follow-up. (Farsalinos; Polosa) Additionally, both heart rate and blood pressure tend to decrease after switching from smoking to vaping. (OHID p956, 963)

Biological Plausibility: How might vaping cause harm?

While most of the toxic chemicals found in cigarette smoke are absent from e-cigarette vapour, some toxicants are present which could impact cardiovascular health. These include acrolein, oxidizing chemicals, volatile organic compounds (such as acrolein and benzene), and trace metals. However, these substances are present at much lower levels in vapour than in smoke. (OHID)

Studies in cells, animals and humans have found that vapour can affect cardiovascular health in several ways, the most potent being oxidising stress (harm to blood vessels from free radicals). Other mechanisms of harm include inflammation, sympathetic activation (increased pulse rate and blood pressure), platelet activation (increased stickiness in platelets leading to blood clots), harm to blood fats and endothelial dysfunction (damage to the lining of the arteries).

The risk to to human health from these findings is possible but uncertain. (Benowitz) Importantly, these effects are less pronounced compared to those caused by smoking. (Middlekauff; Ikonomidis)

What about the effect of nicotine?

Nicotine has well-documented effects on the cardiovascular system and could pose a risk for people with existing cardiovascular conditions. (Benowitz) However, these risks are much lower than those associated with smoking.

Nicotine increases heart rate and blood pressure, makes the heart work harder, and constricts blood vessels. It can also trigger arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat), cause insulin resistance (leading to elevated blood glucose levels) and may result in lipid (blood fat) abnormalities. Additionally, nicotine might damage the lining of the arteries. (Benowitz)

However, in the short term, nicotine use appears to pose minimal risk. A review of 42 clinical trials using nicotine products for up to 12 weeks found no significant increase in cardiovascular events. (Kim)

Furthermore, long-term users of Swedish snus (a product that delivers high doses of nicotine) do not have higher rates of heart attack or stroke compared to non-users. (Hansson)

Conclusions

1️⃣ There is strong evidence that smokers who switch to exclusive vaping substantially reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease.

2️⃣ There is no good evidence that exclusive vaping increases cardiovascular disease, although longer studies are needed to confirm this. Nevertheless, it is best not to vape if you are not a smoker or former smoker.

3️⃣ Dual use (smoking and vaping) significantly increases cardiovascular risk.

Many studies have found that adolescents, young adults and adults with depression are more likely to try vaping. (Lechner; Saeed; Gorfinkel; Javed). However, despite claims by some anti-vaping advocates, there is no evidence that vaping causes depression.

In fact, nicotine relieves depression and many people vape nicotine to make themselves feel better (known as “self-medication”). Nicotine acts in the “reward centre” of the brain to release the hormone dopamine, which creates pleasure. It also releases other chemicals in the brain, relieving anxiety and improving mood.

Adolescents often report vaping for stress relief. In the 2021 Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, the most commonly reported reason for vaping was to relax and relieve tension. A report by the NSW Office of the Advocate for Children and Young People in 2023 found that many young people use vaping as a coping mechanism “to manage their distress”. Vaping helped them deal with stress from home and school.

Higher levels of depression are associated with a faster escalation of e-cigarette use.

The beneficial effects of nicotine also partly explain why smoking rates are much higher in people with anxiety disorders and depression. However, smoking is deadly and smoking does far more harm overall than good.

One downside is that vapers who become dependent on nicotine can develop withdrawal symptoms when they cease vaping. These symptoms can include anxiety, loss of concentration, low mood and insomnia. In most cases these symptoms resolve over a couple of weeks. They are short-term and can be unpleasant, but are not harmful or serious.

It is best not to vape or smoke in pregnancy, however vaping is certain to be safer than smoking for the mother and foetus and is an effective quitting aid in pregnancy.

Safety in pregnancy

Unlike smoking, studies of vaping in pregnancy (here, here, here and here) have found little or no effect on birthweight, nor any increase in the risk of adverse birth outcomes.

A large randomised trial of 1,140 pregnant smokers by Hajek found that the safety of vaping was similar to nicotine patches and women who vaped were less likely to have babies with low birthweight (<2,500g). A recent re-analysis of this trial by Pesola found that pregnant women prefer vaping to NRT and “high quality evidence” that vaping “does not appear to be associated with any adverse outcomes“. The study also found

- Vapers have pregnancy outcomes similar to non-smokers

- Vapers had less cough and phlegm than NRT users

- The safety of vaping did not differ from using NRT

Women who smoke who switch to vaping in pregnancy should aim to stop smoking completely for the best results.

Nicotine replacement products such as patches, gums and lozenges are approved for use in pregnancy in Australia. Human studies here and here have not shown any clear harms from their use, such as stillbirth, premature birth, low birthweight, admissions to neonatal intensive care, caesarean section, congenital abnormalities or neonatal death.

Very high and chronic use of nicotine has been linked to harmful effects on the foetus in animal studies. However, there is no evidence that these findings apply to humans. Nicotine may not be completely safe for the pregnant mother and foetus, but it is always safer than smoking.

Quitting smoking

Although it is not risk-free, vaping has a role as a substitute for pregnant women who are unable to quit smoking with other methods. It should not be used by women who do not smoke.

A randomised controlled trial of 1,140 pregnant smokers found that vaping was twice as effective for quitting as nicotine patches (6.8% vs 3.6%). A cohort study of 1,329 pregnant women found that women who vaped were more than twice as likely as other those using NRT to report abstinence late in pregnancy (50.8% vs 19.4%). Vaping may also help to prevent relapse to smoking after birth.

Breastfeeding

Women who vape are more likely to breastfeed than women who smoke and also continue breastfeeding longer.

UK recommendations

The use of vaping in pregnancy is endorsed by an important expert group in the UK, the Smoking in Pregnancy Challenge Group, a partnership between the Royal College of Midwives, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health.

The Challenge Group provides the following advice to midwives:

“Very little research exists regarding the safety of using e-cigarettes (vaping) during pregnancy, however evidence from adult smokers in general suggests that they are likely to be significantly less harmful to a pregnant woman and her baby than continuing to smoke.”

Advice from the Challenge Group

The UK Royal College of Midwives 2019 Position Statement on quitting in pregnancy states:

“E-cigarettes contain some toxins, but at far lower levels than found in tobacco smoke. If a pregnant woman who has been smoking chooses to use an e-cigarette (vaping) and it helps her to quit smoking and stay smokefree, she should be supported to do so.”

The UK National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training says, “if a person who is pregnant chooses to use a vape, and if that helps them to quit smoking and stay smokefree, they should be supported to do so.”

Reading

1. Use of electronic cigarettes before, during and after pregnancy. A guide for maternity and other healthcare professionals. Smoking in Pregnancy Challenge Group 2020

2. Position Statement. Support to Quit Smoking in Pregnancy. The Royal College of Midwives. 2019

Vaping is significantly less addictive than smoking. Smokers who switch to vaping find it easier to quit vaping (than smoking) when they are ready to try. [Shiffman 2020; Foulds 2015; Fagerstrom 2018; Hughes 2019; Liu 2018; Shiffman 2024)

Almost all former smokers who vape were already dependent on nicotine from past smoking but have transferred their nicotine dependence to a much safer product.

A comprehensive report commissioned by the UK Government in 2022 concluded that:

“the risk and severity of [nicotine dependence from vaping] is lower than for cigarette smoking”

“More addictive than heroin?”

It is wrong to say “nicotine is more addictive than heroin”. The dependence-forming characteristics of nicotine depend on how it is delivered i.e., how fast it reaches the brain and whether there are other chemicals that increase its effect.

- Smoking is particularly addictive because it delivers high levels of nicotine very rapidly to the brain. A review of 30 studies of nicotine delivery from vapes found that they deliver nicotine as quickly as smoking but to lower levels, and are therefore likely to be less addictive. (Cao 2024) However, some vaping devices can deliver nicotine as fast as smoking. (Nardone 2019)

- Smoke also contains other chemicals that make nicotine more addictive eg monoamine oxidase inhibitors. These chemicals are not present in vapour.

That is why dependence on nicotine patches is very uncommon. Less than 2% of patch users continue long-term.

A word on the definition of ‘addiction’

The urge to vape is not strictly characterised as “addiction”. According to Addiction Ontology, the definition of addiction is a compulsion to engage in a behaviour known to cause serious net harm.

Nicotine has only minor health effects and the urge to vape is best described as dependence. Dependence means having the urge to use a drug to avoid physical symptoms of withdrawal when it is ceased.

Many people do not regard dependence on nicotine from vaping as a problem as it provides many beneficial and enjoyable effects.

Switching from smoking to vaping is simply changing the source of nicotine from a deadly delivery system (a cigarette) to a far less harmful, potentially lifesaving alternative.

With vaping, there is no burning and therefore no tar, carbon monoxide and other harmful constituents that are inhaled from tobacco smoke. Vaper is a far safer and less addictive source of nicotine.

Some former smokers continue vaping long-term to avoid relapse to smoking. However for many, vaping is a temporary transition stage and many go on to quit vaping as well as smoking.

Wrong. Even frequent vaping is far safer than smoking and each puff is far less harmful.

Smokers and vapers puff to get the right level of nicotine their brain needs. A cigarette has to be consumed in one sitting, usually in 10-12 puffs, to deliver the nicotine hit. Vapers often ‘graze’, i.e., regularly take a few puffs on their vape as needed to maintain their nicotine levels through the day.

Vapers generally get less nicotine than smokers and it is usually delivered more slowly. More importantly, the nicotine is not accompanied by the thousands of toxic chemicals in smoke from burning tobacco.

You should use your vape as often as you need to get sufficient nicotine to prevent cravings and avoid relapse to smoking.

“Exposure” by children to nicotine vapes is often reported in the media, but poisoning and serious harm are rare. Accidental ingestion of nicotine is usually followed by intense vomiting and most cases resolve without treatment.

Accidental poisoning from nicotine e-liquid is especially rare when compared to poisoning from other chemicals and medicines. However, if a child swallows nicotine e-liquid, medical advice should be sought immediately.

Poisons Information Centres document ‘exposures’ to nicotine e-liquid which are often incorrectly reported by the media as ‘poisoning’. However, the Australian government says “Poisoning occurs when someone is sufficiently exposed to a substance that can cause illness, injury or death”.

‘Exposures’ are simply phone calls about actual or potential exposure or a request for information. Calls could include an enquiry from a worried parent that a child had touched a vape or put a vape in the mouth.

In 2022, the NSW Poisons Information Centre (PIC) received 213 calls about ‘exposure’ to nicotine e-liquid by children under the age of four. No serious outcomes were reported in the media. In comparison there were 927 calls about hand sanitiser, 834 calls about dishwasher detergent and 788 calls about toiler cleaner in this age group.

The Victorian Poisons Information Centre reported low rates of exposure to liquid nicotine in 2018 and 2019. The number of cases referred for treatment was 14 in 2018 and 15 in 2019. The claim by the Health Minister (19 June 2020) that nicotine poisoning had doubled during this time period is incorrect.

There has been one death in Australia from accidental nicotine liquid poisoning. In May 2018, an 18-month old child died after drinking from an open (non-childproof) bottle of imported concentrated nicotine (100mg/mL) when the mother was mixing the nicotine with locally purchased flavours. This tragic case underlines the importance of allowing the sale of low-concentrations of nicotine liquid, so it is available in child-proof containers with warning labels.

Three other accidental child deaths have been reported globally since 2013: one each in Israel, Korea and the US.

Accidental nicotine poisoning is rare in other western countries such as the United States, United Kingdom and Canada. Most cases are mild and self-limiting.

According to a review by Public Health England, the risks of ingestion of e-liquids appear comparable to similar potentially poisonous household substances.

Any poisoning risk should be considered in the context of 21,000 annual deaths from smoking in Australia. Many of these could be prevented by the wider use of vaping nicotine.

Exposure to poisons is widespread in society and is associated with many products from which society benefits, such as bleach and laundry detergents. These are managed by common-sense, warning labels and child resistant containers – not by bans.

Rechargeable lithium ion batteries in vapes can malfunction (“thermal runaway”) resulting in thermal and chemical burns and traumatic injuries. These incidents get a lot of media attention, but fortunately are very rare and most can be prevented.

Malfunctions of this type do not occur in the popular beginner models, ie sealed pod devices and pen-style models in which the battery is built-in and not removable. These devices are regulated and have an integrated circuit (chipset) to maintain electrical safety and protect the device from overheating. It cuts out the power if there is a malfunction or if the fire button is pressed for too long.

Nearly all ‘exploding e-cigarette’ stories you hear about on the news aren’t from regulated, properly handled vaping products. They are mostly from loose spare batteries being carried around in a pocket or purse where they come into contact with metal objects like keys or coins and discharge accidentally.

‘Mechanical mods’ used by some experienced users they do not have built-in electrical protection and must be used with great care. Sometimes incidents also occur with devices which have been tampered with.

Lithium ion battery malfunctions also occur in other electrical devices such as mobile phones, laptops and electric cars.

Injuries from vapes are rare and are far less common than injuries from tobacco cigarettes. Cigarettes remain the biggest cause of fatal house fires. According to the London Fire Brigade “Switching from smoking tobacco to vaping can greatly reduce the risk of dying in a fire”.

Most incidents could be prevented by user education eg

- Plastic storage cases to avoid contact of loose batteries with keys or coins. Never carry a loose battery in your pocket or handbag

Plastic case for a 18650 battery

- Only use reputable battery brands from trusted suppliers

- Never buy recycled batteries, re-wrapped or reclaimed batteries

- Avoid “mechanical mods” which lack safety features

- Always use the supplied USB cable as the amp rating of the cable matches the specifications of your device. Connect the other end to a good quality low amp (0.5-1 amp) USB wall adapter. Check the manual for advice

- It is safe to plug the USB cable into a computer, TV or game console as they provide a low, steady electrical output

- Phone and tablet chargers are generally not suitable for charging vapes as almost all are rated ≥2 amps output and deliver too much current

- Use a dedicated battery charger for loose batteries

- Do not keep your device on charge for longer than necessary and never leave it unattended when charging. Charge the device on a nonflammable surface in case of overheating

- Replace or re-wrap batteries if the cover is damaged

- Dispose of used batteries in a recycling bin, not in the household rubbish

Reading

11 Battery Safety Tips to Keep You Protected, Vaping 360 July 2023

Quitting Smoking

Vaping nicotine is a more effective quitting aid than nicotine replacement therapy (patches, gums, lozenges) and is at least as effective as varenicline (Champix). Vaping has helped millions of smokers quit who were unable to quit with other methods.

Studies show that vaping is effective in the controlled setting of randomised controlled trials, in natural real-world studies and with or without support.

RANDOMISED CONTROLLED TRIALS

The best scientific evidence that a treatment works is from randomised controlled trials (RCTs), in which subjects are randomly allocated the treatment (in this case vaping) or something else in a carefully controlled setting and the outcomes compared. The gold standard is Cochrane reviews which pool and analyse results (‘meta-analyse’) from the best RCTs to give even more reliable results.

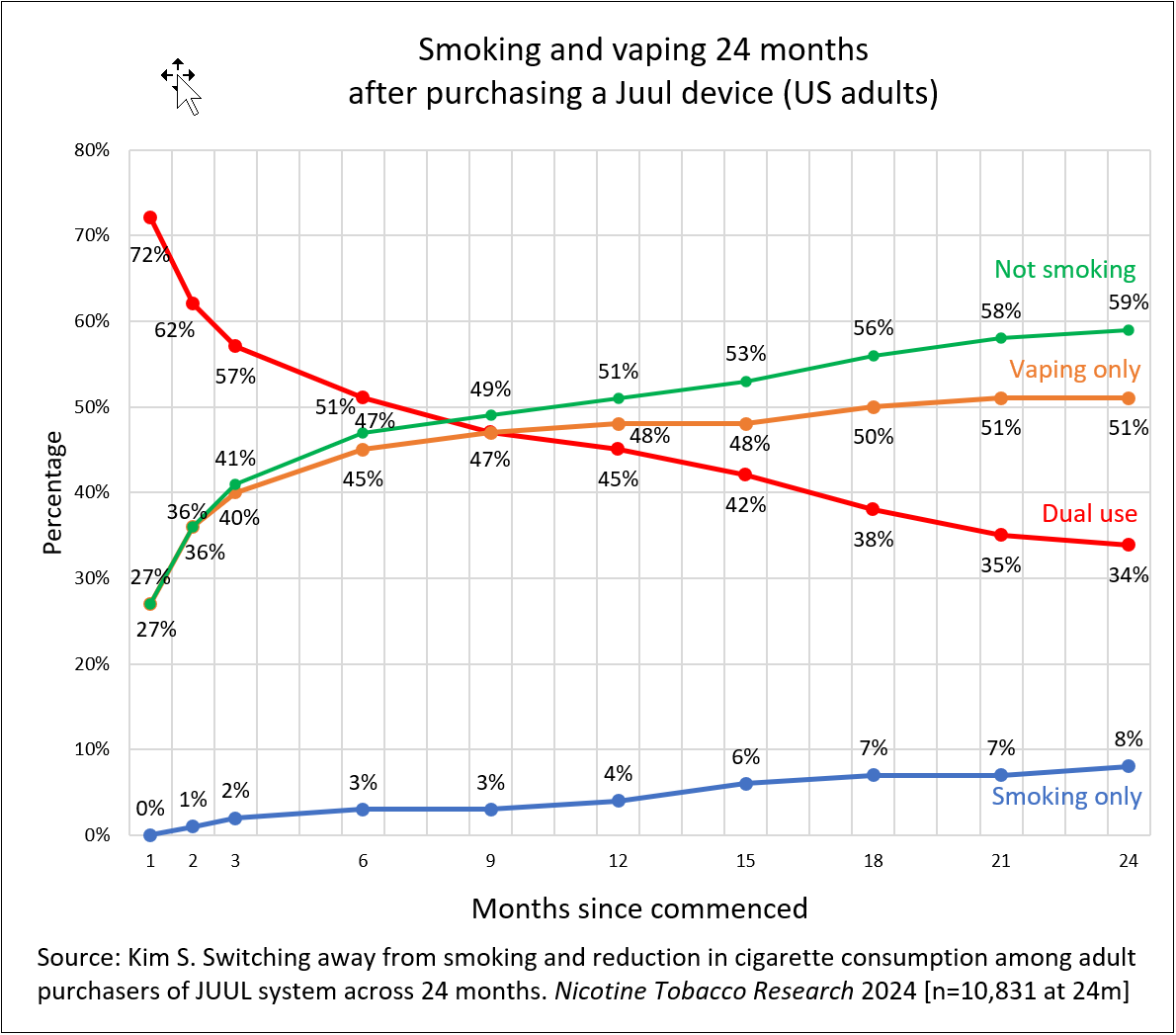

RCTs underestimate the effectiveness of vaping. RCTs are limited to short time frames, typically 6 months. Real-world studies show that many smokers quit early but others switch successfully over time, some taking 2 years or more to adjust to vaping (eg Kim 2024). These quitters are not captured in RCT results. Also in RCTs, smokers cannot chose their preferred product and must use the device and flavour supplied.

1. Nicotine replacement therapies (patch, gum etc)

A Cochrane review in 2024 compared the effectiveness of vaping with NRT as a quitting aid with professional support and found “high certainty” evidence that vaping was 59% more effective than NRT.

Other meta-analyses of the best quality RCTs concluded that vaping was 53-77% more effective than nicotine replacement as a quitting aid. (eg Levett 2023; Grabovac 2021; RACGP 2021)

2. Varenicline (Champix)

Varenicline is the most effective conventional quitting aid but is used infrequently. One RCT compared varenicline directly with vaping and found that quit rates were equally effective after 6 months. (Tuisku 2024)

A 2023 Cochrane review found high-quality evidence that nicotine vapes and varenicline (Champix) are the two most effective single treatments for quitting smoking available in Australia. The study analysed 319 randomised controlled trials of all medications used to help smokers quit and found that for every 100 people who use vapes to quit, 10-19 are likely to succeed after 6 months or more. More here.

A review by the UK National Institute for Health Research analysed 363 RCTs of smoking treatments and concluded that vaping was the most effective single therapy, followed by varenicline and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).

TRIANGULATION WITH OTHER RESEARCH

Combining different types of research with different strengths and weaknesses (triangulation) provides a more accurate picture than just RCTs alone. These studies all point to the same conclusion, strengthening the evidence that vaping is an effective quitting aid. They also show that vaping works in the real-world setting, not just in a controlled trial (RCT) setting.

1. Observational studies

Observational studies examine whether vaping works by observing its impact in a cohort of smokers in real-world settings. The findings are less reliable than RCTs but still give valuable information. The better quality observational studies show that vaping increases quitting (eg Goldenson 2021; Adriaens 2021; Kotz 2022).

2. Population studies

Multiple large population studies have found that smokers who vape to quit have significantly higher quit rates and quit success than smokers who do not vape, for example in the United States and in the United Kingdom. A study in Australia, Canada, England, United States found that smokers who initiated daily vaping were more likely to make a quit attempts and were three times more likely to have quit 12-24 months later. Non-daily vaping was not effective in increasing quit rates. Daily vapers are 3–8 times more likely to quit than smokers who do not vape.

An Australian population study by Chambers found that smokers who attempted to quit with vaping were twice as likely to have quit smoking for more than a month, 12 months later than those who did not try vaping (excluding those who vaped only once or twice). Higher quit rates are expected in a more supportive regulatory environment.

3. Declines in national smoking rates

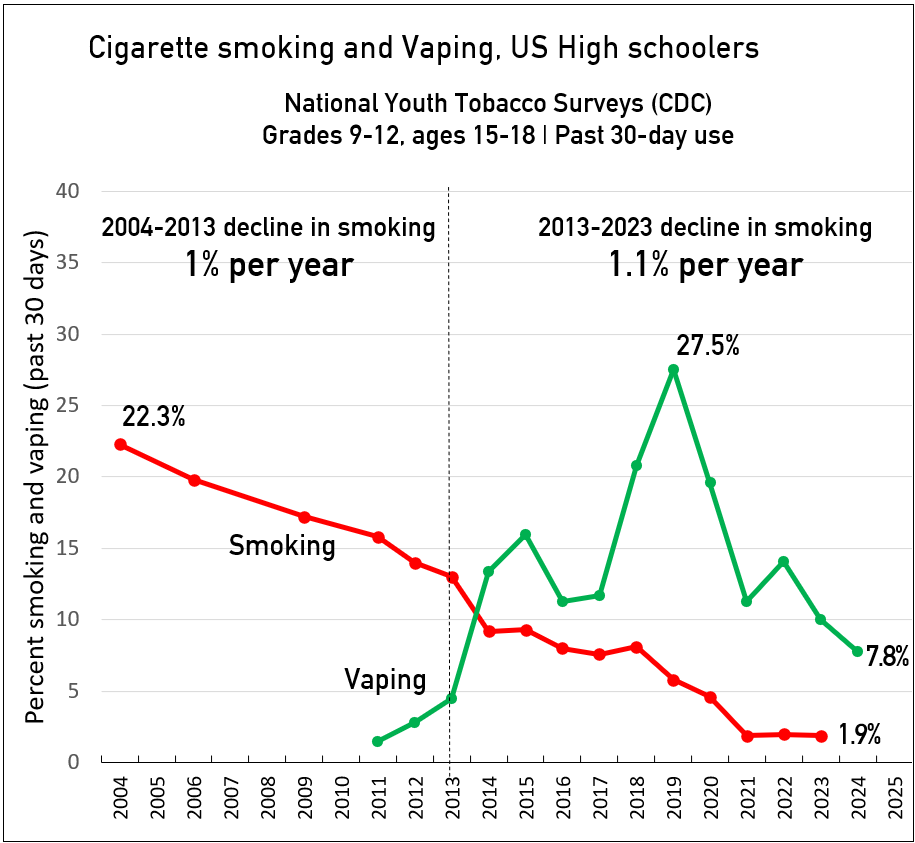

Many western countries which provide legal access to vaping have experienced rapid declines in national smoking rates (see below). Vaping is not the only factor at play but is likely to be a major contributor.

4. England Stop-Smoking-Services

Analysis of quit attempts by the Stop Smoking Service in England shows that smokers have greater success in quitting by vaping with professional support compared to any other quitting method (64.9% vs 58.6%). (OHID 2022)

5. Accidental quitters

Vaping is unique as a quitting aid in that many smokers with no intention to quit, who try vaping, go on to quit without any support. Accidental quitters are surprisingly common and are not captured in RCTs. Studies include Kasza 2021; Foulds 2022; Carpenter 2023.

6. Anecdotes

Anecdotes are the weakest type of scientific evidence. However in 2021, there were an estimated 82 million vapers globally and many more had quit smoking and vaping completely. At these levels, anecdotes can’t be ignored.

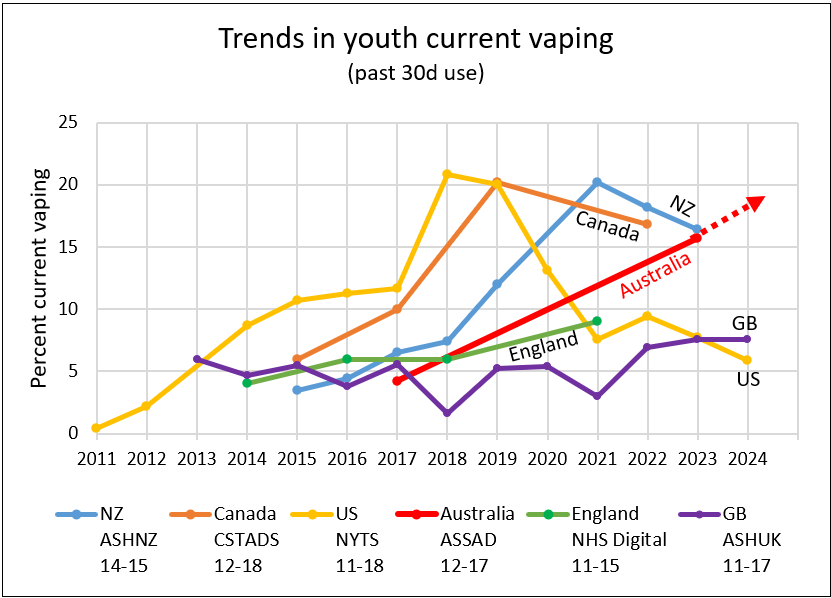

Smoking rates are falling faster in countries which adopt vaping and other reduced risk nicotine products (such as snus and heated tobacco products) compared to countries that do not.

Vapes have the potential for a substantial positive public health impact (a function of reach × efficacy), given that vapes are both more effective and have a greater reach than other approved cessation methods. Vapes are the most popular quitting aid used in Australia and in most other Western countries.

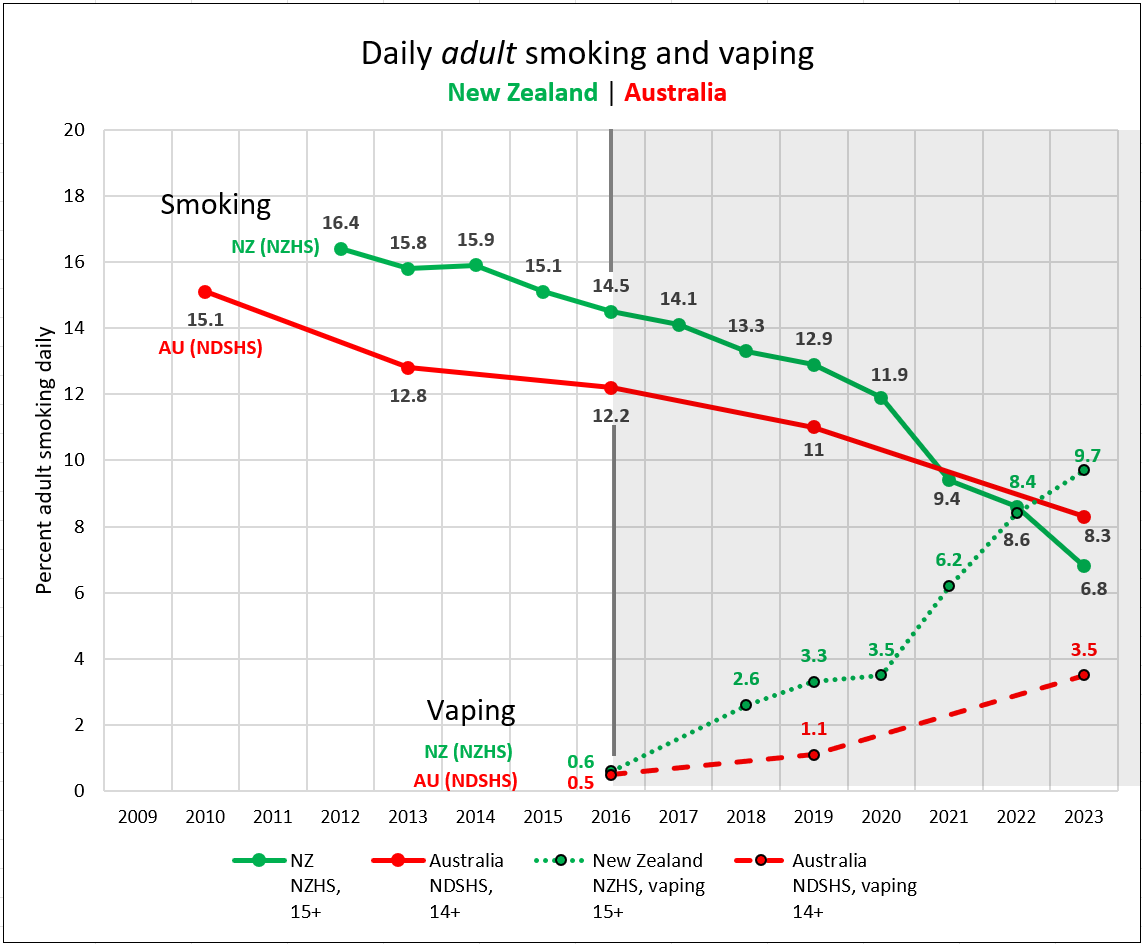

In New Zealand from 2016-2023 daily smoking declined by 53.1% from 14.5% in 2016 to 6.8% in 2023 as vaping rates increased. In Australia, during the same period, daily smoking declined 32% from 12.2% in 2016 to 8.3% in 2023. Some of this decline is likely to be due to the uptake of illicit NVPs.

Decline in smoking in New Zealand accelerated as vaping increased

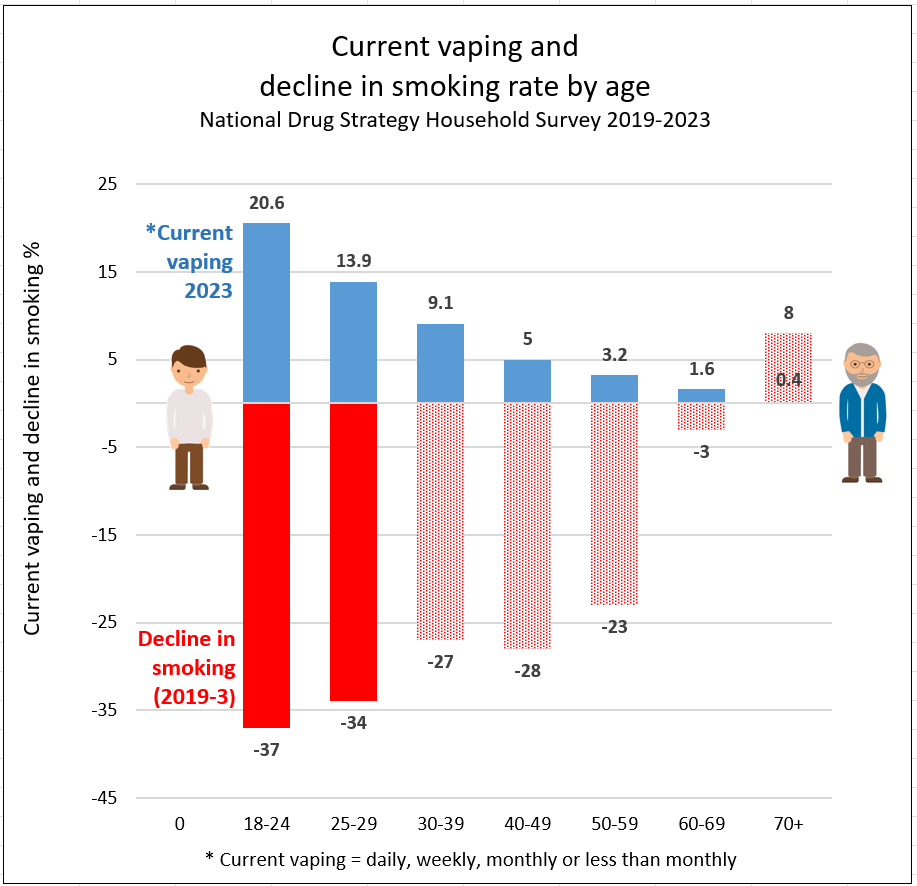

Smoking declined most in the age groups with the highest vaping rates, suggesting that vaping is a significant contributing factor (NDSHS 2023). Vapes help smokers quit and divert would-be smokers away from the deadly habit.

Decline is smoking 2019-2023 is fastest in the age groups with the highest vaping rates

Studies show that vapes function as economic substitutes for cigarettes. For instance, higher cigarette prices are associated with lower cigarette purchases but higher vaping purchases. Likewise, there is some evidence that higher e-cigarette prices are associated with higher cigarette purchases.

There is evidence that restrictions imposed on vape sales has the harmful unintended effect of driving tobacco users back to cigarettes, which are far more harmful to health.

Vaping nicotine is the most popular quitting aid in Australia and in many countries where it is readily available.

In 2023, 32% of Australian smokers used vaping to help them quit (19.6%) or reduce (12.2%) smoking. The next most popular quitting aid was nicotine replacement therapy (17%).

Vaping devices are also the most popular quitting aid in England, the United States and the European Union. Vaping devices were used in 43% of quit attempts In England in 2024 and in 27% of quit attempts in France.

Because of its combined popularity and effectiveness, the public health impact of vaping is even greater. Vapes even have a wider reach as they can assist those who are not planning to quit (accidental quitters), unlike conventional medicines.

Only short-term use is recommended but long-term vaping is safer than relapsing to smoking.

It is recommended that smokers should try to stop vaping once they have successfully quit smoking. However, for many former smokers, relapse to smoking is a constant risk. Research suggests that vaping may assist in preventing relapse. Vaping can act as a substitute for smoking behaviour to help cope with urges to smoke.

Smokers vary in the length of time they continue to vape after switching from smoking. The number vaping gradually declines over time, although some vapers need to vape long-term to prevent relapse to smoking.

How long do people vape?

About 70-80% of smokers who quit with vaping are still vaping 6-12 months later:

- An analysis of 19 randomised controlled trials: 70% of those who had successfully quit were still vaping at 6 months or longer (Butler 2022)

- A US cohort study of 2,535 smokers: 72% were still vaping 12 months later (Chen 2020)

- An RCT of 886 patients in England: 80% were still vaping at 12 months (Hajek 2019)

- In a cohort study of smokers who purchased a Juul device, 87% of quitters were still vaping at 24 months (Kim 2024)

In Great Britain, 55% of current vapers had been vaping for over 3 years, according to the annual ASH UK report in 2023. ASH UK also reported in 2024 that, among all ex-smokers who have ever vaped (including current and ex-vapers) the median length of time spent vaping was two years.

Of course, many former smokers who quit with vaping are now neither smoking or vaping.

Remember, “abstinence from nicotine is not necessarily a priority, the most urgent priority is to switch away from smoking tobacco”. (UK NCSCT)

There is no evidence that vaping causes former smokers to relapse, as claimed by some researchers (Baenziger).

Some studies have found that former smokers who later take up vaping are more likely to relapse than those who do not take up vaping. However, this association is not causal (caused by) vaping. There are two likely explanations for this finding:

- Former smokers who are tempted to relapse are more likely to try vaping to prevent going back to smoking. (Dai; McMillan) However, these smokers are already at risk of relapse. The relapse is not caused by vaping.

- Smokers who vape are more nicotine dependent than smokers who do not vape and are therefore more likely to relapse anyway, not because they vaped. (McNeill; Farsalinos)

Other research suggests that vaping is likely to reduce the risk of relapse. “Ex-smokers experience vaping as a pleasurable and enjoyable direct substitution for smoking” and this may be protective against a smoking lapse. (Notley 2018, Notley 2019)

You should only try to quit vaping when you are confident that you will not relapse to smoking as the small health risk from continuing to vape is minor compared to the harm from relapsing to smoking.

Quitting vaping is generally much easier than quitting smoking as vaping is less addictive. Some people can stop vaping abruptly, using techniques to manage urges, such as distraction and a commitment to the ‘not-a-puff’ rule.

1. Reducing nicotine and vaping frequency

You can gradually reduce the nicotine content of your vape and try to use it less frequently. Reducing nicotine levels may require an “open” vape system so you can fine tune your dose reductions. You may wish to vape nicotine-free e-liquid for a while before quitting.

You can also gradually increase the time between vaping sessions and set rules for when and where you do and do not vape to gradually reduce use. Try limiting vaping to certain places, times or situations.

2. Behavioural strategies

Behavioural strategies that are used to quit smoking may help. These include

- Distraction. Distract yourself when you get a craving by doing something else. Go for a walk, do some deep breathing, do some chores

- Avoidance. Some triggers can be really hard to deal with, such as vaping while drinking or vaping with friends. It may be best to avoid those situations for 2-3 weeks until you feel stronger.

- Delay. Cravings only last 2-3 minutes on average, although they feel like a lot longer! If you can delay the thought of vaping for 10 minutes, for example, until a certain time or after completion of a task, the craving will almost invariably be gone.

- Escape. If the pressure is mounting and you think you are going to crack, just leave! Go home, go for a walk, just get out of there!

3. Lifestyle changes

Other lifestyle changes can help, such as keeping busy, doing regular exercise, relaxation strategies and drinking less alcohol.

4. Medication

Some people benefit from switching to nicotine replacement therapy, such as patches or gums, as a step to quitting. There is some evidence that a course of varenicline tablets (Champix) can also help you stop vaping. This needs to be prescribed by your doctor.

However if there is any risk of relapse to smoking you should continue vaping.

After quitting, it is a good idea to keep a vape or faster-acting NRT (eg gum or lozenge) at hand for ‘emergency’ situations when a sudden trigger causes an urge to smoke.

Further information

Supporting clients who want to stop vaping. National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training, UK. 2022

Wahhab M. Clinicians guide to supporting adolescents and young adults quit vapes. Sydney Childrens Hospital Network 2023

A Guide to Support Rangatahi (children) to Quit Vaping. NZ Asthma and Resp Foundation 2023

Youth vaping

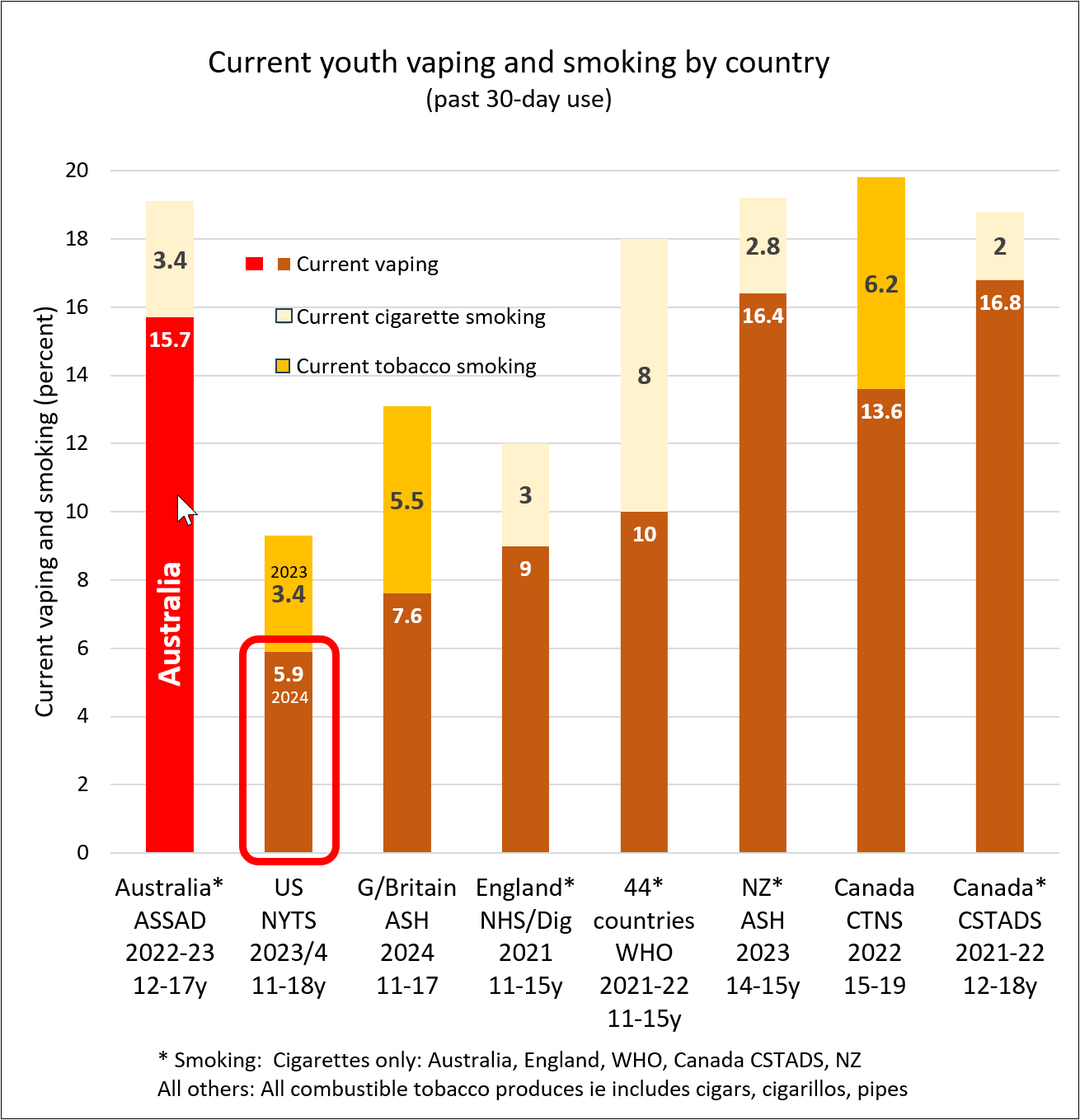

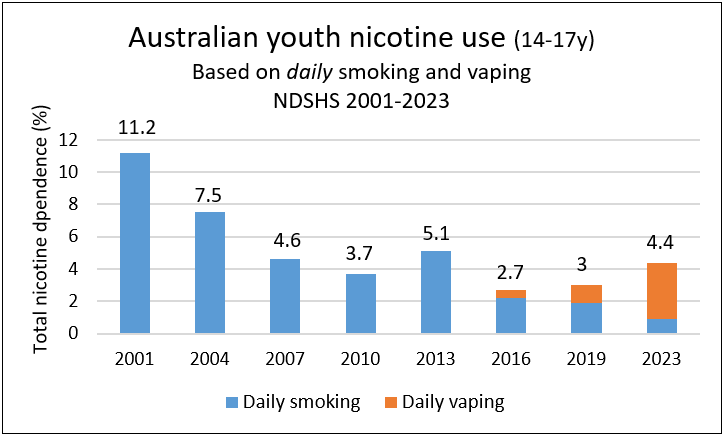

About five percent of young people in Australia who have never-smoked vape frequently. Most youth vaping is experimental and short-term. This is a far cry from the alarmist media headlines of a youth vaping ‘epidemic’.

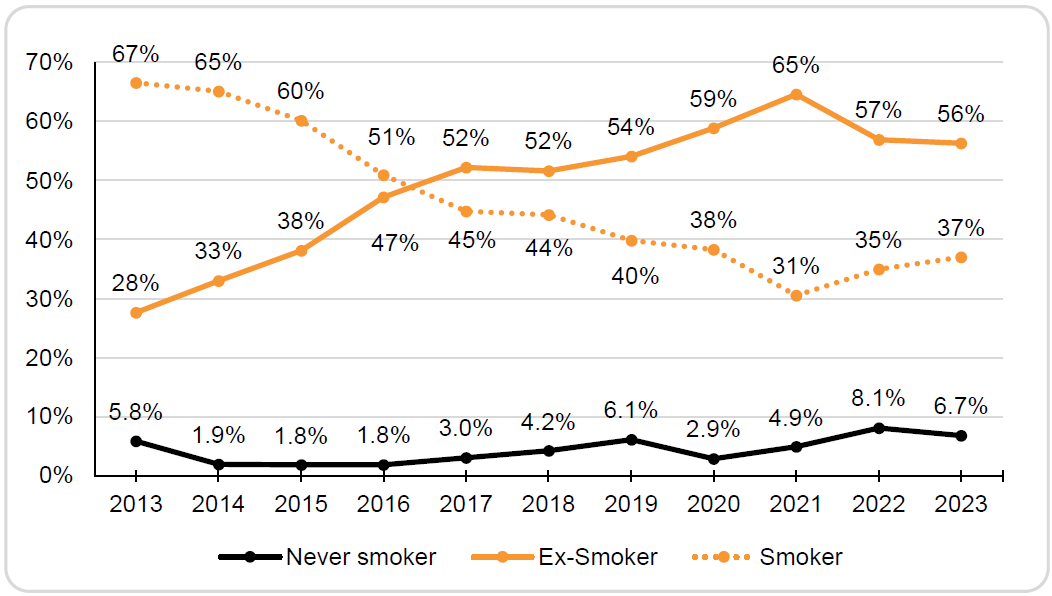

From a health point of view, the main concern is for never-smoking teens who vape frequently as this is the group at risk from new and potentially harmful inhaled chemicals. However, frequent vaping is mostly by adolescents who are or have been (or would be) smokers. Vaping for this population is likely to be beneficial.

Media reports usually refer to lifetime (ever-vaping) or past-12 month vaping. These measures exaggerate the risk as most teen vaping is experimental and short term, especially by never-smokers.

The research

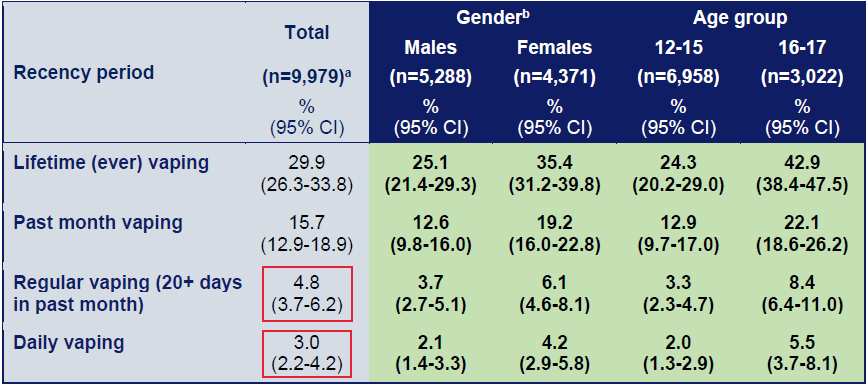

The Australian Secondary Students’ Alcohol and Drug Survey (ASSAD) in 2023 surveyed nearly 10,000 12-17-year-old secondary school students. Of these 29.9% had ever tried vaping and 15.7% vaped in the last month.

Only 4.8% vaped ≥20 days in the last month and 3% vaped daily. 31% of vapers had already tried smoking or currently smoked, so overall around 5% of never-smoker were frequent vapers.

Vaping by age and gender in secondary school students 2022-23 (ASSAD)

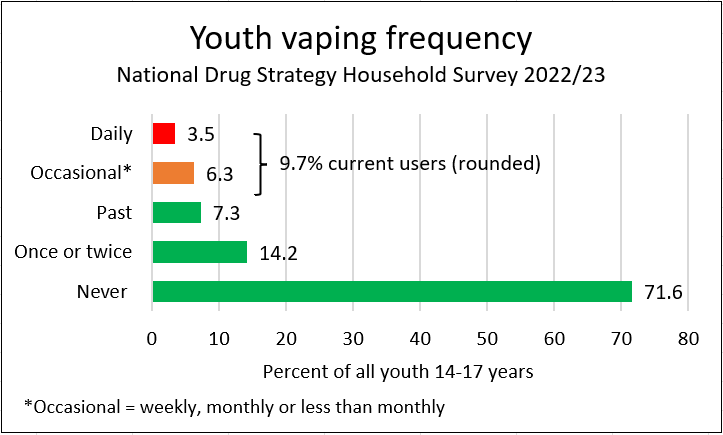

The National Drug Strategy Household Survey in 2023 surveyed 560 14-17-year-olds. Of these, 28.4% had tried vaping. However half of these (14.2%) had only vaped once or twice.

Only 3.5% vaped daily and an estimated 3% vaped 20+ days per month, but not daily (6.5% total). Some were smokers who switched to vaping (21% had smoked first). So an estimated 5% of never-smokers vaped frequently (80% of 6.5%). Some of these young vapers would have become smokers if vaping was not available.

Youth vaping frequency (NDSHS 2023)

Other countries

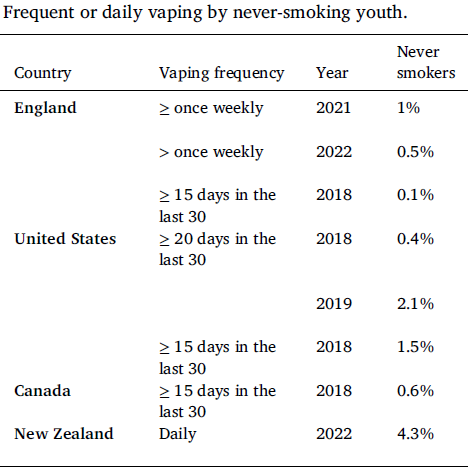

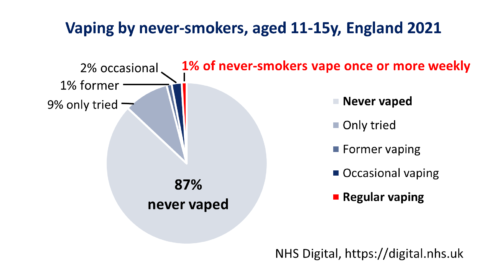

Frequent vaping by young never smokers is generally <2% in other western countries. (reference)

For example, in England in 2021, 7% of youth aged 11-15 years were currently vaping. [NHS Digital] However only 3% of never-smokers currently vape (1% at least weekly, 2% less than weekly).

Further reading

Mendelsohn CP, Hall W. What are the harms of vaping in young people who have never smoked? Int J Drug Policy 2023

Blog post. Frequent vaping by teen non-smokers is very uncommon in Australia, August 2023