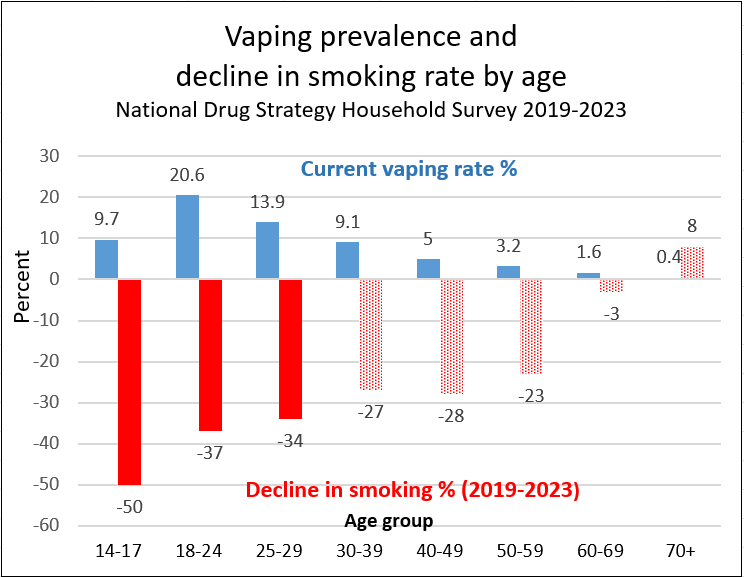

AFTER YEARS OF STAGNATION, the latest National Drug Strategy Household Survey has reported an accelerated decline in adult daily smoking, from 11% in 2019 to 8.3% in 2022/23. This 25% decline in smoking (6% per year) is twice as fast as in the previous 9 years (3% per year).

The more rapid fall in smoking reflects the rise in adult daily vaping which tripled from 1.1% in 2019 to 3.5% in 2023.

Vaping is almost certainly the main cause of this faster decline in smoking. There were no other significant changes in tobacco control in Australia during the survey period

This is a huge step forward in combatting the leading preventable cause of death and illness in Australia.

The changes mirror the remarkable decline in smoking in New Zealand as vaping rates increased. After daily vaping increased above 3.5% in New Zealand in 2020, the daily smoking rate plummeted and is now 6.8%.

Vaping was by far the most popular quitting aid reported by Australian smokers, used in 32% of attempts to quit or reduce smoking, and was twice as popular as nicotine patches and gum (17%). Vaping is also the most effective quitting aid.

The combination of vapes being both popular and effective explains why they have more impact on smoking rates than any other intervention

Vaping was most common in the 14-29 year age group. Not surprisingly, the highest smoking quit rates were also in this younger population as shown in other research. Vaping was rare in the over 60s and the smoking rate did not decline significantly in this population. More education and vaping support should also be provided to older smokers.

Youth smoking and vaping

Despite claims by the Health Minister and his advisers, the uptick in youth vaping has not led to increased smoking by youth (14-17-year-olds). In fact, daily youth smoking fell by 53% from 1.9% in 2019 to 0.9% in 2023 (10,000 daily vapers). The numbers in 2023 were so small, they could not be guaranteed as accurate.

This is at odds with the Health Minister’s repeated false claim that “Tragically, the only cohort in our community where cigarette smoking is on the rise is the youngest members of our community.”

The data provide further evidence that, rather than being a gateway to smoking for youth, vaping is more likely diverting youth away from smoking

Young non-smokers should not smoke or vape, but these figures represent a massive public health win overall. Most vaping by young never-smokers is experimental and short-term and carries relatively minor health risks.

However, for young people who vape instead of smoke, there are huge health benefits which far outweigh the small risk to the occasional recreational user.

Is prohibition working?

The adult vaping rate has risen significantly despite the de facto prohibition imposed by the Health Minister. A total of 1.5 million adults now vape.

Australians have rejected the Health Minister’s interference and attempt to control vapes as medical devices. Eighty seven percent of vapers reported not having a prescription and vaping illegally.

The outcomes for public health could be so much better if the Australian health system actually supported and encouraged smokers to switch to the far safer alternative, instead of actively trying to stop them

Reference

The NDSHS is a triennial survey of legal and illicit drug use by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The latest survey was carried out during 2022 and 2023 and involved over 21,000 Australians 14 years and older.

Expert reaction from the Australian Science Media Centre. 29 February 2024

ANTI-VAPING ACTIVISTS Becky Freeman and Simon Chapman claim that Australia does not officially ‘ban’ vaping because vapes are available on prescription. However, this semantic argument overlooks the practical realities faced by vapers every day.

The essence of a ban is to prevent access or to make access so difficult that it becomes impractical for the average person to follow the preferred legal pathways.

By this measure, Australia’s vaping regulations are a “de facto” ban, effectively curtailing legal access to vaping products and pushing consumers toward illicit channels

All prescription medicines are also “banned!”

Simon Chapman likes to say that if the prescription vaping model is a ban, then all prescribed medications must also be seen as banned.

However, this ingenuous comparison ignores the very real barriers faced by vapers that medical patients do not experience in getting prescription medicines

Most GPs are poorly informed and skeptical about vaping and many lack the knowledge or confidence to even discuss the issue with smokers. Most are not willing to write nicotine prescriptions. Many vapers report going to multiple GPs and being refused a prescription for their lifesaving ‘medicine’.

As Dr Carolyn Beaumont explains, sourcing preferred vapes from a small range of pharmacies is already a nightmare, and will only get worse after 1 March 2024, when overseas imports will be banned. Pharmacists have shown little interest in stocking vapes and know very little about them. Very few sell vapes and only a very limited range of products is available.

As a result, only 7-8% of Australia’s 1.7 million vapers have a prescription and source legal supplies from local pharmacies or overseas providers.

Under the new regulations to begin on March 1, the products available will be fewer, less appealing, more expensive, and more difficult to access. The vast majority of vapers will continue to source supplies from the black market to fulfill their needs, a clear indicator of the disconnect between legislation and the real-world behaviours of consumers.

The Australian vaping ban is similar to the Prohibition of alcohol in the US from 1920-1933, during which alcohol was also available on prescription for medicinal purposes. Prohibition was a huge failure and led to unintended consequences, such as increase organised crime and corruption, smuggling, bootlegging of dangerous and stronger alternatives, overloading of the courts and prisons, and loss of tax revenue.

Alcohol prescription during the Prohibition period in the US

A “Clayton’s” prohibition

Make no mistake. While Australia’s vaping regulations may not constitute a ban in the strictest legal sense, it has all the classic hallmarks of prohibition

- The market is controlled by criminal networks

- Criminal gangs are engaged in a turf war to control the market with widespread firebombings and killings

- Profits are laundered and used to fund other criminal activities

- Products are unregulated and less safe

- Vapes are freely sold to youth

- Law enforcement is essentially ineffective and there is widespread and easy access

The parallels with past prohibitions are striking. History has taught us that banning a popular product does not cause it to disappear. Instead, it drives it underground, criminalises users and exposes them to additional risks from unregulated products and markets.

At the heart of Australia’s vaping debate lies a paradox: a product that is both available and inaccessible, legal yet practically banned. To argue otherwise is naïve and ignores the reality that vapers face every day.

SOURCING YOUR PREFERRED VAPES through pharmacies will be a nightmare under the new rules being introduced on 1 March 2024. Dr Carolyn Beaumont is an Australian GP and vape prescriber and she explains the new rules and the challenges vapers will face.

Australian vapers have needed a prescription for nicotine e-liquid since October 2020. But at least they were able to buy their preferred products via personal importation, usually from a wide selection in New Zealand. The various consumables such as replacement pods were accessible without any script requirements.

The prescription model has so far, in my view, been a dismal failure. Very few doctors will prescribe nicotine e-liquid, with the majority of scripts being issued by a tiny minority of doctors.

But this pales into insignificance compared to the extra barriers ex-smokers will face from March 1. All overseas personal importation will be banned, including e-liquid, as well as vaping accessories such as empty refillable vapes, replacement cartridges, and coils.

Incredibly, from 1 March 2024 all e-liquids, vaping devices and vape accessories will need a doctor’s prescription and can be legally supplied only by pharmacies

As a vape prescriber, I have spent many months talking to hundreds of pharmacists nationally. Very few pharmacies are prepared to stock vaping products. These are the main issues I have identified in discussions with pharmacists:

- They don’t know what brands to stock and how to access them (with a couple of significant exceptions, most vape brands are unknown).

- They don’t see much demand in their local area

- They have limited shelf space, and are only prepared to stock a couple of brands

- They aren’t convinced of the financial benefit of investing time and money into vapes

- They are wary of committing financially to a product that may not sell within its shelf-life. They need stock that moves fast, with a demonstrated consumer demand

- They don’t know the legalities, and don’t have the wholesaler/importer contacts who can get a vaping import licence from the Office of Drug Control. Even if the pharmacist is interested in importing products, they are not allowed to be both pharmacist and wholesaler/importer of vape products.

- They aren’t convinced of the harm reduction benefits of vaping compared to smoking

- The pharmacy is co-owned, which requires more people to agree on stocking vapes

- Some pharmacy chains have already established supply from particular brands, and they aren’t open to stocking other brands

If you think that doctors and pharmacists don’t know which vape to supply, that is nothing compared to trying to get a script and supply of your favourite device’s replacement pod.

Does the government really expect doctors to know which brands to prescribe, how often a device needs replacement pods, what wicks and coils to prescribe and how to advise on correct and safe use? And do they really expect pharmacies will stock these products?

So it has fallen to a small number of online pharmacies to fill this void, just as a small number of online doctors manage the vast majority of Australian vapers who go to the trouble of getting a script.

From 1 March, I anticipate the prescription/pharmacy supply model becoming mostly an online e-commerce industry. Needless to say, the vape and cigarette black market will continue to thrive

To Australia’s pharmacists and doctors: be prepared to become pseudo vape stores. Be prepared for questions about rebuildable atomizers, sub-ohm tanks, decks, nicotine salts versus freebase, and the benefits of Kanthal versus Nichrome coils.

Or not. Hey, vapers can always return to the black market or smoking. Cigarettes never sounded so good.

Author

Dr Carolyn Beaumont, GP and prescriber of vapes for smoking cessation. www.medicalnicotine.com.au

IN THE LAND DOWN UNDER, a burgeoning illicit market for vaping products paints a stark portrait of failed prohibition. Australia’s stringent anti-vape stance has inadvertently but predictably nourished a thriving underground economy, with ramifications echoing the lessons of 20th-century drug bans.

Published in Filter magazine 14 Feb 2022. Available online here

The intricate web of negative consequences underscores the urgent need for a paradigm shift towards regulation and harm reduction. On February 12, some colleagues and I released a briefing paper to launch a campaign to raise awareness of these self-inflicted problems.

Australia is the only country in the Western world to require a nicotine prescription to vape legally. The restrictions are so harsh that they amount to de facto prohibition. This has led over 90 percent of Australia’s 1.7 million adult vapers to give up on legal pathways and purchase their vaping products from the illicit market.

This market is not a fringe phenomenon but a mainstream crisis, with an estimated 120 million disposable, unregulated vapes imported illegally from China each year. Products are brazenly sold in retail outlets and across social media platforms, without consumer protections, to both adults and minors.

The irony is stark: Measures ostensibly intended to safeguard public health are putting people at risk in a number of ways beyond the sabotage of smoking cessation.

Illegal vapes are a highly profitable commodity. A disposable vape can be purchased from China for as little as AU$3 and sold in Australia for AU$35. Given those huge margins and the impossibility of enforcing such a widespread market, the incentives to participate are strong.

By nurturing this lucrative domain for illegal enterprises, Australia has created a battleground for organized trafficking networks. Firebombing, public executions and daylight robberies signify an intensifying turf war among various factions, from groups with roots in the Middle East to outlaw motorcycle gangs. These acts of violence can involve the exploitation of young, marginalized recruits who carry out attacks, and their subsequent criminalization.

Isolated law enforcement busts are often celebrated in the media, but represent a drop in the ocean. Research has shown that illicit markets, in Australia and overseas, have rarely been significantly disrupted by enforcement or crackdowns. This has been the case with alcohol, with other drugs, with sex work and more. Further research has found that drug-law enforcement, by creating power vacuums and instability in illicit markets, can increase associated violence.

Even the head of the Australian Border Force (ABF) has warned that banning vapes at the border, a policy being implemented right now, won’t eradicate the illicit market. Already, he estimated, the ABF was only managing to detect a quarter of illicit drugs making their way into Australia. That’s likely an overestimate.

The ABF’s limited success in intercepting illegal vapes illustrates the futility of trying to impose this type of border control here. Australia has a vast coastline, and the ABF has nowhere near the resources to constantly patrol it all. The force scans just 1.4 percent of the 6.3 million containers that arrive in Australia by sea every year. The rarity of prosecutions highlights the low risk of trafficking and the failure of enforcement to make any significant dent.

The parallels with past prohibitions are striking. Heroin was banned in Australia in 1953 but is widely available. Illicit tobacco, avoiding heavy taxes, is now estimated by industry sources to comprise 23.5 percent of the total tobacco market. In 2022, a ban on tobacco in Bhutan was repealed after it led to a thriving illicit market, associated violence and corruption, and increased tobacco use.

Banning drugs doesn’t stop people from using them. Instead, it drives them underground, exposing them to additional risks from unregulated products and markets. Sellers always rise to meet the demand and find creative solutions, regardless of legal barriers. Australia’s failure to learn from historical precedents suggests a disconcerting disregard for evidence-based policy-making.

According to the Iron Law of Prohibition, banned substances not only become more potent and dangerous but also more accessible to vulnerable populations, such as youth. A tragic example of this is the outbreak of the severe and sometimes fatal lung injury misnamed as “EVALI” (E-cigarette, or Vaping, product use-Associated Lung Injury) in North America in 2019-20. It resulted from illicit THC vapes, adulterated in the unregulated supply chain with vitamin E acetate.

Easy access to unregulated sales channels for minors undermines the key rationale of Australia’s prohibitionist approach. Youth vaping rates in Australia remain similar to New Zealand and other Western countries with a more liberal approach. And making vapes difficult to access, if it were achieved, would risk perpetuating youth smoking, which is far more dangerous.

The economic implications of vaping prohibition are also substantial. A huge illicit market represents a significant loss in potential tax revenue for the government, funds that could support public health initiatives.

The disconnect between public opinion and policy is another critical aspect of the vaping debate. A recent survey found that 88 percent of Australians support regulating vapes as an adult consumer product, like tobacco and alcohol. This growing public sentiment could serve as a catalyst for policy change, urging lawmakers to reconsider the current prohibitionist stance.

The contrast between Australia’s vaping landscape and that of countries like New Zealand, where a regulated market has effectively deterred a significant illicit market, is stark. Illicit vape markets are well documented in the United States and United Kingdom, but they’re much smaller in proportion because vapes are legally available at retail outlets.

The solution to Australia’s vaping dilemma lies in following New Zealand’s vapes blueprint by embracing regulation over prohibition. The only way to significantly reduce an illicit market, as the government would presumably wish to do, is to replace it with a legal, regulated one—with products sold by licensed legal outlets, with quality control and age verification. This approach would ensure product safety, curtail violence, reduce youth access and align Australia with global best practice in harm reduction.

The narrative of vaping in Australia is a further cautionary tale about the perils of prohibition. As well as being a harsh lesson for Australian regulators, it should also serve as a warning to other countries considering their own vape policies.

References

Mendelsohn CP. Australia’s Vape Prohibition Replicates Drug-War Disasters. Filter 14Feb2024

DURING A WEEK-LONG VISIT TO AUSTRALIA, Action for Smokefree 2025 (ASH) has been engaging with Australian policymakers to develop a best-practice vaping regulatory framework.

Smoking and vaping policies were very similar in Australia and New Zealand until 2020 when the four major political parties in New Zealand accepted vaping as an important tool to accelerate the decline in smoking rates.

Since 2020, New Zealand has had a regulated vaping market that allowed a wide range of vapes to be sold as adult consumer products.

The New Zealand Health Surveys report that adult smoking rates have declined by 49% in the last 5 years from 15.1% in 2018 to 8.3% in 2023.

In contrast, smoking in Australian adults has declined marginally from 12.3% to 11.8% in the same period.

“The only policy difference between New Zealand and Australia during this period has been that we allow nicotine vaping sales to compete with cigarettes, whereas Australia has taken a prescription model that puts much safer vaping out of the reach of most people.

The outcome is that New Zealand has seen unprecedented drops in smoking as people switch whilst smoking rates in Australia stagnate” ASH Director Ben Youdan says.

“The heartbreaking reality is that the current restrictive policy in Australia is keeping people smoking, and the cost of this policy will be counted in thousands of smoking deaths that could have been prevented.”

Youdan also admits that New Zealand has not got it 100% right, and encourages Australian policymakers to learn from both New Zealand’s successes and failures.

“New Zealand was very slow to regulate vaping and similar to Australia, we saw a rapid rise in youth use in the years up until 2021, but then we finally had some legislation put in place.”

After controls on marketing, sales, nicotine limits, and access for people under 18 were implemented, the proportion of Year 10 students vaping decreased significantly for the second year running

Australia also has a large black market for vaping because of its severely restricted availability of legal vaping products. New Zealand doesn’t have a vaping black market

“What has stood out during my visit is learning that despite the approach of effectively banning vaping outside of prescription use, youth vaping rates in Australia have also risen to similar levels to New Zealand. It’s especially worrying to hear that this is almost exclusively the result of illicit products, with no ability to regulate or control how vaping is used as a public health tool”.

Australia has an opportunity to learn from New Zealand’s success in rapidly reducing smoking through harm reduction, and to avoid the mistakes we have made in being slow to protect young people

“Rather than looking at the evidence, Australia’s policy appears to be an irrational ban on much safer nicotine products that are saving lives in New Zealand, yet leaving cigarettes for sale everywhere. It simply prolongs the life of the tobacco industry and leaves nicotine users with only the most dangerous choice. Cigarette companies should be thanking the Australian health minister for protecting their patch. The outcomes of this are genuinely tragic.” Mr Youdan says.

“ASH strongly recommends Australian policymakers visit New Zealand as part of a diligent policy process and see for themselves how better alternatives to the prescription model prevent avoidable smoking related deaths & disease.”

What is ASH NZ?

ASH – Action for Smokefree 2025 is an incorporated society that has been campaigning since 1983 to achieve the vision to eliminate the death and harm caused by tobacco. It is a leading independent campaign voice for high quality tobacco control measures and undertakes research including the ASH Year 10 Survey – the largest survey of its type in New Zealand.

ASH is independently funded by our members, donations, and grant funding. ASH does not take funds from tobacco, pharmaceutical, nicotine or vaping industries.

According to the ASH Year 10 Survey, the proportion of Year 10 students (14-15 years of age) vaping regularly has decreased significantly for the second year running in the annual ASH survey of Kiwi youth, dropping by almost 2 percent (18.2% in 2022, 16.4% in 2023).

MEDIA CONTACT:

BEN YOUDAN: +64 21 247 3027

EMERITUS CONSULTANT ALEX WODAK: 0416 143 823

AUSTRALIAN GPS HAVE A LIMITED KNOWLEDGE about vaping and nicotine prescribing, are concerned about safety and effectiveness, have a poor understanding of the vaping regulations, and are reluctant to prescribe a product that is not approved by the medicines regulator, the TGA.

These were the findings of a detailed GP survey published today in BMC Public Health. The findings were broadly consistent with the views of overseas GPs found in a systematic review of 25 studies in 2022 by the same authors.

The study found that some GPs refused point blank to prescribe at all. Others were only willing to prescribe after all other possible treatment options had been exhausted.

The underlying issues identified were

- Most GPs are poorly informed about vaping and lack the knowledge or confidence even to discuss the issue with smokers. Most want more information about safety and effectiveness, although this is now widely available.

- GPs want practical advice on how to prescribe nicotine and how to manage subsequent treatment decisions such as stepping down the nicotine dosage.

- Many GPs feel they are at risk when prescribing nicotine, a product that is not approved by the TGA like all other prescription medicines. If there was an adverse event, GPs are concerned that they could be responsible, without the protection normally associated with an approved drug.

- Misinformation about vaping is common, such as concerns about a gateway effect and the belief that vaping “is merely switching from one tobacco product to another”.

- Some GPs were resentful that they were expected to prescribe nicotine at all, asking ‘Why do we have to be the gatekeepers?’.

It is worth noting that this feedback was from the 13 GPs who agreed to participate in the study out of 246 invited. It is quite possible that this group was more interested in vaping than those who declined an interview, so the results may be even worse.

The results of this study will not surprise most Australian vapers, many of whom report being unable to get a prescription after visiting multiple GPs

Implications for Australia’s prescription-only model

The findings cast serious doubt on the future of Australia’s prescription-only model for vaping nicotine

Australia’s 1.7 million vapers are required to get regular prescriptions from GPs to access nicotine e-liquid and vape legally. However, less than 10% of users have a prescription, and most access supplies from the black market. Without prescriptions, the whole model collapses.

To be fair, GPs are subject to constant negative messaging and misinformation about vaping from health authorities, medical associations, health charities and the media.

Many GPs report not getting requests for nicotine prescriptions, so are not motivated to spend time learning about vaping. Appropriate training is quite extensive and time consuming.

So far very little quality education has been provided. GPs particularly lack training on prescribing and providing ongoing support for vaping. Further education is promised but if it is as ineffective as the training so far, it will insufficient in most cases.

The study highlights the folly of making vaping a medical treatment. Vapes are consumer products like cigarettes and should be readily available as adult consumer products from retail outlets. Smokers are not ‘sick’ and most do not need medical care to quit, especially with vaping.

GPs have very little to offer patients on vaping. The purpose of the medical model was for GPs to support the patient’s quit attempt with expert advice. However, most vapers know far more than GPs.

An additional issue is the current primary care crisis. General practice is overloaded, has become less affordable as bulk-billing rates fall and many patients are delaying care. Adding millions of unnecessary consultations each year for vaping is worse than stupid.

Mark Butler’s medical prescription model for vaping is in a death spiral. It has created a rampant black market controlled by criminal gangs. Australian smokers are not quitting and youth have easy access to illicit products. The crisis with GP prescribing may be the final nail in the coffin

Resources

Selamoglu M et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices surrounding the prescription of e‑cigarettes for smoking cessation: a mixed‑methods systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022

NEW ZEALAND’S DECLINE IN SMOKING in the past four years is extraordinary – equivalent to what took two decades to achieve. New Zealand has recently had some of the most dramatic decreases in smoking in the world, including for Māori and highly deprived groups.

NZHerald OPINION. Robert Beaglehole and Ben Youdan, 11 Jan, 2024

Available online here (paywalled)

Last month, the New Zealand Health Survey showed the daily smoking rate is now down to 6.8 per cent in adults, half the rate in 2018. The dramatic declines are accompanied by large uptakes in vaping, leading to a tsunami of 75,000 quitters in Aotearoa in the past year

Almost a quarter of a million fewer Kiwis are now smoking daily, and it puts us in a tiny club of countries that have smoking rates under 7 per cent. What we have in common with these successful countries is people switching from smoked tobacco to less harmful alternatives

To reach the smoking goal of 5 per cent or less (that is, 95 per cent or more of all adults being “smokefree”), around 100,000 smokers need to quit over the next two years. Our decline in smoking in the last four years is extraordinary – equivalent to what took two decades to achieve.

The unprecedented progress shown in the New Zealand Health Survey should have been a cause to celebrate. Still, concern at the coalition Government’s intention to repeal the 2022 Smokefree legislation overshadowed this remarkable achievement.

Many have claimed this repeal would jeopardise the Smokefree 2025 goal. However, this is simply not the case. Predictive modelling, which contributed to the scientific underpinning of the legislation, indicated that it would take until 2040 to get smoking rates down to 8 per cent without the law. The reality is that we have already exceeded this expectation. And a closer look reveals that the three headline measures in the act were unlikely to have any impact before 2025.

For a start, the highly touted “smokefree generation” has already been achieved for people under 25. Only 3 per cent of people aged 15-24 smoked daily in 2022/23, a quarter of the rate only four years ago. Besides, the age restrictions in the act wouldn’t have taken effect until 2027.

The nature of addiction is that demand does not respond rationally to reducing supply. While ever the demand for cigarettes remains high, abruptly limiting tobacco outlets on July 1, 2024 from 6000 to 600 would not significantly impact smoking rates but could penalise the almost 300,000 people still dependent on cigarettes. In addition, a sudden and dramatic 90 per cent reduction in retail outlets from around 6000 to 600 is likely to cause unnecessary chaos, especially in Auckland, with only 30 outlets allocated for about 90,000 people who smoke; each outlet would have to serve on average, approximately two customers every minute.

Finally, removing nicotine from all cigarettes (“denicotinisation”), slated for April 2025, is a de facto ban. The policy is untested at a national level and might not be the game-changer it’s claimed to be. Whether cigarettes stripped of nicotine will encourage people to stop completely, switch to vapes, or resort to criminally supplied regular cigarettes is not known. People smoke for the nicotine released in the burnt tobacco but die from the toxins in the smoke. Understandably, cigarettes without nicotine are not proving popular, and the major US supplier of denicotinised cigarettes is facing financial problems.

The Government emphasises its commitment to reducing smoking rates, particularly by promoting vaping as a safer and more affordable alternative. Vaping could save households up to $5000 per smoker annually, particularly benefiting people in lower-income brackets.

To move forward and convince opponents of repeal that it is serious about its smokefree commitment, the Government must present a robust action plan involving both legislative and non-legislative actions. The focus must be on people with high smoking rates, which include Māori, Pasifika, older people and the most disadvantaged; half of all people who smoke live in the most deprived households in our society.

Legislative options for the Government include outright repeal, revisiting the policy later, or introducing an improved Smokefree Environments Amendment Bill. Ideally, the third option would involve retaining the retail licensing system, legalising a greater variety of safer nicotine products such as snus and nicotine pouches, and gradually reducing retail outlets over time, with a focus on fair access for adults who smoke.

Regardless of the option chosen, the Government can immediately implement necessary non-legislative measures, including:

- Enforcing penalties for sales of both cigarettes and vapes to underage people.

- Including vaping as the most effective and cheapest cessation tool in all cessation programmes.

- Promoting information campaigns to encourage reduced-harm products for adults and correct misinformation and stigma about vaping while protecting children from starting vaping.

- Ensuring that all health professionals and stop-smoking services offer reduced harm products and promote successful “swap to quit” schemes based on the UK model.

- Scanning all imported containers at the border to control illicit trade and reduce tobacco crime and loss of government revenue.

With these comprehensive measures, and even in the absence of the Smokefree 2022 legislation, the coalition Government can achieve the Smokefree 2025 goal, re-enforcing New Zealand’s reputation as a world leader in tobacco control.

Robert Beaglehole, chair, and Ben Youdan, director from Action for Smokefree 2025

Further reading

New Zealand’s Smoking Rates Plummet, While Australia’s Stall, by Cliff Douglas, 16 January 2024

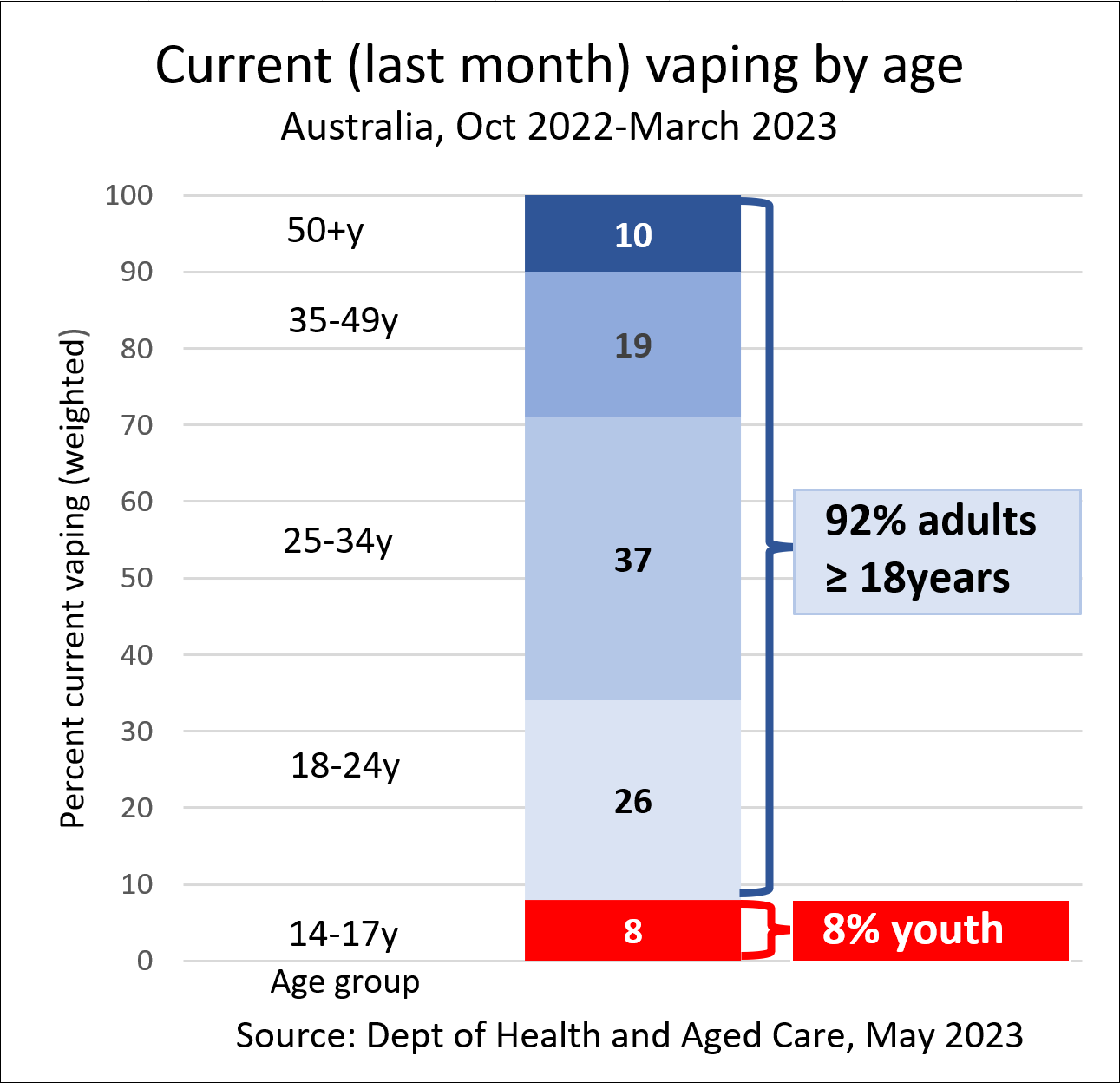

ONLY 8% OF AUSTRALIA’S VAPERS are under-18 and are at relatively minor risk of harm from vaping. However, Australia’s harsh restrictions on vaping focus on protecting youth instead of enabling the substantial benefits of vaping to the much larger number of adult smokers and vapers.

Relatively few underage vapers

The 2023 survey for the Department of Health and Aged Care found that only 8% of Australian vapers are under 18 years of age. However, government policy is disproportionately focussed on the small harms of vaping to this small minority

In doing so, policy neglects the needs of the remaining 92% of vapers who are adults aged 18 or over. It also overlooks the needs of 2.5 million adult smokers.

Harms to youth are relatively minor

Our recent Evidence Review concluded that “youth vaping carries relatively minor health risk”. This is because most young non-smokers who vape do so infrequently and transiently. Only frequent vaping over the longer-term has the potential to cause harm, and serious harmful effects to date are very rare.

Furthermore, rather than being a gateway to smoking, vaping is diverting young people who would have otherwise smoked away from smoking overall. As well, any harm from vaping is likely to be distant, after many years of sustained use.

Huge benefits for adults

On the other hand, the vast majority of adults vape to quit smoking or to prevent relapse to smoking. In young adult populations (18-34y), vaping is diverting users from taking up smoking and has accelerated the decline in smoking rates eg here and here. The health benefits of switching from smoking to vaping are substantial, immediate and lifesaving.

Policies that restrict adult access to vaping are likely to perpetuate smoking and have serious adverse public health consequences

Do the maths

The mathematics is simple. Youth vaping is a low-risk activity by <10% of Australia’s vaping population. On the other hand, over 90% of vapers are adults, most of whom would otherwise smoke, and are likely to have substantial health benefits from vaping.

Numerous modelling studies (eg here, here and here) have confirmed that the overall public health impact of vaping is positive after calculating the harms and benefits of vaping for both youth and adults.

According to the UK Royal College of Physicians, optimal public health policy should make vaping more appealing, accessible and affordable for adult smokers, while restricting access by youth. This is the opposite outcome from Australia’s regulations.

VAPING REGULATIONS ARE CONSTANTLY CHANGING in Australia and most vapers are confused. This blog provides an up-to-date summary of the current regulations at 17 January 2024 and the proposed future changes.

It is important to note that these regulations only apply to the legal market which is currently <10% of the total vape market in Australia, and is expected to reduce further.

.</FONT COLOR=”#ffffff”>

Current regulations

Prescriptions

A nicotine prescription from a doctor or nurse practitioner is required to legally possess or vape nicotine e-liquid. However, the federal Health Minister has said that vapers will not be prosecuted if they do not have a prescription. Legal action will focus on illegal imports and sales.

All doctors and nurse practitioners are now allowed to prescribe nicotine without prior approval from the TGA (under the Special Access Scheme C). The practitioner must submit a form for each individual patient to notify the TGA within 28 days. The Authorised Prescriber Scheme will continue to be available as well.

Prescriptions are not issued automatically. Under the RACGP guidelines, “It is reasonable for medical practitioners to choose not to prescribe them”. Most doctors are skeptical about vaping and are poorly informed. Further training for health care professionals has been promised, but no details are available.

The RACGP guidelines recommend that doctors limit the prescription to a maximum of 3 months’ supply. It is recommended that patients return “for regular review and monitoring”.

Premixed ‘closed’ systems are preferred to open and tank devices “so that users cannot purchase and add their own flavours”.

Accessing products

1. Nicotine e-liquid

Nicotine e-liquid is available in two forms

There are two legal pathways for purchasing nicotine e-liquids. Both require a nicotine prescription.

- From an Australian pharmacy (in-store or online)

Very few pharmacies stock nicotine vapes and a very limited range of products is available. - Personal importation

You can currently import nicotine e-liquid from overseas under the TGA Personal Importation Scheme. You can import up to 3 months’ supply at a time for personal use. Most vapers get supplies from New Zealand online vendors. You need to upload your prescription to the vendor so that it can accompany your order through Customs. The Personal Importation Scheme is set to be cancelled on 1 March 2024.

2. Disposable vapes

The importation of single-use disposable vapes is prohibited, whether they contain nicotine or not – even if you have a prescription (effective 1 Jan 2024). Importing disposables is only approved for businesses if the importer holds a licence and permit issued by the Office of Drug Control (ODC) under the PI Regulations (see here).

From1 January 2024, travellers entering Australia can only bring a maximum of 2 disposable vapes with them. (see here)

3. Refillable devices (open systems)

Currently no restrictions. Empty refillable vapes can be purchased from vape shops (most are now closed), tobacconists, online from Australian and international websites. Devices and parts can be imported from overseas.

4. Standards

Basic minimum standards apply for e-liquids under the Therapeutic Goods (Standard for Nicotine Vaping Products) Order 2021 (TGO110). Updated standards (the Therapeutic Goods (Standard for Therapeutic Vaping Goods) (TGO 110) Order 2021 (TGO 110) were released in early January 2024 here.

The standards specify a range of labelling, packaging, ingredient, nicotine concentration and record-keeping requirements for nicotine e-liquids. The standards regulate nicotine as a medicine.

.</FONT COLOR=”#ffffff”>

Proposed changes

The following changes are proposed from 1 March 2024. Some will require legislation to pass through both houses of federal parliament. Debate on this Bill is expected at the end of February 2024. Other changes can be introduced by the Health Minister or the TGA.

From 1 March 2024, all vaping products (e-liquids with and without nicotine and hardware) will be deemed ‘prohibited imports’ and all vaping liquids will only be sold in pharmacies with a valid prescription.

Accessing products

1. E-liquids

From 1 March 2024, the import of all e-liquids will be prohibited without an import licence and permit from the Office of Drug Control. The only legal source of e-liquid (nicotine and nicotine-free) will be Australian pharmacies, with a doctor’s prescription. This includes bottled refills and prefilled pods.

The Personal Importation Scheme is to be cancelled on 1 March 2024 and it will be an offence to import e-liquid from overseas for personal use. This includes bottled refills, prefilled pods and disposables.

All international couriers were notified of the import restrictions on 13 December 2023. See here.

2. Refillable devices and accessories

From 1 March 2024, it will also be an offence to import

- refillable devices (even if empty),

- parts of devices

- accessories (coils, cartridges, capsules, pods, vials, dropper bottles, drip bottles)

Businesses wishing to import approved devices and accessories will require a licence and permit issued by the Office of Drug Control (see here).

You will be able to buy a limited range of refillable devices from pharmacies only – with a prescription. General retailers and vape shops will not be able to sell these devices. It will be legal to use refillable devices and many vapers are stocking up with devices in advance.

Under the guidelines, heated tobacco products are also prohibited and require an import permit under Regulation 5A and a permit under regulation 4DA of the Prohibited Imports Regulations as tobacco products. (here)

3. Penalties

From 1 March 2024, all vaping products including reusable vaping devices (whether or not they contain nicotine) will be prohibited imports into Australia.

Section 9L of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) makes it an offence to import, as well as to export, manufacture or supply a prohibited therapeutic good. This offence carries a maximum penalty of $93,900 with harsher penalties apply to corporations importing prohibited therapeutic goods for sale.

Similarly, section 233 of the Customs Act 1901 (Cth) outlines an offence where a person:

- Smuggles any goods; or

- Imports any prohibited imports; or

- Exports any prohibited exports; or

- Unlawfully conveys or has in his or her possession any smuggled goods or prohibited imports or prohibited exports.

The maximum penalty for importing or dealing with a prohibited import under this section is a fine of up to three times the value of the goods, or up to $275,000 (whichever is greater).

Vaping products may also constitute a ‘tier 1 good’ under section 233BAA of the Act which applies to non-narcotic drugs intentionally imported contrary to the Customs Act. This offence carries a maximum penalty of 5 years imprisonment, or a fine of $275,000 or both.

Reference: here (Mondaq Lawyers)

Update. Another reference suggests the penalties for illegal importationor supply will be up to 5 years imprisonment and/or a fine of $1,252,000 (4000 penalty units x current value $313)

Reference: Mondaq Lawyers 15 Feb 2024

4. Standards

The TGA is upgrading the standards for e-liquids and devices. Some of the expected changes are:

- Flavours

Only tobacco, menthol and mint flavours will be allowed. - Nicotine concentration limits

Still undecided. The likely limit will be 20mg/mL in line with the arbitrary limit set in the UK. - Packaging

All vape products will require pharmaceutical-like packaging with nicotine content displayed. Bright colours, images and appealing names will be banned. Warning statements and an ingredient list are required. - Quality and safety

All e-liquids for pharmacy sale must be submitted to the TGA to confirm compliance with the standards, before being imported or marketed. Additional quality and safety requirements will apply. An extensive list of banned ingredients will be published. - Vaping devices

All vaping devices will become therapeutic devices requiring certification and compliance with standards

The January 2024 update of the TGO 110 standards is available here.

5. Travellers’ Exemption

From 1 March 2024, travellers entering Australia can only bring a small quantity of vapes with them. The vapes must be for use in the treatment of the traveller or someone they are caring for, who is entering Australia on the same ship or aircraft. (see here)

The maximum allowable quantity is:

- 2 vapes in total (whether disposable or reusable)

- 20 vape accessories (including cartridges, capsules or pods), and

- 200mL of vape substance in liquid form.

6. Vape shops

Many vape shops have already closed, but all are likely to close by 1 March 2024. Vape shops will not be able to sell

- E-liquids, with or without nicotine

- Vaping devices of any type, even empty; accessories

6. Proposed legislation in 2024

The Government will introduce a Bill into Parliament early in 2024, seeking to impose a domestic ban on the (see here)

- manufacture

- supply

- advertising

- commercial possession

of disposable vapes, and non-therapeutic vapes to ensure comprehensive controls across all levels of the supply chain. These changes require amendments to the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989.

References

New regulation of vapes starting January 2024, 15 December 2023

Reforms to the regulation of vapes

Vapes: information for prescribers, 15 December 2023

Importing vaping goods into Australia, Office of Drug Control 1 January 2024

Other articles

Is Vaping a Criminal Offence in New South Wales? Sydney Criminal Lawyers 27 January 2024

TERRY BARNES IS A HARDENED PULIC HEALTH CONSULTANT and a former adviser to Michael Wooldridge and Tony Abbott. After years of advocating for vaping, he realises you can’t win a debate when one side is not listening. He is reluctantly withdrawing from the fight. He explains why.

The Morrison government’s prescription model was bad enough. It treated adult vapers as addicts and treatment by doctors was optional. The New Year’s Day ban and the proposed outlawing of all vapes later this year was the last straw and Terry is “over it”. As he explains:

- There’s no point in engaging in public debate with those who refuse to listen, and who cancel, bully and denounce anyone opposing their sanctimonious puritanism

- There’s no point in arguing with my-way-or-the-highway experts who treat consenting adults – most vapers – as ignorant idiots

- There’s no point in trying to persuade federal and state ministers, who treat public health figures as oracles who can’t be questioned, and then proceed to implement public policy that not only is heavy-handed and condescending, but unenforceable

The government’s declared intention is to protect young people. Instead it will have the following effects

1. Fuelling the black market

The new regulations will drive the existing black market underground and feed the violent greed of the organised crime gangs behind it. As Rohan Pike, former head of the Australian Border Force’s tobacco strike force said this week, ‘While there is a demand for it, there will be a black market”. Pike is spot on. Where there’s big money to be made, black marketeers and gangsters will be there.

And the products supplied will be unregulated and dangerous, with a total lack of quality control “People are consuming these things and really leaving their health in the hands of organised criminals”.

2. Criminalising vapers

The ban criminalises responsible, otherwise law-abiding adults who, to reduce their health risks, choose to vape instead of smoke. This seemingly doesn’t matter to the policy puritans.

3. The crackdown will fail

If the Albanese government thinks their crackdown will crack the illicit vaping nut, they’re dreaming. Instead, they’re creating an open invitation to young thrill-seekers to pursue illicit vaping as part of their youthful rebellion. It’s crazy, but it’s official policy.

The solution is obvious but no-one is listening

The real solution to the problems around vaping, especially young people experimenting with it, is not to suppress and criminalise the practice, but to make it legal and a carefully-regulated retail product alongside the officially-approved nicotine source, ciggies

But no, the public health pooh-bahs will have none of that, so you will have none of that. They know best, you see. Ciggies are legally available but you can’t have the safer alternative without jumping through ridiculous hurdles.

After years of getting nowhere, I’m done. What’s the point in arguing with them? Is it worth the public denunciation? Is it worth the risk to one’s reputation and livelihood? Is it worth more years of banging one’s head against a brick wall? Will any of these pooh-bahs ever open their minds to positive evidence and more enlightened points of view?

No.

The die is cast, and I don’t see anything changing for years, if at all. So, I’m choosing not to stick my head above this particular parapet any longer. There are easier ways to earn a professional living.

The New Puritans have won.

This post is adapted from an article by Terry Barnes published by The Spectator Australia on 3 January 2024