The scientific evidence supports vaping to help smokers quit

Posted on August 25, 2022 By Colin

EMERITUS PROFESSOR SIMON CHAPMAN does not support nicotine vaping and outlined ten issues he calls Vaping Myths to argue his case (Medical Republic 11 August 2022).

This detailed analysis looks at the evidence behind his claims and finds that many of them are flawed and misleading and he ignores crucial evidence which contradicts his case.

1. CLAIM: E-CIGARETTES ARE 95% LESS HARMFUL THAN SMOKING

RESPONSE. Professor Chapman’s claim that the “95% safer” figure was derived from a 2014 consensus panel run by Professor David Nutt is simply not true. The estimate is derived from comprehensive literature reviews by the UK Royal College of Physicians and Public Health England.

The lead author of the PHE report, Professor Ann McNeill, told the Australian Senate Inquiry into vaping in 2021, that “Our estimate was consistent with the Nutt study but was not based on it”.

She explained further that the finding was very similar to the 2018 report of the peak US science body, the National Academies of Sciences Engineering, and Medicine, which concluded, “Laboratory tests of e-cigarette ingredients, in vitro toxicological tests, and short-term human studies suggest that e-cigarettes are likely to be far less harmful than combustible tobacco cigarettes”.

Whether vaping is 95% or 80% less harmful is not the point. There is overwhelming scientific agreement that it is far safer than smoking. It is ridiculous that Australia makes vaping, a much safer way of taking nicotine, much harder to obtain than deadly cigarettes.

2. CLAIM: WE HAVE ENOUGH EVIDENCE NOW TO CALL E-CIGARETTES VIRTUALLY 100% SAFE

RESPONSE. No credible scientist suggests vaping is virtually 100% safe. The key question is whether it is safer than smoking. Vaping is a quitting aid for adult smokers who are unable to quit with conventional interventions and who would otherwise continue to smoke. We need to remember that 21,000 Australians die every year from a smoking-related condition.

The requirement that we wait for evidence of long-term safety is a standard not used for any other medicine or treatment. In health policy, it is often necessary to act on the best evidence on hand before. While we wait for perfect evidence, up to two in three continuing smokers will die prematurely from their smoking.

The precise long-term risks of vaping are unknown, but the UK Royal College of Physicians estimates that long-term vaping is unlikely to cause more than 5% of the harm of smoking.

3. CLAIM: NICOTINE IS ALMOST HARMLESS – SMOKE IS WHAT CAUSES ALL THE HARM

RESPONSE. Professor Chapman raises concerns about the potential risks of consuming high doses of nicotine. However, smokers who switch to vaping generally maintain their nicotine levels. The low concentrations in smoke and vapour cause little harm with normal use.

According to the UK Royal College of Physicians, “Use of nicotine alone, in the doses used by smokers, represents little if any hazard to the user.” The New Zealand Ministry of Health says, “For people who smoke, nicotine itself is low harm and has little or no long-term health effects.”

Chapman refers to ‘nicotine angiogenesis’, ‘cell proliferation’ and ‘apoptosis which are associated with cancer. However, nicotine does not cause cancer in humans according to leading health authorities including the World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer, the UK Royal College of Physicians and the US Surgeon General.

There is also no evidence that nicotine impairs human adolescent brain development as Chapman suggests. Evidence for this is found only in rodent studies and the relevance of these studies to humans is speculative.

4. CLAIM: THERE’S NO REASON TO WORRY ABOUT THOUSANDS OF FLAVOURING CHEMICALS

RESPONSE. Some flavours could potentially cause harm over time and this risk needs to be monitored. However, so far, serious health effects from vaping flavours have been extremely rare.

According to a recent report for the European Commission, ‘To date, there is no specific data that specific flavourings used in the EU pose health risks for electronic cigarette users following repeated exposure.’

Flavours are an integral part of the appeal of vaping. Flavours encourage the uptake of vaping by current smokers just like flavoured nicotine gum and lozenges encourage use. Vaping flavours are associated with higher quit rates compared to non-flavoured or tobacco flavoured e-liquids and may reduce the likelihood of relapse.

5. CLAIM: PEOPLE WHO BOTH SMOKE AND VAPE USE SIGNIFICANTLY FEWER CIGARETTES PER DAY: A NO-BRAINER FOR HARM REDUCTION

RESPONSE. It is not correct to say that most people are both smoking and vaping (dual use). In the latest national surveys, dual use was 30% in the Great Britain, 27% in the United States and 54% in Australia and the number is falling each year.

In any case, dual use is less harmful than exclusive smoking because most dual users significantly reduce their smoking. Most studies show dual users have lower levels of harmful biomarkers (toxins in the body) compared to smokers and many studies show improvements in health, such as reduced blood pressure and improved asthma control.

Dual use is a normal, temporary transition phase for most smokers and millions have gone on to quit smoking and vaping completely.

6. CLAIM: MANY SMOKERS CAN’T QUIT. E-CIGARETTES ARE THEREFORE NEEDED

RESPONSE. Conventional interventions only work for a tiny minority of smokers and many are not willing to try them. A 2018 meta-analysis of RCTs of smoking medication found that only 8% of smokers had quit after 12 months. Quitting rates in the real world without support and medication are even lower.

Many Australian adult smokers are unable to quit. Between 2016 and 2019, there was no decline in the smoking rate over the age of 40 and these smokers remain at high and immediate risk of illness and death. Most smokers would like to quit but many have simply given up trying after repeated failed attempts.

Clearly additional, effective options are needed. For this reason, the RACGP has acknowledged vaping as a second-line treatment when other medications have failed.

7. CLAIM: E-CIGARETTES ARE EFFECTIVE FOR SMOKING CESSATION

RESPONSE. There is good evidence that vaping is more effective than nicotine replacement therapy and helps many smokers quit. A 2021 Cochrane Collaboration review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) found that “There is moderate-certainty evidence that electronic cigarettes with nicotine increase quit rates compared to nicotine replacement therapy (RR 1.53)”.

A recent 'network meta-analysis’ of 171 RCTs of all smoking cessation medications concluded that vaping was the most effective single therapy, followed by varenicline and NRT.

There is also abundant supportive evidence from observational studies, population studies and declines in national smoking rates. Combining these different types of studies (triangulation) adds additional confidence that vaping is an effective quitting aid.

8. CLAIM: NATIONS WITH HIGH VAPING RATES ARE SEEING FASTER DECLINES IN SMOKING

RESPONSE. Smoking rates are indeed declining much faster in countries where vaping is more popular.

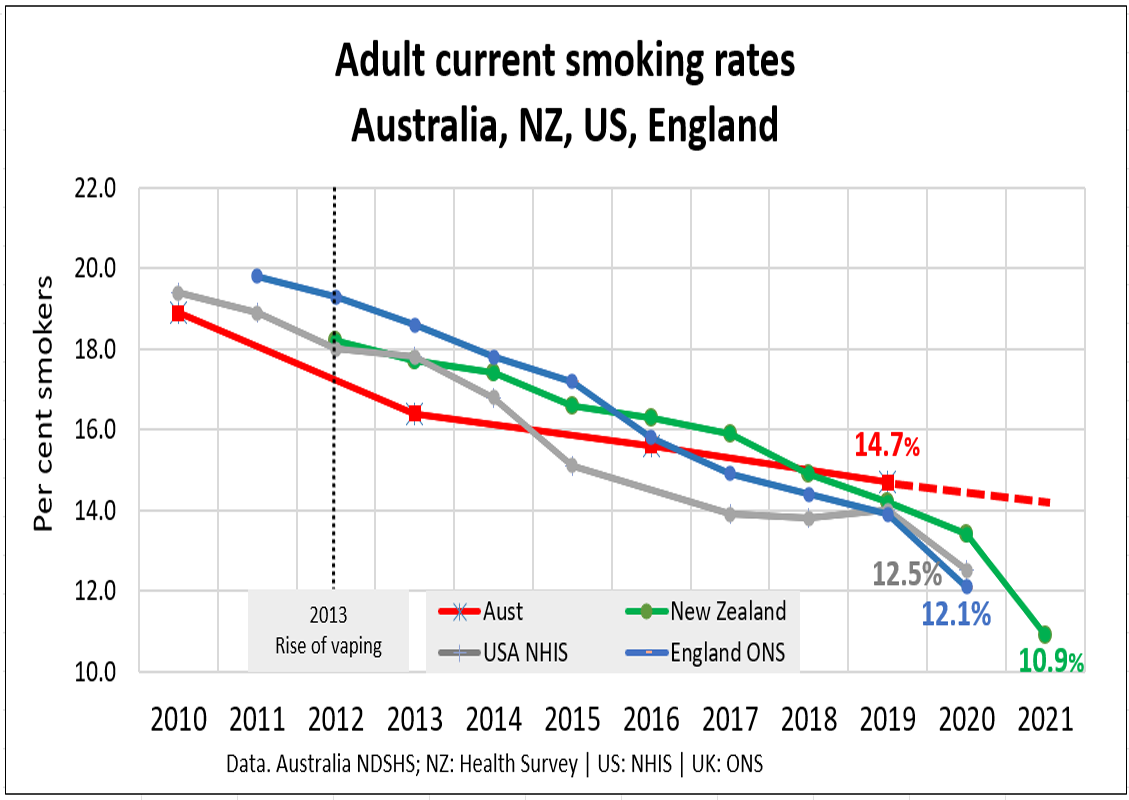

In Australia, the rate of decline in adult smoking was 0.3% per year from 2013-2016, in the United Kingdom 0.7% per year (2013-2019) and in the United States 0.8% per year (2013-2020). (Figure 1)

After vaping was legalised in New Zealand in 2020, there was an unprecedented 20% decline in adult smoking rates in the following 12 months (2020-21) as more smokers switched to vaping.

Figure 1. Countries with higher vaping rates have a faster decline in adult smoking

9. CLAIM: VAPING IS NOT A GATEWAY TO SMOKING

RESPONSE. Professor Chapman is confusing association with causation. Just because some young people start vaping and later go on to smoking does not mean the vaping caused the smoking. The most likely explanation is a common liability for risk taking, that is, young people who experiment with vaping are more prone to take risks such as smoking, drink driving and taking illicit drugs.

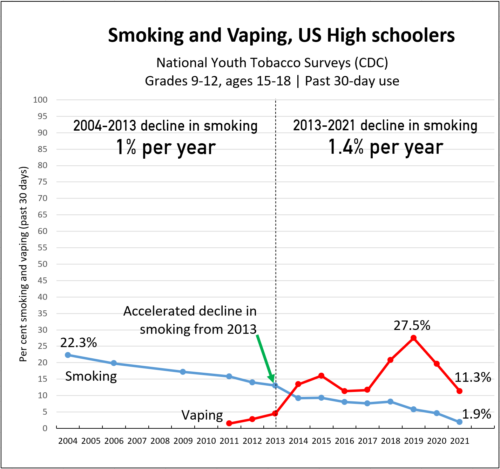

In fact, many studies now suggest that vaping more likely diverts young people from smoking than encourages them to smoke. Declines in youth and young adult smoking rates in the United States accelerated from around the time vaping became popular (Figure 2). This population finding is the opposite of that predicted by the gateway hypothesis.

Figure 2. Decline in youth smoking in US high schoolers

Furthermore, most young people who vape have first smoked cigarettes. Most vaping by never-smokers is experimental and transient, and regular vaping is rare.

10. CLAIM: BIG TOBACCO REALLY WANTS TO GET OUT OF SMOKING

RESPONSE. For over a century, tobacco companies have run an incredibly lucrative cartel, selling an addictive product and would prefer to continue the status quo. However, vaping and other safer nicotine products pose an existential threat to the industry so that it faces a potential Kodak moment. Introducing safer alternatives is a commercial decision, but it is also beneficial to public health.

Thirty per cent of the gross revenue of the world’s largest traded cigarette company Philip Morris International is now derived from reduced-risk products and other tobacco companies are also making the transition away from combustibles. If Big Tobacco makes fewer cigarettes and more reduced-risk nicotine alternatives, that has to be a good thing.

Go to Top