NICOTINE POUCHES are becoming popular as safer nicotine alternatives to smoking tobacco in other countries. Are they legal in Australia? Are they safe? Where can you buy them?

Nicotine pouches are small bags of nicotine (in various doses) that are placed between the upper lip and gum for about an hour, and steadily release nicotine. They do not contain tobacco and are used as a safer substitute for smoking. Vapers also use them to provide nicotine when it is not convenient to vape or when extra nicotine is needed.

Interview on GFN.News, April 2024

How are nicotine pouches regulated in Australia and do you need a prescription to purchase them?

In Australia, nicotine pouches are a prescription-only medicine, like vapes. There are two legal ways to legally purchase them

- Firstly, from a pharmacy with a prescription. However, I am not aware that any pharmacies sell them.

- Or they can also be imported from overseas, with a prescription.

Most regular adult users import pouches from overseas websites. Some have prescriptions, but most don’t and some orders do get intercepted at the border.

There are only a small handful of GPs that prescribe them.

Are health authorities concerned about the illegal sale of nicotine pouches in Australia?

Pouches can also be purchased illegally from local retailers, tobacconists, Australian websites and on social media. There are reports of influencers promoting them online.

There are penalties of up to 5 years imprisonment and fines of up to $120,000 for illegal sales or advertising.

There has recently been a media frenzy mainly around the potential uptake of pouches by young people and fears that young people will be attracted to the flavours and become dependent on nicotine. However, there is no evidence of youth uptake sofar.

Nicotine pouches are marketed as tobacco-free and do not contain tobacco, so what are the health risks?

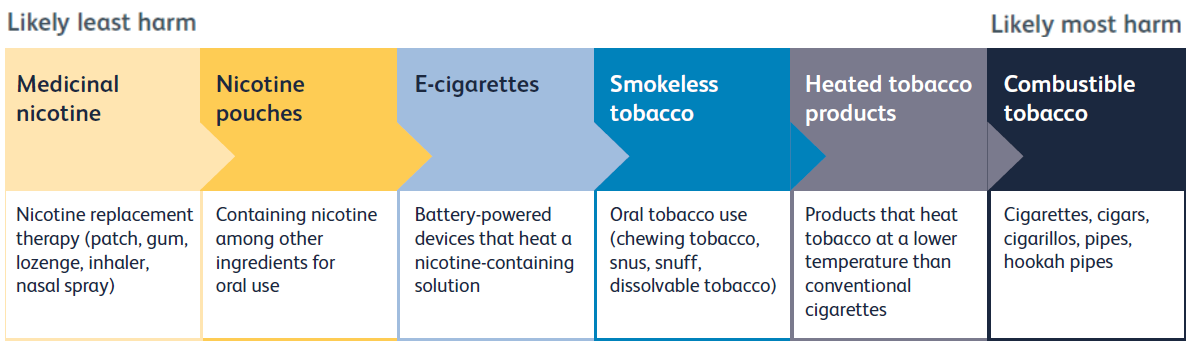

Pouches are very low risk products. They contain nicotine, plant fibre, sweeteners and flavourings. There is no tobacco and no combustion. There has not been much safety research, but we know that the risks from snus are very small and pouches are rated as even safer than snus and vapes.

If nicotine pouches are safer than combustible cigarettes, why does the Australian government want to ban them?

There are no plans to ban pouches at the moment, but their use is discouraged and access is restricted.

The policy on pouches reflects the abstinence-only ideology for nicotine in Australia, and particularly concerns about youth access.

Do we see any evidence that the use of nicotine pouches is on the rise in Australia?

There is a small group of regular adult users in Australia which is increasing. Google trends shows an increase in searches about them.

Almost all use is by adult smokers or former smokers as a quitting aid. They are also used by vapers as an alternative when vaping is inconvenient or as a way to cut down on vaping.

Is there any research exploring the relative risks of nicotine pouches in Australia?

There is no Australian research and very little overseas. However, experts have ranked pouches as substantially safer than smoking and even safer than vaping.

Pouches would be even less harmful than snus as they do not contain tobacco. With modern snus, there is no significant increase in cancers, cardiovascular or respiratory disease.

Do you think that nicotine pouches are going to become more and more popular across Australia, and are fears around their popularity with young people justified?

There will always be a market for pouches and the number of users is slowly increasing.

We know snus is an effective quitting aid and there is every reason to believe that pouches will also be effective as they give good nicotine delivery.

Pouches are more popular than snus in Australia. Snus does not need a prescription but it is very expensive. There is a tobacco tax of $2,000 per kg including GST, which is prohibitive for many users.

There is no evidence of youth use of pouches so far and I think the risk of any significant youth uptake is very unlikely, especially among non-smokers.

For more information

Kozlowski LT. Nicotine Pouch Use is on the rise. ThinkGlobalHealth 2022

Facebook group: Snus Aficionado’s Australia

THIS WEEK I GAVE EVIDENCE to the NSW Parliamentary Inquiry into vaping. However, I was appalled by the false and misleading information provided to the Committee in anti-vaping submissions and oral evidence by experts whose advice has created the current regulatory disaster. Continuing to follow this flawed advice will only lead to further harm to public health.

Rampant misinformation

I was shocked by the pervasive misinformation provided to the Inquiry from supposed experts who should know better. Some of the most egregious and misleading arguments are listed below, with my responses in brackets:

- That vaping is a gateway to smoking [response]

- Vaping is increasing smoking in youth [response]

- Vaping is as harmful as smoking [response]

- Nicotine harms the adolescent brain [response] and causes seizures [response]

- Vaping nicotine causes EVALI, a serious lung condition [response]

- We just need to expand enforcement to eliminate the black market [response]

- Vaping has limited evidence of efficacy [response]

- Vaping is a threat to tobacco control and is a public health crisis [response]

- A ban will protect young people from vaping [response]

- Vaping is a tobacco industry plot [response]

- The NHMRC and ANU reports are accurate reviews of the evidence [NHMRC response] [ANU response]

My evidence

I gave evidence at the Hearing on 12 April 2024 ⤵️

➡️ My written submission is available here.

➡️ Here is my introductory speech at the Hearing:

“Australia’s policy on vaping is driven by valid concerns about harm to young people. However, we need to balance the small harms to young people against the substantial benefits of vaping in reducing death and disease from smoking. Modelling studies consistently show that vaping has a positive impact on public health overall. [link] Regulation should reflect that.

The current restriction of vaping amounts to prohibition, and drug prohibitions are rarely successful. [link] Vaping is so harshly restricted that 90% of users don’t comply. This has predictably

- Created a thriving and dangerous black market controlled by criminal gangs with serious, escalating violence

- Resulted in the vast majority of products are unregulated

- Made it much easier, not harder, for young people to access vapes

- Reduced legal access by smokers who need vaping to quit

History has shown that [link]

- Enforcement and border control efforts have minimal impact on the supply of drugs

- The only way to significantly reduce a black market is to replace it with a legal, regulated one

The NSW Parliament must decide whether to allow the current failed model to continue under criminal control or to take control and regulate the market

The best way forward is to make vapes available as adult consumer products from licensed retail outlets with strict age verification like cigarettes and alcohol. [link] This will bring Australia into line with other Western countries.

It will reduce youth access, enable legal access for adult smokers, and reduce the black market

The Committee’s dilemma

Past experience with Parliamentary Inquiries into vaping suggests that Committee members vote along Party lines that are pre-determined before the Inquiry.

However to make rational decisions, Committee members rely on honest, accurate and unbiased evidence from experts. Making an accurate assessment is not possible if the Inquiry is flooded by false testimonies driven by ideology and vested interests.

We can only hope that the Committee members stop taking advice from the supposed experts whose advice has created the current failed scenario. More of the same will lead to disastrous consequences for public health.

Resources

Video recording, Hearing Day 2, 12 April 2024. [Credits Pippa Star, Hudson Orr]

THE CURRENT SENATE VAPING INQUIRY is a real opportunity for change policy. There is growing support for vaping reform in federal Parliament. We think a majority of senators understand that the current model has failed. The deadline for submissions is COB 12 April 2024.

The vaping bill before parliament is intended to ban “the importation, domestic manufacture, supply, commercial possession and advertisement of vaping goods”. Overall, the goal is to reduce youth vaping and provide prescription access for adult smokers.

However, this model will fail even with the final proposed changes. It has fuelled youth vaping, failed adult smokers and created a thriving and dominant black market controlled by criminals. See here for more

A better approach is for the bill to be amended to an adult consumer framework with strict age verification, with vapes sold like cigarettes and alcohol.

Here are some thought starters to assist in preparing your submission. It is best to be concise and keep your submission brief, no more than several pages.

Introduction

Start by briefly describing who you are and the difficulty you had quitting smoking. Explain how vaping helped you quit and how it has benefited your health and finances.

The current model is not working

Explain why, in your opinion, the current prescription-only model is not working, and why it will not work even with modifications and further enforcement. Reasons could include

- Few doctors provide nicotine prescriptions or support for vaping. Is your doctor willing and able to prescribe nicotine?

- Getting a script is costly and difficult

- Very few pharmacies stock products that have helped you quit. Are there any suppliers near you?

- Why you think vapes should be a consumer product (like cigarettes), not a medicine or “therapeutic product” requiring a prescription

- How flavour restrictions may affect you

- Are you at-risk of going back to smoking?

- Do you think vapers will follow the restrictions (be careful not to incriminate yourself)

- Your concerns about being able to access safe, regulated vaping products under the current model

- The current model has fuelled youth vaping. This is the direct result of the black market

- Your concerns that criminal gangs have taken over the market, creating a frightening crime wave (firebombings, murders, extortion)

- History shows prohibition never works. Illegal products will still enter the country and the black market will just go underground. Enforcement and policing are ineffective.

Better regulation

Discuss why a different regulatory framework would work better. For example, under New Zealand’s model, nicotine vapes are sold as adult consumer products from licensed retail outlets with strict age verification. Vape shops can provide expert advice, support, and a wider range of products. Licensed retailers are unlikely to sell to kids if there is a risk of losing their licence and paying large fines. There is no significant black market in New Zealand.

- Why would this model be better for you? Would it give you better access to safe, regulated, approved products?

- How would it reduce youth vaping and the black market?

- How would it help the economy, providing employment and tax revenue?

- Why the government should support adult smokers, not just focus on youth vaping

- Vaping should be at least as easy to access as deadly cigarettes

- Your human right to choose a safer alternative to smoking to improve your health

Making your submission

The deadline for submissions is Friday, 12 April 2024.

Here is the committee’s inquiry page for more information: Therapeutic Goods and Other Legislation Amendment (Vaping Reforms) Bill 2024 [Provisions] – Parliament of Australia (aph.gov.au)

Submissions can be lodged online or via email.

SPEAKERS IN LAST WEEK’S PARLIAMENTARY DEBATE on the Vaping Reform Bill all agreed that the primary focus of vaping legislation should be to reduce youth use. However, there was very little agreement on anything else. The debate uncovered widespread misinformation about vaping and largely dismissed the huge value of vaping as an adult quitting aid.

Single-minded focus on youth vaping

The focus of the debate was almost exclusively vaping by young people. This concern is legitimate but was disproportionate given the low rate of regular or frequent youth vaping. Only 3.5% of Australian 14-17-year-olds vape daily. Most youth vaping is infrequent and transient and is of little public health importance. Half of those who vape do so only once or twice. MPs seemed unaware that vaping is diverting young people away from deadly smoking and reducing smoking overall. Only 0.9% of 14-17-year-olds smoke daily.

Concerns about the harm to youth from vaping were also greatly exaggerated. Youth vaping is far from being “An unparalleled, unprecedented public health crisis affecting the young people of Australia”, as claimed by Dr Monique Ryan (Ind). Our recent Evidence Review concluded, “Youth vaping carries relatively minor health risks”. Vaping is one of the least risky risk behaviour that teens adopt, compared to smoking, binge drinking, and illicit drugs.

On the other hand, the substantial contribution of vaping in decreasing smoking among adults was disregarded. Zaneta Mascarenhas (ALP) and Dan Repacholi (ALP) even maintained that vaping “products threaten to undo much of the progress that we have made” in tobacco control. In fact, they are having the opposite effect ie accelerating the decline of smoking. As Pat Conaghan (NP) noted, “The countries that have made vapes more difficult to access than cigarettes have seen a considerably slower smoking quit rate than the other countries”.

Some MPs even claimed that vaping was not an effective quitting aid (it is actually the most effective and most popular quitting aid). “Vaping is not helping people in our community get off smoking” said Louise Miller-Frost (ALP). Dr Mike Freelander (ALP) claimed that there was no evidence that vapes are effective quitting aids and that they minimise harm.

Widespread misinformation

The level of misinformation from our elected representatives on this subject was appalling.

Labor MPs mostly repeated the talking points about youth vaping from Mark Butler, falsely claiming that vaping is a gateway to smoking, that smoking rates are rising in the under 25s (they are falling rapidly), and that vaping is creating a whole new generation of nicotine addicts (only 3% of teens may be nicotine-dependent).

Several MPs including Dr Mike Freelander (ALP) and Tanya Plibersek (ALP) falsely claimed that vaping kills (there has never been a confirmed death from vaping nicotine anywhere). “Their use as a smoking deterrent simply results in swapping one damaging habit for another” said Zoe Daniel (Ind), apparently not realizing that vaping is a valid form of harm reduction and that switching leads to a huge reduction in risk.

Dr David Gillespie (NP) incorrectly linked nicotine vaping with the deadly lung disease, EVALI, which was due to vaping contaminated, black market cannabis vapes. Many asserted that vaping harms the adolescent brain, a claim for which there is no human evidence.

Labelling vapes as a tobacco industry ploy was another popular but incorrect claim. “Make no mistake; it is big tobacco that is behind the vaping industry”, said Zali Steggall (Ind). Actually it’s not.

Many listed the chemicals in vapour without seeming to understand that “the dose makes the poison”. Most chemicals in vapour are at very low doses and are below the threshold of harm.

Where is the genie?

There was disagreement about the location of the genie. Most Coalition and some independent MPs agreed with Dr David Gillespie (NP) that “The genie really is out of the bottle, and it is pretty much impossible to put it back in”.

However, ALP speakers seemed convinced that it was not too late. “This legislation to curb vaping is our opportunity to … put the genie back in the bottle” said Louise Miller-Frost (ALP).

Failure of the current model

Speakers from the Coalition argued that the current prohibition model of regulation has failed and that change is needed. Youth vaping has escalated, vapers have rejected the prescription model and criminal gangs control the market.

Pat Conaghan (NP) pointed out that “more than 1.5 million people in this country are currently purchasing unregulated vapes via the black market…run by organised crime syndicates”. “We’ve seen serious escalations of turf wars from organised crime groups, including personal violence and firebombings of tobacconist stores”.

David Littleproud (NP) said “History has shown for generations that prohibition doesn’t work, particularly when you’ve got a marketplace that has exploded.” “If we keep doing the same thing we will get the same outcomes” said Dr David Gillespie (NP).

The Liberals agreed. Dr Anne Webster (Lib) said, “The government’s prescription model is failing, and they are simply doubling down and banning vaping harder.” We “want this bill thoroughly examined by a Senate committee, and we will be moving to do just that” she said.

Amendment by the Nationals

In response to the failings of the current approach, Pat Conaghan (NP) proposed the following amendment to the Bill on behalf of the Nationals

“That the House

- Criticises the Government for failing to control the illicit vaping market and failing to protect children against the proliferation of vaping products that have exploded in availability through a black market driven by organised crime;

- Expresses its alarm that the current prescription-only model is failing, with only approximately 10 per cent of vapers purchasing their product legally through prescriptions;

- Acknowledges the existence and strength of the $1 billion black market vape trade in Australia, which is fuelled by the importation of more than 100 million illicit disposable devices each year;

- Recognises that resourcing of enforcement measures at the borders and the point of sale has been grossly insufficient and that policy measures such as prohibition have historically not worked;

- Calls on the Government to consider all policies to prevent children from accessing and becoming addicted to vaping products; and

- Further criticises the Government for failing to establish or fund its promised illicit tobacco and vaping commissioner”

The way forward

The Nationals support “regulation and taxing of government-approved nicotine vapes following the same general principles as alcohol and cigarette sales. That includes licensed retail outlets, supply chains, and strict age verification” according to Michael McCormack (NP). Anyone who thinks we can control this by policing and Border activity “are just seriously kidding themselves” he said.

David Littleproud agreed. “To think that we’re going to be able to crack down and stop all this at the border is naive. It won’t happen”. Furthermore, “A regulated model will work and gives us a better chance at protecting children.”

This model is found “across the EU, including in Sweden, and in other comparable western countries, such as the UK, the USA, Canada and New Zealand” said Pat Conaghan.

However ALP speakers were convinced that simply getting tougher and banning harder to bring things under control. They maintained that increased border control and policing would constrain the illicit market, and that vapers would suddenly start getting prescriptions. How this will happen remains to be seen. Market research has found that vapers will still refuse to get prescriptions if further restrictions are introduced.

Helen Haines (Ind) believes that “With this bill adopted, the only vapes available legally in this country from 1 July would be those prescribed by medical practitioners and dispensed by pharmacies”. If only it was that simple. Most criminologists would not agree with her.

The reality is that “Law enforcement and border control efforts have minimal long-term impact on the supply of drugs in the community”, according to a 2023 report on vaping by Australian health consultancy group, 360Edge.

Senate Inquiry

The future of this legislation will be decided by a Senate Inquiry. Submissions are being accepted to this Inquiry until 12 April and it will report on 8 May. Further information is available here.

The committee must decide what is the best regulatory method for Australia: to continue with the failed prohibition model or to move to an adult consumer model and regulate vapes like cigarettes. Submissions should focus on that issue.

References

Therapeutic Goods and Other Legislation Amendment (Vaping Reforms) Bill 2024

Hansard

Mascarenhas, Littleproud, Neumann, Daniel, Repacholi, Haines

Amendment

Amendment to the motion by Mr Pat Conaghan MP, 27 March 2024

MARK BUTLER HAS INTRODUCED his vaping Bill to Parliament. If I were a member of Parliament, I would oppose the Bill. The current regulatory model has failed and will only get worse with the proposed changes. Here are 7 reasons why a new approach is needed.

1. Youth vaping has skyrocketed

The current illegal markets make it easier, not harder, for teens to access vapes, because there are no restrictions on who can buy them. Underage users have easy access to unlabelled, high-nicotine, unregulated products. One in ten 14-17-year-olds in Australia are currently vaping, and the number is rapidly increasing, creating alarm for parents and teachers. Vaping is much less harmful than smoking but it is not risk-free. There is concern about young people developing nicotine addiction.

2. Control by criminal networks

Australia’s de facto ban has handed control of the vaping market to criminal networks. Ninety percent of adult vapers purchase their products from illegal sources. This has led to an escalating turf war with nearly 60 firebombings of tobacco and vape shops so far, public executions and extortion. Organised crime groups are recruiting vulnerable kids to commit crimes.

Minister Butler says the black market for vapes is” funding the criminal activities of organised crime gangs, drug trafficking, sex trafficking and the like”.

History has shown that intensive enforcement and border control efforts have minimal long-term impact on the availability of drugs in the community if demand is strong and controls are easy to overcome.

3. Loss of commerce and revenue

Under the current Bill, the legal retail vape and manufacturing industry will be forced to close, leading to loss of employment and bankruptcies.

However, a legal vaping industry will generate substantial economic benefits. These include a taxation windfall, substantial savings in healthcare and compliance costs, reduced GP visits and reduced smoking cessation treatment costs.

It will also stimulate the economy and create manufacturing and export opportunities. A report from the UK below outlines the financial benefits.

For more:

Why vaping reform in Australia makes economic sense. Blog 13Nov2023

CEBR report for UKVIA Economic impact assessment of the vaping industry. September 2022

Independent Economics. Tobacco & vaping in Australia. An updated economic assessment. March 2023

4. It has failed adult smokers and vapers

The current policy makes it much harder for adult smokers to legally access a far less harmful alternative to smoking than to purchase deadly cigarettes. Very few doctors are willing to prescribe nicotine liquid and only a handful of pharmacies are willing to dispense it. However, cigarettes are available from up to 40,000 retail outlets.

This pathway is onerous and costly for patients and has been rejected by over 90% of adult vapers. It undoubtedly means that some smokers will continue smoking instead of switching to the safer alternative.

5. Unregulated products

Australia has quality and safety standards for legal vaping products (TGO 110). However, under the current regulatory model, 90% of products are supplied by the black market and are completely unregulated, exposing users to greater risk.

6. A lost opportunity for public health

Vaping is the most effective and most popular quitting aid for smokers. In countries where vaping is readily accessible, the decline in smoking rates is faster than in countries like Australia where access to vapes is difficult.

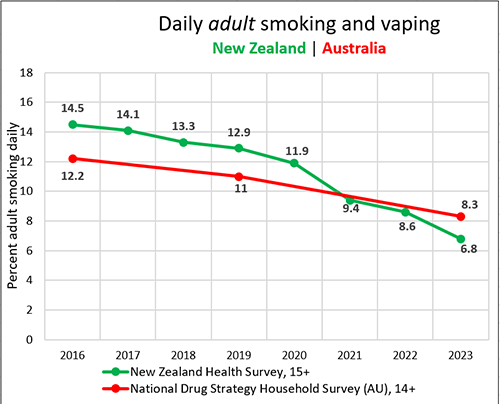

In New Zealand, for example, adult smoking declined by an unprecedented 53.1% from 2019-2023 and the decline has been greatest in the younger adult age groups with the highest vaping rate. In Australia, smoking declined by 25% during the same period. At least some of this decline appears to be due to illegal vapes replacing smoking.

Modelling studies have estimated that the overall public health benefits of vaping are considerably greater than the risks, even when modelling the impact of an increase in youth vaping.

7. Public support

The Australian public does not support the current prohibitive approach. A recent Redbridge Survey found that 84% of adults agree/strongly agree that “Nicotine vaping products should only be available through licensed retail outlets to adults”.

Conclusion

The reality is that vaping is here to stay whether we like it or not and it needs to be regulated better.

A better regulatory model is for nicotine vaping products to be sold as adult consumer products from licensed retail outlets with strict age verification, like tobacco and alcohol. This will gradually eliminate the black market, reduce access for youth, provide regulated products for adult smokers and generate tax and other revenue.

Public health policy should be based on a population risk-assessment. A more evidence-based, harm reduction approach which is proportionate to risk will lead to better outcomes for public health for the whole population, at no cost to the public purse.

References

Therapeutic Goods and Other Legislation Amendment (Vaping Reforms) Bill

Explanatory Memorandum

THE VICTORIAN PARLIAMENT INQUIRY INTO VAPING can recommend legislative changes to end the current, failed prescription-pharmacy model that has handed control of the market to criminal gangs. The Victorian Parliament can and should replace it with a strictly regulated adult consumer model.

Please make your submission before the deadline next week, on Friday 29 March 2024.

My submission

My submission to the Inquiry can be accessed here. The executive summary states:

“Smoking is the leading preventable cause of death and disability in Victoria and is a leading cause of financial inequality. Vaping is the most popular and most effective quitting aid available and has the potential to substantially reduce smoking rates and improve public health.

The current prohibitive, prescription-only, regulatory model for nicotine vaping products (NVPs) has failed to achieve its goals. It has been rejected by doctors, pharmacists, and the general public and has helped create a thriving illicit market controlled by criminal networks. The illicit market supplies 90% of the vaping market with unregulated products and sells products freely to young people. It has led to escalating criminal activity.

An evidence-based approach to vaping policy is to make nicotine vaping products available as adult consumer products sold from licensed retail outlets with strict age verification, like tobacco and alcohol, as is the case in all other Western democracies. This will enable adult smokers to legally access regulated products, reduce access to young people, largely eliminate the illicit market and criminal activity, and generate appropriate taxation returns.

Vaping is here to stay whether we like it or not. 430,000 Victorian adults now vape and the number continues to increase. The Victorian Parliament must decide whether to allow the current failed model to continue under criminal control or to take control and regulate the market. Public opinion is strongly in favour of regulating NVPs like tobacco and alcohol.

The Victorian Parliament can make legislative changes to allow this regulated model to replace the current failed policy.”

The terms of reference

The Inquiry is focused on four issues. You can respond to one or more of these.

- Trends in vaping and tobacco use and the associated financial, health, social and environmental impacts on the Victorian community

- The causes and repercussions of the illicit tobacco and e-cigarette industry in Victoria including impacts on the Victorian justice system, and effective control options

- The adequacy of the State and Commonwealth legislation, regulatory and administrative frameworks to minimise harm from illicit tobacco and e-cigarettes compared to other Australian and international jurisdictions

- The effectiveness of current public health measures to prevent and reduce the harm of tobacco use and vaping in Victoria and potential reforms

Submissions can be uploaded here.

My submission

Mendelsohn CP. Submission to Victorian Parliament vaping and tobacco inquiry 12March2024

MORE THAN THIRTY AUSTRALIAN tobacco control and addiction experts wrote today to Mr Peter Dutton, leader of the federal Opposition, in support of his comments on vaping regulation.

In a recent interview on 2DayFM, Mr Dutton acknowledged that the current regulatory model is not working and supported regulating vapes like tobacco products. As a former police officer, he is very aware that “When we have banned things in the past, alcohol… it doesn’t work”.

Interview on 2DayFM with Peter Dutton

Mr Dutton will face intense opposition from Australia’s Public Health lobby which embraces the failed prescription-pharmacy model.

However, his view is supported by many Australian and overseas experts and is consistent with best practice

This week, the federal Parliament will debate Mark Butler’s controversial vaping Bill which aims to restrict vaping even further. It is expected that the Liberals, Nationals, PHON, and some independents will vote against the Bill.

The Bill will be rejected if the Greens oppose it, however, the federal Greens have not yet announced a position on vaping. The NSW and Tasmanian Greens have publicly supported legalisation and regulation of nicotine vaping products as adult consumer products.

The letter

The letter to Mr Dutton [available here] outlines how Australia’s de facto ban has handed control of the vaping market to criminal networks and has led to an escalating wave of criminal activity. The illicit market also sells freely to youth.

Less restrictive access to e-cigarettes in the United Kingdom and New Zealand has been associated with accelerated declines in smoking and improved public health outcomes.

In New Zealand, for example, adult smoking declined by an unprecedented 53.1% from 2019-2023 and the decline has been greatest in the younger adult age groups with the highest vaping rate. In Australia, smoking declined by 25% during the same period and some of this decline is due to illegal vapes replacing smoking.

An overwhelming majority of the Australian public also supports this approach. A recent Redbridge Survey found that 84% of adults agree/strongly agree that “Nicotine vaping products should only be available through licensed retail outlets to adults”.

The tide is turning

Opposition to the current medical model is growing with increasing support in Parliament. Two recent articles in The Australian [here and here] by health editor Natasha Robinson have provided strong support, concluding

“Australia stands on the brink of a public health disaster. The failure to regulate vaping in the past three to four years has created an illicit disposable vapes market that is rampant and looks to be impossible to stamp out. Vaping rates have exploded despite disposable vapes being made illegal. Organised crime controls the trade, lured by massive profits.”

Resources

Letter to the Hon Peter Dutton MP, 19 March 2024

I WANT TO LET EVERYONE KNOW that I am back at work. After trying to retire twice, I have found that vaping advocacy is more addictive than I thought.

Professor Ron Borland calls me the Dame Nellie Melba of Tobacco Harm Reduction for my failed retirement efforts. Dame Nellie (pictured above) was a famous Australian soprano who is remembered for her “seemingly endless series of ‘farewell’ appearances in the 1920s”.

Part of my motivation is selfish. I get enormous satisfaction from seeing smokers make the switch to vaping. Vaping has the potential to save the lives of millions of people. I can’t think of many things more worthwhile for public health than vaping advocacy.

And I do think our advocacy is working despite powerful opposition. There is every chance that Mark Butler’s flawed vaping Bill will be rejected in the Senate later this month.

Why we will win…

Mr Butler wrongly believes that he can force vapers into compliance by increasing enforcement and policing for his prohibitive approach. However, experience has shown that:

“Enforcement and border control efforts have minimal long-term impact on the supply of drugs in the community. In fact, when substances are banned, suppliers find more creative ways to hide and sell their products, which leaves the buyer at a higher risk of buying unsafe, unregulated products of unknown quality and potency” (Australian Health consultancy group 360Edge)

Alcohol prohibition in the US “was a failure on all fronts”. Criminal syndicates controlled the market and thrived. It led to disastrous health consequences with deaths from alcohol poisoning and overdoses from dodgy alternatives. Many drinkers switched to dangerous alternatives such as opium and cocaine.

The “War on Drugs” has failed to reduce illicit drug supply and use. It has serious consequences including criminalising users; huge policing and enforcement costs; tainted and impure products; increased drug potency causing overdoses and poisonings; higher prices; violent gang wars and deaths; corruption; and incarceration.

Increased violence is an inevitable consequence of drug prohibition. This is clear from from Australia’s vaping ban which has led to an escalating cycle of intense criminal activity, drug wars, firebombings, extortion, and public killings.

Bans also violate the human right to the best possible health and are a social justice issue, harming people from marginalised and disadvantaged populations most of all.

On the other hand, regulation of vaping can reduce risk by enforcing quality and safety standards. The black market will diminish if easy access to legal products is available. Licensed retail sales will also reduce youth access, as for tobacco and alcohol.

What YOU can do

One of my greatest frustrations is the lack of active engagement of Australia’s 1.7 million vapers in fighting for their rights. Vapers are passionate about vaping, but only a small number are actively advocating for change in Australia.

However, regulation of vaping is a political decision and politicians in a democracy are strongly influenced by the views of their constituents. Enough adults vape to have an enormous influence over policy-making and you need to be heard.

Some things you can do are

- Join the Australian Smokefree Alternatives Consumer Association (ASACA), the consumer advocacy group

- Write to or visit your federal member of Parliament and Senators, explaining why vaping is so important to you and how it has improved your health

- Contact your state MPs, as change can still come from state governments

- Contact the media via radio or print whenever an opportunity arises

Mark Butler’s flawed prohibitive model will fail, but in the meanwhile it is doing enormous damage to public health. The sooner it is changed the better.

AFTER HEALTH MINISTER BUTLER has repeatedly promised that he is “not going after” people who vape, especially young people”, a thirteen-year-old boy was arrested by NSW Police recently.

The boy was with his mother in the NSW country town of Deniliquin on 27 February 2024 and was asked to hand over his vape. Of course, he should have followed the police’s instructions. When he rudely refused, the two police officers carefully dropped him to the ground and presumably arrested him.

Video available at https://twitter.com/BradK87287/status/1764618414906347860

The boy was arrested and taken to Deniliquin Police Station to confirm his identity before being released without charge. Reports say he will be dealt with under the Young Offenders Act.

YouTube would not allow me to upload the video as it “violates their child safety policy”. YouTube doesn’t allow content that endangers the emotional and physical wellbeing of minors.

Under NSW law, police can confiscate a vape if they think you are under 18. However, this is precisely what Mark Butler has promised will not happen.

Events like this highlight one of the many unintended consequences of Australia’s de facto prohibition of vaping – criminalising people who vape

It puts otherwise law-abiding people in contact with police and the judicial system, with the potential for a criminal record and all the potential repercussions of that. As with other illicit drugs, the people most likely to be affected are those from disadvantaged and lower socio-economic groups.

In some jurisdictions, possession can also result in jail time.

Other consequences of the prohibition of vaping include

- Criminal activity, gang wars

- Unregulated products, sold to children

- Increased smoking

- Increased drug potency and contamination

- High costs for policing, border control, prisons, judicial system

- Loss of government revenue

Furthermore, there is a long history demonstrating that prohibition is not effective in reducing the supply and distribution of illicit drugs

In Western Australia, an adult vaper was charged with possessing vape liquid recently after police found a vape in his car, despite Mr Butler’s reassurance that this would not happen. The 49-year-old man could be jailed and fined for this offence.

Australia’s other 1.7 million vapers appear now to be at similar risk for not complying with the government’s unworkable nicotine prescription regulations. According to the recent 2022/23 National Drug Strategy Household Survey, 87% of vapers do NOT have a nicotine prescription.

Mr Butler needs to urgently explain why these cases are occurring after his repeated advice that vapers will not be targeted.

TODAY I HAD THE PLEASURE OF speaking with one of Australia’s leading experts in tobacco control, Dr. Colin Mendelsohn. With over three decades of dedicated service in smoking cessation and tobacco harm reduction, Dr. Mendelsohn’s expertise is both rare and invaluable. In our discussion, we delve into the complex world of public health, examining the often unnoticed echo chambers, the intricate web of incentives that shape government policies, and the impact of societal and governmental biases on public health decisions.

This episode is more than just a talk on tobacco control; it’s a lens to try to understand the authoritative landscape of Australian and public health in general, exploring alternative approaches and addressing solutions on a global scale.

Our conversation culminates in a crucial discussion about the importance of being open to evidence in public health, particularly in tobacco and smoking control. Dr. Mendelsohn, with his focus on harm reduction, provides a unique perspective on this issue, advocating for the use of safer nicotine products like vaping and smokeless tobacco for those who struggle to quit smoking.

Whether you’re a non-smoker intrigued by the complexities of public health or a smoker seeking safer alternatives, this episode promises to challenge some of your understanding of nicotine, tobacco and solutions in public health.

Robert Anton Patterson

Leafbox Podcasts

www.leafbox.com

Also available at

https://www.leafbox.com/interview-dr-colin-mendelsohn/

Apple Podcast @ https://apple.co/3v2d9B7

Spotify Version @ https://open.spotify.com/episode/0VNr53cO4mLwZ8BBqyHbNK?si=1b71da37299a40bc

Disclaimer: No Tobacco Company / Product Conflict of Interest

Neither Dr. Colin Mendelsohn nor I have any affiliations with tobacco control products or companies. Our discussion was conducted independently, without any commercial interests or influence from tobacco companies. The purpose of this discourse was solely to explore and debate potential public health issues, free from any commercial bias or conflicts.

Time Stamps

03:14: Biographical And Career Overview

06:14: Australian Tobacco Situational Overview

11:00 Discussion on “demonization” of Tobacco Users/Smokers

14:47 Uses cases for nicotine , understanding users

18:07: Ideological Issues + Biases in Australian Public Health

22:23: Discussion on Australian Authoritarian / “Nanny State” Public Health

25:25 Nicotine Prescriptions + Taxes Effects / Black Market Forces

32:32 Harm Reduction Model for Nicotine / Tobacco Control

36:08 Discussion on Vaping / Flavor Additives / Children’s Issues

41:06 China / Smoking vs Vaping in China / India

44:09 Smoking Cessation Tools

48:08 Marijuna Vaping vs Smoking

50:27: Discussion on Conflicts of Interests

54:56 Maintaining Openness to Evidence / Avoiding ideological silos

01:00:47 Discussion on Polarization / Disinformation / Information

01:06:00: Closing Remarks: Importance of quitting smoking and exploring safer alternatives.

More Information:

Dr Mendelsohn’s “Farewell Retirement Letter” Referenced in Conversation

X / Twitter: @ColinMendelsohn

More Info @ https://colinmendelsohn.com.au/

Founding Chairman, Australian Tobacco Harm Reduction Association charity

Book: Stop Smoking Start Vaping

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:00:00):

Things are very polarized. You either believe in it or you don’t. And if you believe in it, you don’t listen to the people who say that there’s a problem and vice versa. So people are in their little silos and they’re not listening to each other. We all feel very strongly about it, and that’s a problem. I think sites shouldn’t work that way. Sites should be about asking a question, gathering information and coming to a consensus. But there are all sorts of other emotional, ideological, personal issues and goals. People make up their minds about something and it’s very hard to get into change. Yes, it’s made me more sinal made me look at the issue or carefully than just accept what

Leafbox (00:01:07):

Today I had the pleasure to speak to one of Australia’s leading experts in tobacco control, Dr. Colin Mendelsohn, with over three decades of dedicated service and smoking cessation and tobacco harm reduction. In our discussion today, we delve into the complex world of public health, examining the often unnoticed created echo chambers, the intricate web of incentives that shape government policy and the impact of societal biases on public health decisions. This episode is more than just a talk on tobacco control. It’s a lens to try to understand the authoritative landscape of Australian public health. Our conversation culminates in a crucial discussion about the importance of being open to evidence. Dr. Mendelsohn, with his focus on arm reduction, provides a unique perspective on this issue, advocating for the use of safer nicotine products like vaping and smokeless tobacco for those who struggle to quit smoking. And whether you’re a non-smoker, intrigued by this topic or someone seeking safer alternatives, I promise that this will offer you a way to challenge your thoughts on nicotine, tobacco and public health.

Thanks for being here.

Colin. Before we start, congratulations on your retirement.

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:02:20):

One of the things, I haven’t actually retired, we might mention that, but I’ve tried three times and I just can’t send to let go. I keep going back to the work which I really enjoy, and I often think when I’m sitting around at home, what do I do now I retired, but what I really want to do is go and read some journal articles about smoking or vaping and write an article and maybe do some teaching and I just felt I keep slipping back into it.

Leafbox (00:02:47):

It’s funny because you’re a doctor and a public health advocate and I kept returning to your blog posts about your upcoming retirement. I think the tone is very strong and interesting to maybe start our conversation. But before we start there, could you give us a quick update of your career, your medical practice, what attracted you to smoking, what it’s like being a doctor in Australia, just a general overview of how you describe yourself.

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:03:14):

I became a medical practitioner in 1976. I graduated. My father was a doctor. My two brothers are doctors, so the cancer runs in the family as well as many other members of the family. I initially worked in general practice but became involved in a university smoking program. Within a few years I was asked to teach in this program and I just developed an interest in smoking as a result of that. But it’s very clear that in general practice and in medicine generally probably the most important thing you can do for someone’s health is to not look at smoking. I mean, we know smoking kills up to two in three long-term users and they lose on average 10 years of life. I mean, smoking kills over a billion people, it’s going to kill over a billion people. This century, 21,000 Australia die every year unnecessarily because of smoking.

(00:04:08):

It became clear that I was going to do something useful, then helping people quit smoking would probably be the most important thing I could do. But having said that, it’s one of the most frustrating things to deal with, not just for the patient who smokes but also for the doctor. I mean the success rates are very low. We know how addictive smoking is. And then in 2014, electronic cigarettes we came about in Australia. I became aware of them and I was seeing the results, hearing excellent reports. So I went to the UK in 2015. I spoke to some of the leading experts there that was the epicenter of vaping. Came back to Australia, wrote some articles and started following the research very closely, seeing wonderful results with my smoking patient. Now we know that it’s the most effective quitting aid we have to help people quit and it’s at least 95% safer for smoking.

(00:05:03):

So for people who can’t quit, it’s a no-brainer that you’re going to reduce your harm by making that switch. So I’ve been involved in research, teaching, advocacy, helping smokers to quit in 2017, small group of doctors and I started a health promotion charity called the Australian Tobacco Harm Reduction Association, which was all about raising awareness of products like vaping to help people quit smoking. And that was been running for some years. I became an associate professor in public health for several years. I’ve been on the committee that develops the Australian smoking cessation guidelines. So it’s been a special area of interest and I wrote a book about quitting smoking by switching to vaping or stop smoking start vaping if I could just make a small plug, which is all about giving people the evidence and practical advice on how to quit. So that’s been my career over about, well now, well too many years to remember. 24, no 48 years of medicine. Over the last few years I’ve focused almost exclusively on smoking and vaping.

Leafbox (00:06:14):

Could you give us a little bit of context on the Australian situation, the politics around vaping, about tobacco products, maybe in a contrast to the US and even China. Let’s just give a global overview of what tobacco products are like worldwide.

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:06:31):

Yeah, look, smoking is still a huge issue. It’s the biggest preventable course of death and illness in the world. So 1.3 billion smokers, people still smoke around the world and that hasn’t changed since about 2000 and there’s about 1 billion deaths globally. So it’s a huge issue. So just encouraging people to quit isn’t working. So that’s why alternatives like vaping have become popular. In Australia in particular, the smoking rates have remained stagnant for the last five years. They actually haven’t reduced number of smokers, any just smokers are much the same. Whereas in some countries like the US New Zealand, in the eu, in the uk, we’re seeing quite rapid falls in smoking rats and we can come back to that. But that’s mainly occurring in countries which have embraced tobacco harm reduction, which means tobacco harm reduction is kind of a pragmatic solution to smoking. It said, look, we know you can’t quit, but we don’t want you to die from it.

(00:07:39):

So if you have to quit, keep smoking, let’s switch you over to something safer that won’t kill you. It won’t eliminate all the harm, but it’ll eliminate most of the harm countries which are doing that which allow those products are seeing rabbit tools in smoking still, most of the smokers occur in lower and middle income countries and they’re the ones that are struggling most. They’re not getting the benefit of these safer alternatives. We can talk more about those safer alternatives, but there are countries where smoking is declining rapidly. For example, take our nearest day New Zealand. This is just a very similar neighboring country which has a very similar demographics and social economic qualities to Australia and it’s very similar tobacco control in New Zealand, the smoking rates fallen by 49% in five years and that’s because they’ve embraced vaping. So they’ve got massive numbers of smokers switching to this much safe alternative.

(00:08:37):

In Australia, we have hostile opposition to vaping. Smoking rate has remained unchained and the only difference between the two countries in terms of tobacco control and recent changes has been vaping. It’s clearly a factor in Japan, they have a different kind of safer alternative called heated tobacco where you use the little tobacco stick, you don’t burn it, you put it into an electronic device and heat it and you get a vapor. In Japan, consumption of tobacco has fallen by 50% in the last seven years, Sweden, in Sweden, they use little nicotine pouches that they put under the gum. Sweden has the lowest smoking rate in the western world, about 6% of the people smoke. They have incredibly low smoking related disease, the lowest lung cancer rate by far in Europe. So this is an alternative, a safer alternative to cigarettes. And lot countries are now introducing nicotine pouches, which are like sze again, little pouches that go under apple dip.

(00:09:44):

So there are ways to get these smoking rates down then they haven’t reached most of the low and mid income countries where they’re needed. And in Asia, smoking rates vary enormously and attitudes to these products vary enormously. For example, in the Philippine smoke of vaping is approved and it’s of course having success in Thailand, it’s not approved and it often seems quite random. There are all sorts of bizarre reasons why countries prove and don’t prove these alternatives to smoking. But one thing for sure is that they do work when they’re male vulnerable. The many countries see them as a threat for all the wrong reasons and we can talk about why they’re imposed. There’s a lot of misinformation about vaping, but where these products are available, they’re making any difference and without them we’re finding people are really struggling to get those smoking rates down.

Leafbox (00:10:36):

Well, and one of the things interesting about your book is that your tonality towards nicotine users is neutral. And I’d like to contrast that with maybe the general feeling in Australia that all nicotine products are evil or dangerous, and where do you think that bias comes from or what are the benefits of nicotine? Why do people use nicotine? Maybe you can explore some of those issues.

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:11:00):

Look, it’s not only nicotine, that’s evil, but smokers as well. I mean smokers have been victimized, they’ve been stigmatized, they’ve been labeled weak will deliberately of not doing what they’re being told to do and smokers being vilified like that. And that’s very distressing and really being able to, because most of them began when they were young, they became addicted and weren’t able to quit. So they’re compulsive in their habit and that’s just something that’s just developed over time. These days we tend to see smoking more as an addiction rather than it’s something that LPs control. Most smokers would deeply love to quit and it’s really unfair to demonize them because of it. They would love to quit. Most of them would. Many of them have given up because they just found it so hard. And the other issue you brought up is the whole issue nicotine.

(00:11:54):

Nicotine has also been really demonized over the years. It’s terribly misunderstood and that’s because it’s associated with smoking and it does cause dependence, but otherwise it’s relatively benign. That’s not just my view. I mean the Royal Society for Public Health in the UK says nicotine is no more harmful than caffeine. The Royal College of Physicians says there is relatively minor harm from nicotine. Look, it does contribute to dependence, but it’s much more addictive in cigarettes than these in any other form because in a cigarette smoke you get other chemicals that make it more addictive, but it has significant benefits. Nicotine and smokers use it for those benefits. So smokers enjoy their smoking because nicotine releases dopamine, which is the pleasure hormone, which makes you feel good. It has a range of functional benefits. So it improves concentration and improves short-term memory. It improves general attention, it improves weight control and it has certain therapeutic effects.

(00:13:03):

It does protect the brain from Parkinson’s disease. It improves schizophrenia, ulcerative colitis, it’s good for attention deficit disorder and smokers know this. I mean they may not be aware of the science behind, but they know that they feel better that they get benefits from nicotine. I think we should take the focus away from trying to eliminate nicotine because nicotine is relatively, but avoiding smoking, in other words, it’s the form that you take nicotine in. If you take it in with cigarette smoke, that’s what’s going to kill you because what kills people is when you burn tobacco leaves, you create over 7,000 toxic chemicals and they cause cancer and heart and lung disease, not the nicotine that does that. So if you have nicotine in vaping or in a heated tobacco product or a nicotine pouch or snooze, you’re not burning anything, you’re not getting all those chemicals. It’s not completely harmless because you are getting certain small amounts of chemicals, but there’s no comparison.

Leafbox (00:14:10):

Have you studied all the usage of nicotine in the biohacking community? There’s a very strong biohacking, people who neuro enhancement biohacking, people who are using supplements and it’s definitely like in Silicon Valley I would say if you went to the desks of Silicon Valley executive programmers, you’ll all see either snus or gum. So I’m just curious if you’ve studied how people are using or trying to eliminate those negative effects of smoking while still maintaining the positive effects and if you’ve seen,

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:14:47):

Yeah, look, it’s not something that I’ve studied. I’m not sure there’s been study it but has been part of society for over 6,000 years and there are clearly positive benefits that people enjoy. We are never going to get rid of nicotine because people are going to get positive benefits that they want. Of course there’s always some risks for everything we do and every time we choose to use a drug or form an activity, we balance the risks and the benefits and the risks from nicotine are within the risk appetite that we take every day for lots of different things. So increasingly there are people who were taking nicotine for those positive benefits. So a lot of people will say, look, when I was young I had a DHD didn’t realize I had it but I smoked and I felt much better. And then I came across, for example, vaping and I stopped smoking and I think my nicotine, the upper vaping and I can concentrate now I can think more clearly.

(00:15:40):

A lot of people use, well I dunno how many vaping increasingly people that are using nicotine for the cognitive benefits. So if you are working and you try to concentrate, nicotine knocks with concentration attention, short term memory. So it’s used for all sorts of purposes. And of course look, there are risks. It does put your blood pressure up a little, does put your pulse up a little bit. Long term, yes can lead to wound issues with wound healing. Again, minor can affect your glucose level. Again, there are small risks. Can it make you dizzy if you have too much can your headache if you have too much. But we normally use people that don’t have those problems and they get to know what’s the right dose for them. So yes, there’s a lot of that. People use T for lots of positive benefits and as long as you’re not taking it with cigarettes mode, then the risk is from that very small.

Leafbox (00:16:30):

So Colin, how did you, maybe I can explore your background a bit, but where did that neutrality towards looking at the evidence come from? Because in your latest, maybe we can talk about your retirement. It seems like your fighting entire public health industry that seems very dogmatic in resisting this conversation.

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:16:50):

There is a change, there has been a change over the years. Say we used to be much more stigmatizing smokers, smoking was regarded. It’s a bad habit that people did and they shouldn’t be doing. It wasn’t bad for them and we told them not to and they still kept doing it. They’re obviously bad people. And then increasingly we’ve become aware that it’s an addiction that people just can’t. Unfortunately there’s an association with vaping and people in who are in disadvantaged groups that stigmatized groups, prisoners, people with mental illness or there has been a stigma associated with it. But I think we have to have a bit more empathy and compassion because these are people who have used nicotine and smoking to help them with difficult lives. I think increasingly we’re becoming to see nicotine more as of the treatment for people who would struggle and to whom nicotine makes life a lot more bearable. And I think generally we are changing but there’s still a lot of stigma about, people are quite tough on because of, and there is the issue of secondhand smoke, which is a valid issue. I think people don’t want to be around smokers because of the no risk of secondhand. So I think if we avoid being exposed to secondhand smoke, we have to understand smoking is just a dependence that people developed that they would love mostly to stop and we should support ’em if we can.

Leafbox (00:18:15):

And where is this resistance coming from in Australia compared to New Zealand? I’m just trying to understand why they’re so against the vaping culture, is it ingrained tobacco companies? Maybe in your book you overview some of these forces, the taxes, maybe we can go over some of these.

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:18:32):

Yeah, look, there’s a lot of issues in Australia. I guess the main concern thing is ideological. So we’ve always had this approach in Australia that people should just quit smoking. They shouldn’t smoke evil and bad for you, we’re going to make them quit. The trouble is most people can’t. I’ve discovered that even using the best practices that we have, the vast majority quit find it very difficult to quit. And they tried and failed repeatedly the age of 40 or so. Most people this may have tried and failed at least 25, 30 times, so they won quit, but they can’t. So we have this idea that people should just quit and now we’ve got a different way of doing it, helping these people. So we recognize they can’t quit. So instead we’re going to give them the nicotine they’re addicted to but not poisons that are going to kill them.

(00:19:17):

And the Australians tobacco control movement are kind of opposed to that. Their approach always, well people should just quit. It’s like the war on drugs, you’re on drugs, you just stop. They’re bad for you. So just stop, just quit. It doesn’t work. And we haven’t quite come to terms with the idea that people are struggling. We’ve got to have our first priority is to reduce harm and for these people who are going to smoke anyway, if we can reduce their harm and reduce the risk of death, then we should do that as compassionate people and as doctors, we should reduce the risk of getting cancer, lung disease and heart disease and we can do that with safer alternatives. But in Australia we’re stuck on this abstinence only model just quickly. That’s one thing. The second thing is it’s political. We’ve kind of developed this idea that people should quit and that’s the only way of going about it.

(00:20:10):

So politicians have decided, well that’s the position which we need to take if we change that position. And because all the, in Australia, all the health organizations are opposed to safer alternatives. They just want people to quit. Then gap, there’s going to be a huge political backlash. So politicians may recognize that what they’re doing is ridiculous, that we should let people make that change. But what’s the AMA going to say, what’s the cancer council going to say? What are s going to say? These are companies or organizations that have come out against values that’s being tough on tobacco companies, which are linked to this supportive of young people who don’t want young people vaping. So we’re going to ban vaping. There’s kind of a political gain in doing nothing, in being tough on vaping. I think that’s what we’re seeing in Australia. There’s also financial issues.

(00:21:02):

We make 15 billion tax in Australian from cigarettes. We’re going to lose that if people quit smoking and it’s very cynical. But that’s a reality and it’s true in the US as well. There are vested interests. There are organizations whose reason for existence are to gain funding, to do research and advocacy against smoking to be the anti-smoking organizations. Now people quit smoking, which they will with vaping and these other S products. There’d be no purpose for, there’d be no point of having them anymore. They won’t have their conferences there, they won’t, won’t need the start. They won’t need all of the structure of their organizations anymore. So there are a vested interest. There are people who have a vested interest in the way we’ve always made people quit by just getting ’em to quit. And if we now get people to quit by a different method, that’s not the way they’ve always done it. And their legacy will be undermined by that. They’re all very bad reasons. I mean our priority should be what’s best for people in terms of public health, what’s going to prevent cancer, lung disease and heart disease, tobacco, nicotine patch will do that. But we’re not giving that those concerns.

Leafbox (00:22:23):

You see any parallels? I just keep seeing Australia had kind of, at least in the US, a negative image during Covid for a very strict authoritarian approach to the Covid pandemic. I’m just curious if you see parallels there. It just seems like public health in Australia is very authoritarian.

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:22:41):

Absolutely. I think there’s a real issue about Australia being a nanny state and we know what’s best for you and we’re going to sell you what to do and then we’re going to make you do it. In New Zealand, they’re much more progressive. I think that’s why we’re, they’re seeing a big difference certainly across the, in New Zealand, the hard principle John Mills has developed something years ago. I think it’s something we should be living by but we’re not. And that’s all about the government has no role in changing people’s behavior if what they’re doing is harming, no one else. So if you want to vape and that’s your business and you’re not hurting anyone else, none of that is the government’s business. And I think America is more that view in Australia. We think we have this right, the government has the right to tell people what to do, what they’re doing is not harming anyone else. If it’s harming someone else, it’s pretty relevant, but it’s not what you do in the privacy of your own life, in your own home or even outside. If it’s not someone, it’s not their business.

Leafbox (00:23:43):

And where do you think their psychology comes because you’re describing more of a libertarian attitude, the US libertarian kind of, I don’t know enough about Australia’s mental state, but it’s almost a conservative argument to let people do what they want at home, right? Smoking in a way is a conservative thing, right? If people want to vape in their own home, that seems like a conservative argument. So if these public health organizations in Australia are authoritative, like you said the nanny state,

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:24:13):

It’s authoritarian. Absolutely. Look, there are libertarian groups in Australia and some of them are fighting for vaping and other personal rights. So there are a range of views, but I think the dominant view is authoritarian that the government has gone too far. I think we’re talking about government overreach here in many areas. There are many areas. In fact there was in one of the states we had a review, a nanny state review, which they looked at all those sorts of issues where the government was overreaching, maybe certainly one of them. I dunno if there’s any question about that. It’s a human rights issue. It’s a social justice issue and people have a right to choose a safer alternative. If you’re smoking and you can’t quit, you have a right to choose a safer alternative. It’s wrong for the government say no, you have to keep smoking or stop. Well, I can’t stop so I have to keep smoking. That’s wrong. It’s a human rights issue because people who smoke increasingly concentrated in disadvantaged groups, we should be helping them not making it up for they’re already struggling as it is. We’re telling them that they have to do it that way, which isn’t working for them.

Leafbox (00:25:23):

Could you give me a context just for listeners to know, so currently you need a prescription to get I guess a vape license. How does that work? What are the practicalities of it? How does that differ to other countries? Look,

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:25:36):

We’re the only country in the western world that has the requirement to have a prescription for nicotine to vape and possess nicotine legally. So if you want to legally vape, you need to find the doctor who writes script for you and very few will for lots of reasons which we can talk about. Then you have to go to a pharmacy, you have to find one that will prescribe, that will dispense vapes and very few do, and you have to find one that will dispense the ones that you’re interested in. Currently you can with that script import nicotine overseas, but from the 1st of March, the government’s going to ban the import scheme. So people will have to find a doctor, find a pharmacy, and buy a product that’s available. Now that’s an absurd situation when you can go to the corner shop next door and buy a pack of cigarettes that you know are going to kill you.

(00:26:28):

So we’re telling people, yes, you can buy cigarettes anywhere up to 40,000 outlets in Australia, but you want to get a much safer alternative. You have to jump through all these hoops. Now clearly that’s stupid and people have recognized that and over 90% of people who vape in Australia and there’s 1.7 million adult vapers don’t have a prescription. So they vape illegally. What do they do? They buy them from the black market. So the black market has said, well, no one’s going do that and people aren’t so we’ll provide them for you. So that’s now thousands of outlets. They’re providing unregulated products that are imported from China that are controlled by criminal networks and solved freely to young people that pay no tax that are providing these products to anything who wants them. We’ve set this up as a way of trying to regulate things. We’ve ended up with the biggest possible mess and enforcement’s making no difference. And that’s something we’ve seen with other drug wars in the past. When you’re trying to force these kinds of restrictions on drugs, they don’t go away. If people want them, they find another way to get them. And black market will step up, provide by created ways to make those products available and that’s what they’re doing in Australia.

Leafbox (00:27:47):

What percentage of the vapers are actually getting the legal e-cigarettes? I’m just curious.

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:27:52):

7% have a seven to 8%.

Leafbox (00:27:55):

You’ve created a million and a half criminals.

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:28:00):

So we’ve criminalized other people who would normally be law abiding who want to do the right thing, who are trying to improve their health. We’ve criminalized them and we going to and we’re cracking down on them where there’s increasing enforcement and we don’t actually experience law enforcement or drug crime doesn’t work. It doesn’t reduce the amount of drugs supplied. It doesn’t reduce the amount used. We’ve seen that over and over again. We banned heroin in Australia in 1953. The survey last year from the local university found that over 90% of heroin drug drug use said it was easy or very easy to get heroin. It just doesn’t work. Little bit prohibition in the US it just didn’t work. It created criminal organized crime, stepped up bootlegging moonshine, we saw all the complications to help as a result. Sure alcohol intake dropped temporarily. Well, it was a disaster in the end. They couldn’t control it and they ended up reviewing alcohol and changing the laws and that’s what’s going to happen in Australia.

Leafbox (00:29:16):

Is this the same thing for other like SNUS products or gums or lozenges or sprays? Are those regulated as well or totally illegal In Australia?

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:29:26):

In Australia basically essentially their banned people point view. You can jump through hoops if you define the doctor, they’ll do this for you filling forms and you get customs forms and you pay taxes. But from a practical point of view, they’re all bad, which again makes no sense. The government I think is very attached to its tobacco tax, which is our fourth biggest tax or now the fifth biggest tax in Australia. And they’re clearly concerned about losing that tax. I can’t say. What I can say is that most people believe that’s the case.

Leafbox (00:30:05):

What is a pack of cigarettes cost in Australia for people to know

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:30:08):

In Australia? Yeah, Australia has the highest cigarette prices in the world. Again, it’s not a big mistake we’ve made. We’ve put the prices up so high, it’s got to the point where it’s not making any difference whatsoever that we’ve gone past the point of diminishing returns where people get addicted, they just have to keep smoking. And we’re talking about disadvantaged people who are becoming financially disadvantaged further by this. Now in Australia for a pack of borough, you might pay over $40 paid 20. In the US I think it’s 12 or $13. It’s by far the highest anywhere in the world.

Leafbox (00:30:44):

So what’s the role of the black market in the tobacco sales? Is there one?

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:30:49):

Yeah, so huge. So the back market now because of these high prices is about 25% of the total market for the tobacco in Australia. So the government’s losing 4 billion a year in tax organized crime and stepped it up. And we have all the problems now that go with organized crime and gang wars gangs. There are turf wars to control the market tobaccos to being fireball there murder because of these turf wars, there’s extortion. These organized crime groups go into a tobacco shop and say, you sell our illegal product. They say no. The next night their shops bomb. There’ve been over 50 tobacco. That’s fire bomb in the last 12 months. And that’s just starting and it’s building up. It’s an absolute disaster. It’s a total mess we’ve made. I mean we all understand that you need to increase taxes and make the more expensive and that’s good to a point because it discourages people from smoking. But after certain point it becomes powerful and we’ve gone way past that point. In Australia, people who are disadvantaged up, been financially home, we’ve created a huge criminal network, we’re not getting the taxes, it’s just a disaster. It’s a warming to other countries. There’s a point where you have to stop and stop being greedy.

Leafbox (00:32:12):

Do you apply the same harm reduction model towards all drugs, do you think? I mean, where do you fit on the paradigm?

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:32:21):

Look, I don’t think it’s any different. I think what we’re doing with tobacco harm reduction, it’s the same as all the other forms of harm reduction. I’m talking about pill testing, medically supervised, injecting rooms, condoms to prevent AIDS, seat belts to prevent car accidents . It’s all about accepting that there are certain things people are going to do whether you like it or not. We don’t say to people, look, you can’t drive your car because people keep getting killed on the roads. We say, look, drive your car, but just wear your seatbelt and now the car’s going to have airbags as well. So it’s recognizing that people take risks and they may measure risks, they make their own minds up. They do what they want to do. But our job in public health is to protect them, to save lives and protect them from injury. And this is no different.

(00:33:13):

Tobacco harm reduction is no different. The difference is that tobacco kills more people than all other drugs, all car accidents, suicides, HIV, and a whole range of other harmful behaviors than all of those together. I mean this is the big one. And yet in Australia and in certain countries it’s opposed. They support and that’s the irony. Australia theory supports hub reduction, but when it comes to tobacco hub reduction, which is killing 21,000 people, far more than anything else, oh no, we don’t want that because kids might use these products or because we don’t know the long-term risks. Okay, we know that two out of three people are going to die from smoking and we know that vaping is much, much less hard. But we dunno exactly two decimal points what’s going to happen in four years time. So we’re not taking any chance. It doesn’t make any sense.

Leafbox (00:34:07):

And do you think that just keeps coming from the demonization of the tobacco companies and then association with the tobacco products?

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:34:14):

Well, yes. I think part of the problem in Australia is that we’ve had this big struggle with tobacco companies. So over the years we have introduced various forms of legislation, various rules to restrict their activities. Now tobacco companies always fought against that. There’s been lots of legal action and I think the tobacco control experts have had very bitter and hostile interactions with tobacco companies. Now that we have an alternative to smoking, which the tobacco companies have started to engage with. The argument is well, that the tobacco companies are involved with is it must be bad, there must be some evil sinister plant. This must be a conspiracy by the tobacco companies to hook young kids to vaping or to nicotine. Now that’s absolute nonsense because the tobacco company don’t want vaping pouches. They want people to buy combustible cigarettes that is the most profitable consumer product ever invented, but they’ve got no choice. If they don’t get involved like Kodak, they’ll go under, this is their Kodak moment. So now about 12% of the world’s e-cigarette market is controlled by the tobacco numbers. So that is because of that association. Tobacco Control Australia and in some other countries said, well, this must be an evil tobacco conspiracy, so we going to oppose it. Whereas in fact what they’re doing is they’re supporting the tobacco industry because vaping and cigarettes are substitute. If you stop vaping, people will smoke more. That’s how stupid this is that they’re actually supporting the cigarette industry and there are more cigarettes sold because of that opposition.

Leafbox (00:36:08):

Do you have any thoughts on the flavor additives and things like that? In many countries in the west, in the US there’s a lot of legislation against bubble gum or Coca-Cola flavors and they always try to come up with these restrictions because of the kids. So I’m curious where you stand on that or your thoughts or what the situation is in Australia.

Dr. Colin Mendelsohn (00:36:27):